My grandfather spent his working life as a fireman on the railways and my father, having grown up living next to a busy railway line, was a big railway enthusiast so it’s perhaps not surprising that railways featured heavily in the young Arthur Dent’s childhood. Family holidays tended always to be planned around visits to the preserved railways of Cumberland, Lancashire, Yorkshire or Wales; at home, attics were floored and a series of extensions were built to accommodate Mr Dent senior’s ever-growing model railway collection, and we spent many a weekend going to model railway exhibitions, swapmeets and model shops. My first Saturday job involved working in a model shop (the shrewd owner knowing I would almost certainly spend my modest wage on another wagon or coach from his shop). When we were older, the Dent siblings volunteered on preserved railways.

Alongside my interest in railways, when I was about nine or ten when most normal kids were outside playing football or fighting each other or collecting Panini football cards or riding their Raleigh Chopper, I developed an interest in maps. I’m sure you will remember when you were a nipper constantly being asked what you wanted to be when you grew up, to the extent it became irritating. Well, my answer of “cartographer” was a perfect response because many grown-ups didn’t know what one of those was but also didn’t want to admit it, so that tended to cut the conversation short. And also, I was genuinely interested in maps. Well, looking at them at least, I’m not sure I had the first idea how cartographers made them.

These two interests – railways and maps – combined with the long boring winters those of us who grew up in small town 1970s Scotland had to endure, led to me becoming fascinated with tracing the routes of old railway lines on the 1:50,000 (or one inch to a mile for you oldies) Ordnance Survey maps I started collecting. And, when we “went out for a run in the car” as people used to do in the 1970s when “motoring” was seen as a pastime in its own right, I would always look out for signs of disused railways – perhaps signs of a part demolished railway bridge, an old embankment or cutting or a tunnel entrance. I was too young to put the feeling into words back then but I think somehow I felt the sadness of something lost and also the curiosity of what life might have been like when steam railways criss-crossed the country (I was born almost exactly at the end of the steam era in the UK).

Fast forward about 25 years and, having departed Scotland for the bright lights of the south of England but with family still north of the border, long boring road journeys “home” became a regular feature of my life. In particular, trips up the A1 to Scotch Corner and over the A66 to Penrith were a frequent occurrence. After the long boring motorway driving up the A1 through generally flat countryside, suddenly the terrain gets a lot more interesting as you turn off and start heading West. The traffic (bank holidays apart) also thins out and it’s safe-ish to look around at the landscape, which changes from lush farmland to increasingly barren moorland as the road climbs across the Pennines. One feature of the scenery which didn’t escape the eagle-eyed Dent as the A66 reached its summit at Stainmore was all the tell-tale signs of a former railway line. Why on earth was there a railway here? How did they build it over such difficult terrain? Which places did it connect? When was the track removed? Is any of the line still in existence? Could it ever be reinstated?

All of these questions and more led me to start doing a bit of research and, on one of those many journeys North, to finally turn off the A66, explore some of the beautiful countryside and try to trace the route of the old railway a little more closely.

This article describes what I found out. The first part will cover a brief history of the line and the route. Future parts will talk about the line during its operation and closure, the state of the line today and efforts to reinstate parts of it.

I know there a few Puffins who live in or hail from this area and are probably much more familiar with this railway than I am, so hopefully they can fill in the inevitable gaps and correct any errors in the comments no-one reads.

The Stainmore Railway – a brief history

As an example of the explosion of enterprise and vision of the 1840s and 1850s railway industry, numerous different schemes were proposed to cross the Pennines from various different start and end points and connect what are now the East Coast and West Coast main lines. Three such proposals came together under the auspices of the Northern Counties Union Railway. However, some intervention by the Duke of Cleveland over the cost of crossing his estate between Bishop Auckland and Barnard Castle (long before it became famous as the UK’s premier eyesight testing centre) ultimately caused this scheme to founder.

However, a new scheme to connect Darlington and Barnard Castle which bypassed the Duke of Cleveland’s estate was proposed and ultimately given consent in 1854. Building work started immediately and the line opened in 1856. There were stations on the line at Piercebridge, Gainford, Winston and Broomielaw.

This enabled the construction of the remainder of the East-West route, and construction of the Stainmore Railway by the South Durham & Lancashire Union Railway began in 1857, with the line opening to passengers and freight in 1861. It initially consisted of a single line between Barnard Castle and the northbound Lancaster and Carlisle Railway (now the West Coast Main Line) at Tebay, a name familiar to anyone who has travelled up and down the M6 and stopped at the eponymous service area. A southbound junction was later added.

