James Gillray, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Regency Britain by Ian Mortimer. Publisher The Bodley Head

This is the latest in a series of Time Traveller’s Guides by Historian Ian Mortimer and his enthusiasm for his subject shines from every page. The author gallops through thickets of facts and anecdotes with the reader riding pillion, hanging on for dear life. Occasionally we might fall off, but that’s okay, as each chapter has a useful heading such as The People, What to Wear, Cleanliness, Health and Medicine and many more, so it’s easy to climb back on again.

Characters, both known and unknown by us, pop up like Whack a Mole: Telford, George 111, Sheridan, Sheraton and a group of Regency transvestites for your delectation. There were lots of others including one Ann Lister, lesbian of her parish, who is mentioned no less than 27 times. She has recently had a TV drama made about her, so I suppose there was a lot of information about her life. I thought she seemed a cruel bitch as she whipped her horse ‘worse than the day before’, for being knackered after a 30 mile ride, and the following month had him stabbed in the heart. It took the poor beast 5 minutes to die. I recognise 200 years ago sensibilities were different, but if we can denounce them by our moral standards regarding slavery, we can do so with animal cruelty, no?

My favourite character apart from the poor lady language teacher incarcerated in a lunatic asylum, was a little Devonshire boy, a prodigy with a computer for a brain, who could answer mental maths questions within seconds. He was so unusual he was taken to the court of Queen Charlotte at the age of nine and asked the following by her:

‘From the Lands End, Cornwall to Farret’s Head, Scotland, is found by measurement to be 838 miles. How long would it take a snail creeping at this distance at the rate of 8 feet per day?’

He replied after a lengthy 28 seconds, ‘553,080 days’.

Far from being a savant whose genius ebbs away in his twenties, he goes on to work with the Stephenson brothers laying out the railways, becomes co-founder of the first electric telegraph company, oversees the building of the London Docks and eventually ends up as President of the Institution of Civil Engineers. Game, set and match.

Telford also did well for a working class lad from a poverty stricken, single parent family, building all but one of the bridges across the Thames in London (at that time). Mr Mortimer is very impressed with the feats of building and engineering in the Regency, as am I, but I suppose many of these innovators, designers and builders, weren’t quite as hampered by planning rules, committees and so on, nor perhaps by formal education as they were mostly self-taught.

The book is PC, no doubt about it, but the ‘correctness’ is more the horse’s back end rather than its bridle, so don’t let it put you off.

What surprised me was the similarities between then and now, not the differences. The French Revolution had happened so there was much unrest here: poverty and unemployment caused by the Corn Laws and military men coming home to no jobs and no pay, but in the end the English didn’t copy the French and bump off the elite. According to Mortimer they had seen the Terror years in France and thought ‘best not’. Also the author thinks the shape of England didn’t help the marchers who were protesting from the North, being long and thin (England not the marchers). Interesting hypothesis.

Another rather sad similarity I thought, was that between the ‘care’ for inmates in the lunatic asylums, and that of our elderly in ‘Care homes’. In early Regency days these poor people were often treated very badly indeed being abused and sometimes starved . Their relatives often paid huge sums for their upkeep and unscrupulous asylum owners milked them as cash cows. When I saw some recent pictures of elderly dementia patients who looked half starved in today’s care homes, I thought ‘so what’s changed then?’

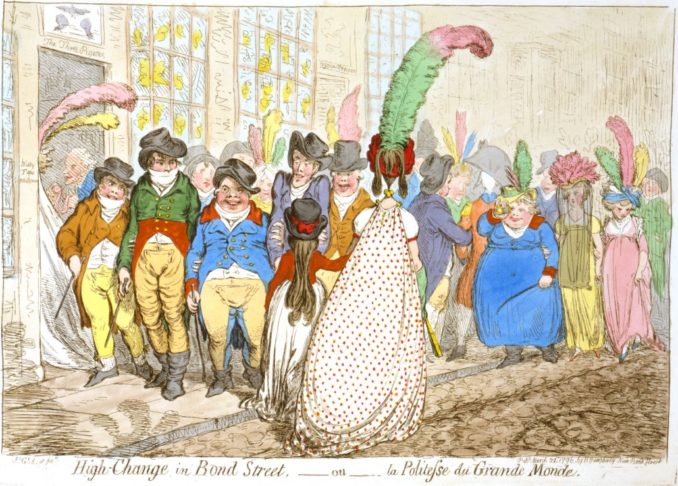

Where the book came unstuck, for me personally, was the omission of info. in the fashion chapters. Maybe Mortimer wasn’t that interested in that topic? George ‘Beau’ Brummell and his wonderful tailoring got a mention, but not the daft fashion amongst the girls for wetting their muslin frocks to make them more clingy and revealing. Of course many of them got pneumonia. Serves them right.

Racism has its own section and slavery is mentioned with some examples which are unpleasant. Later the author tells us about the appalling conditions in the mills and mines, telling of four year olds going down into the mines to look after their parent’s food supplies. I suppose the parents felt they were safer there than being left at home unattended. I expect if you asked a four year old of the day, spending 12 or 14 hours in the semi dark breathing foul air, whether they would swap a life with a cotton picking slave child in the US, I am pretty sure what the answer would be. One could say ‘well they had a choice’ but they didn’t really did they? They were effectively slaves to the mine owners. It wasn’t really about colour here in England, but class and poverty. Probably still is.

Mr. Mortimer sub-divides many of his chapters by class…a useful tool, as we get a better impression of how each group differed. Aristos?…wealthy and sometimes profligate; middles and upper middles?…apparently did most of the inventing, innovating, changing, building…how wonderful that some of them had servants to pick up the slack; working class? …well, a bit smelly living in all those hovels and on subsistence rations.

To be fair we were given occasional glimpses into the real hardships of working class life: for example: the groups of girls who walked the 160 miles to London every year for seasonal work carrying produce from markets, often another 11 miles a day or more with heavy goods on their heads. The working class and of course the underclass mainly don’t seem to have done anything of importance except to be a bit of a nuisance, but maybe that’s because a lot of them were illiterate, couldn’t write about their lives, and were probably just as knackered as Ann Lister’s horse; working their butts off so their ‘betters’ could function. It took writers like Dickens and Hardy to write about the hardships of working lives…perhaps because they themselves had experienced it?

Ian Mortimer gives us an exciting ride through the Regency and one can only admire his diligent research and plethora of information’ and above all his enthusiasm. However, before I was halfway through the book, I was longing for all these facts, anecdotes and wonderful characters to be woven into a story, a racy, pithy novel maybe. Where is the Jane Austen of today who could do this for us?

This is a book very much to be recommended, but perhaps best read in small bites. Thank you so much Mr. Mortimer for the distraction from present day problems.

© Wattylers wife March 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player