The answer to the question “why on earth did they build a railway here?” is, as is usually the case, to transport valuable freight. In this case minerals – Durham coke to furnaces in Cumberland and iron ore back to Cleveland.

Mergers and takeovers were already a thing in the railway industry of the 1860s, and the SD&LUR soon became part of the North Eastern Railway, which ultimately formed part of the London and North Eastern Railway, one of the Big Four railway companies formed in the grouping of 1923.

In addition to the route from Barnard Castle to Tebay via Kirkby Stephen, a second branch (known as the Eden Valley Railway) was built, from Kirkby Stephen via Appleby to the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway main line near Penrith, opening a year after the Stainmore section. Initially this line connected to the southbound Carlisle to Lancaster main line, but lines were later built to connect it both to the northbound main line and also to the now-dismantled line from Penrith via Keswick to the West Cumberland coast.

By 1874 most of the route had been converted to double track to increase capacity, allowing for ultimately twenty mineral trains per day to travel along it. In addition to the mineral traffic for which it had primarily been built, for much of its life the line supported five passenger services per day and also summer holiday excursions transporting people from the North-east to and from the Lancashire holiday resorts.

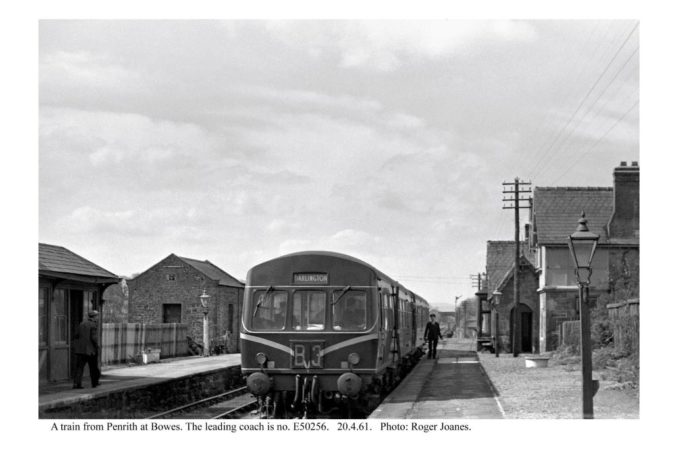

Following the nationalisation of the railways in 1948, however, signs that the line may not be ultimately be financially viable began to appear. Several stations on the Kirkby Stephen to Appleby section were closed in the 1950s and passenger services on the Tebay branch reduced. By December 1959 (even before the infamous Dr Beeching had started taking his scalpel to the British rail network) a proposal had been made to close sections of the line.

Despite petitions by local people, and despite the introduction of faster – and cheaper to operate – diesel multiple units for passenger trains on the route, the Government confirmed in December 1961 that the vast majority of the line was to be closed, and the last passenger train operated on the route in January 1962. The Eden Valley line remained open for quarry traffic as far as Hartley until 1974, at which point the track was lifted back as far as Warcop. The Appleby to Warcop line remained in occasional use for army traffic until 1989 when the line was closed, although the track on this section remains.

The level of passenger traffic on this route was never sufficient to make the line profitable on its own (particularly given the numerous viaducts to be maintained on the route and the toll the harsh winter weather would take on the track and equipment) and as goods traffic diminished, closure was perhaps inevitable in retrospect, however sad it was for the many who campaigned against it.

Route

The Stainmore Railway is generally used to describe the line between Darlington and Tebay and Eden Valley Railway to describe the line between Kirkby Stephen and Clifton via Appleby. The two lines are shown in blue in the map below. The Lancaster and Carlisle Railway line (now the West Coast Main line) is shown in purple and the Midland Railway’s Settle to Carlisle line is in yellow

Darlington

The route across Stainmore began at Darlington North Road station. Trains headed North on the Bishop Auckland line for a short distance and then turned West out of Darlington to follow the North bank of the River Tees. Piercebridge station was the first stop, followed by Gainford. After Gainford the line crossed the Tees by a viaduct, the first of many on this line, and then turned North-West and crossed back again to the North bank.

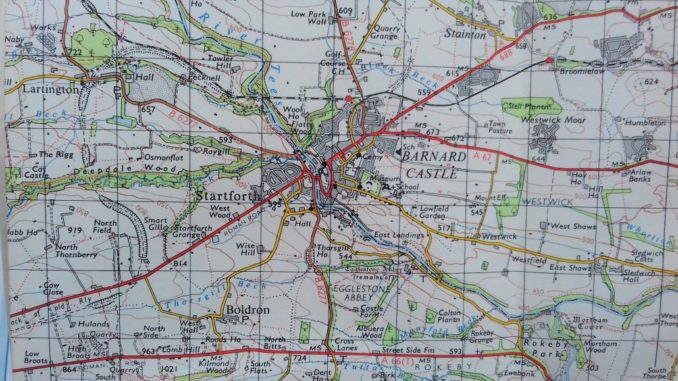

Resuming its Westerly course, Winston station was the next stop, followed by Broomielaw. The line then arrived in Barnard Castle, with the line from Bishop Auckland joining it from the right just short of Barnard Castle station in the 1964 map below.

Barnard Castle

A new station was built specifically for the SD&LUR at Barnard Castle, and this ultimately replaced the existing station as the town’s main station.

From Barnard Castle the line then ran West, crossing a high viaduct over the River Tees.

Uncredited photograph published in Tomlinson as above with the line From a photograph taken about 1858. Most of the images in Tomlinson are credited with authors., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It then curved southwards towards Lartington, leaving behind the former branch line to Middleton-in Teesdale. Passing under what is now the A67 Barnard Castle to Bowes road it then resumed a Westerly direction passing across farmland until it reached Bowes.

Bowes

From Bowes the line continued West, its trackbed occupying land which today forms the A66 dual carriageway, and then followed the bank of the River Greta up gradients of up to 1 in 67, posing a challenge for the drivers, or more correctly, the firemen, of the heavy mineral trains using the route. The terrain gradually turned from farmland to desolate moorland as the line reached the Stainmore summit at 1370 feet, marked today by a replica of the sign which previously stood on the spot. There was never a station here but trains did halt here to drop off and pick up railway workers who lived in the cottages next to the line (later demolished when the A66 road was widened).

Stainmore

Hugging the contours of the hills to minimise gradients, the line then curved round to the South to Barras, site of another former station, at one time the highest railway station in England. Continuing south, the railway engineers were now confronted with a significant challenge – the 457 yard wide and 200 feet deep valley of the River Belah.

Belah Viaduct

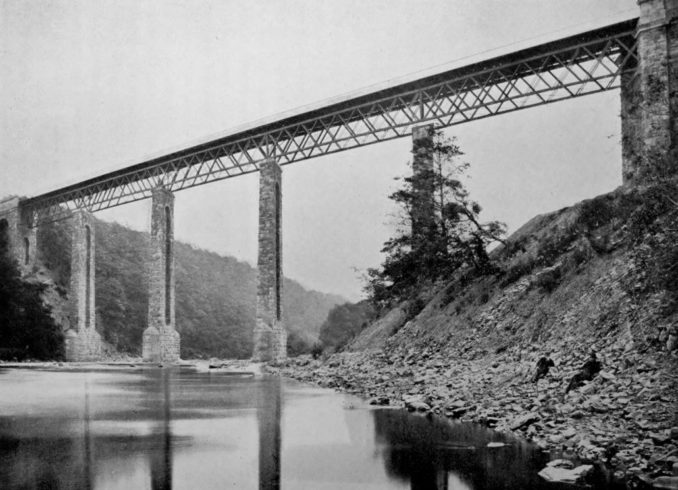

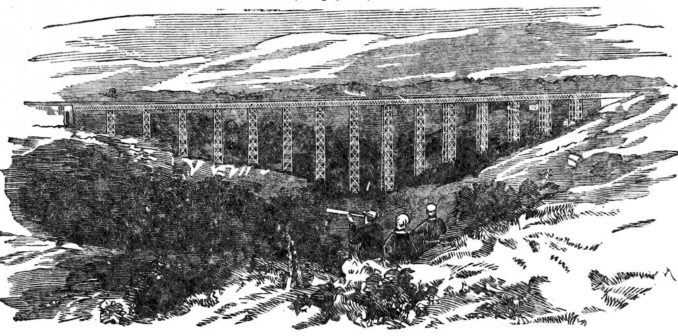

Despite the best efforts of Thomas Bouch on behalf of the somewhat cash-starved SD&LU Railway to engineer an economical route, there was inevitably a need to bridge numerous rivers and valleys on the journey from Darlington to Tebay. Twelve different viaducts and numerous smaller bridges were the result, many of which were very striking structures and some of which survive to this day.

But the most impressive of all was the wrought iron structure built to bridge the River Belah South-west of Stainmore summit. At the time it was the highest bridge in England at 196 feet high. It was 347 yards long with 16 spans. Construction work started in November 1857 and finished just two years later, remarkable progress given the inaccessibility of the location and the relative novelty of the construction.

The viaduct’s design and the inconsistent maintenance which was applied to it over the years meant that there were restrictions imposed on trains using it. Only engines with relatively light axle weights could be used. This was a problem since the mineral trains being hauled on this route were long and heavy and also the inclines of 1 in 60 or 1 in 70 demanded significant power. The solution was the use of two light engines, either by double heading or having one banking engine push from the rear. Trains would also sometimes be split for the descent from the summit at Stainmore.

BRAITHWAITE, John W. Shelfmark: “British Library HMNTS 10351.cc.34.”, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

There was a signal box a short distance from the viaduct on the Western side, which employed three signalmen and was open round the clock. The structure survives to this day, albeit in a derelict state.

The viaduct served the railway and its passengers for 102 years (outlasting by some distance another Thomas Bouch design, the first bridge over the River Tay in Dundee which collapsed while a train was crossing it during a storm in 1879).

However following the closure of the line in January 1962, work on removing Belah Viaduct began immediately with its wrought iron all sold for scrap. Within a year the entire structure had gone. While it would be hard to argue that the line as a whole might remain viable financially, the destruction of such a remarkable piece of engineering, and history, seems sad in retrospect.

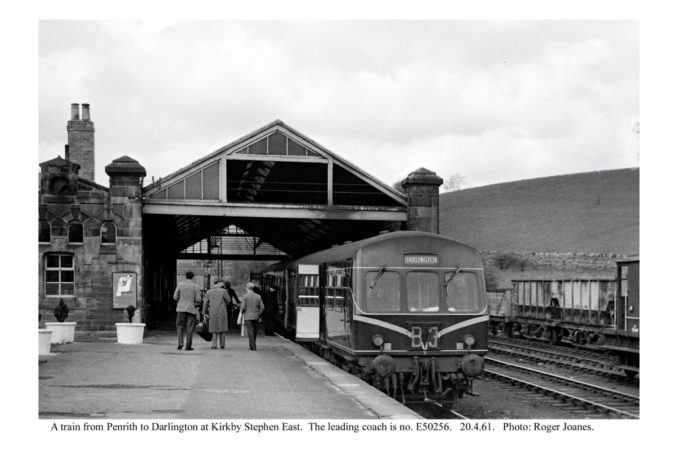

Having crossed the Belah, the line then curved round to resume a Westerly course, crossing Redgategill Viaduct, passed through more farmland and headed South-west across Merrygill and Podgill Viaducts and passing Hartley Quarry before finally swinging West to arrive at Kirkby Stephen East railway station.

Tebay Branch

West of Kirkby Stephen East station the line divided with the Tebay branch continuing West. There was, for a while, a station at Smardale serving the nearby Smardale Hall and a few isolated farms. The line then passed under today’s Settle and Carlisle line near the magnificent Smardale viaduct and then turned south to follow the bank of intriguingly named Scandal Beck before crossing the valley via another magnificent construction which survives today – Smardale Gill Viaduct.

From here the line followed the River Lune all the way to Tebay, the trackbed forming the foundation of what is today the A685 road, passing through stations at Ravenstondale and Gaisgill before joining the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway (now the West Coast main line) near Tebay station, and journey’s end for us (and for most passenger trains, although holiday specials and mineral trains would have continued South from here).

Eden Valley Railway

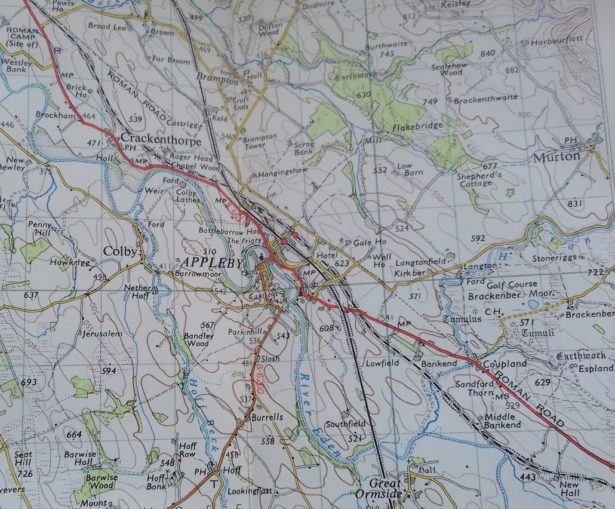

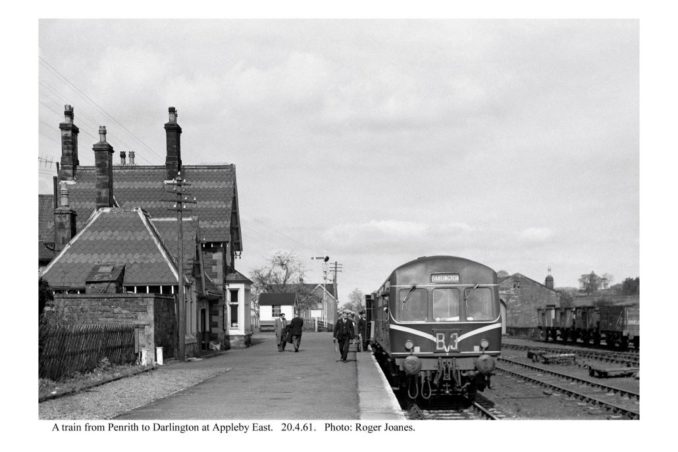

After leaving Kirkby Stephen East, after the Tebay line branched off to the West, the Eden Valley line continued North through open farmland, crossing Scandal Beck and the River Eden before reaching the station at Musgrave. Continuing North-west, the line called at Warcop station, headed along the North bank of the River Eden, crossing Coupland Beck by a viaduct. Two miles later the line arrived at Appleby East station. Appleby was also served by the Settle and Carlisle line and by another station which is still in use today. The two stations can be seen side by side in the 1955 map below.

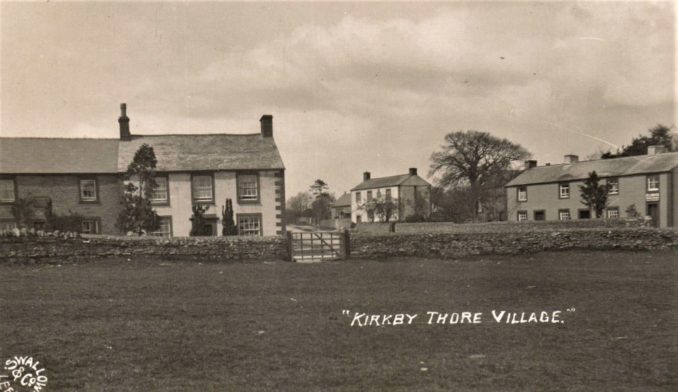

After Appleby, the line passed under the Settle and Carlisle line (to which it was later connected) and turned first West, on the line of what is now the A66 Appleby bypass, and then North-West, passing the village of Crackenthorpe, before again joining the line of today’s A66 as far as Kirkby Thore station.

Turning West again, after another mile the line reached Temple Sowerby station and then crossed the River Eden again at Skygarth viaduct. Next station was Cliburn after which the line continued Westwards for a few miles before turning south to join the Lancaster to Carlisle main line at Clifton station (subsequently renamed “Clifton and Lowther”.

A junction and new line were later built to the North to join the Northbound main line just south of Penrith station, and a new station (initially also called “Clifton” but later renamed “Clifton Moor”) was built. This station featured a private waiting room for the Earl of Lonsdale (I can imagine the local proletariat would have loved that). The Northbound junction was much more practical for operations than the southbound one, allowing through trains to Penrith, Keswick and onwards to West Cumbria, and the southbound line and station were quickly closed and the track removed. The two stations can be seen in the 1955 map above (far left).

So that was the route. The distance from Barnard Castle to Tebay was only 35 miles but what the Stainmore Railway lacked in length (filth!) it made up for in the epic nature of the terrain, the weather conditions to be withstood, and some of the engineering involved.

In the next part of this article I’ll talk about the line and the people and locomotives that worked on it during its years of operation.

References

http://www.cumbria-railways.co.uk/stainmore_history.html

http://www.cumbria-railways.co.uk/diesel_trip_over_stainmore_1958.pdf

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KXObLbUn2gc – DMU travels from Barnard Castle to Penrith over the Stainmore route.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s6GRF8MnUgw – The Stainmore Railway and Belah Viaduct

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bM3lA5LYNRQ – The Highest Railway in England

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ugIoMD495E – Snowdrift at Bleath Gill. Story of a freight train trapped in a snowdrift on the Stainmore Railway.

http://www.forgottenrelics.co.uk/bridges/belah.html

https://www.stainmore150.co.uk/

© realarthurdent 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file