In earlier parts of my story I described in general terms why and how I started educating myself about sailing and the main technical things to look out for in a yacht’s design and specification.

In my case the principal criteria governing these choices were that the yacht had to be capable of long distance cruising, it had to be manageable single-handed if necessary, and its price had to be within a budget set mainly by the cash I could raise by selling my house and contents in Northumberland.

The Swedish “Windscreen Cruisers” made by Hallborg-Rassy, Malo and Najad were so-described because they all had fixed screens around the cockpit to protect the helmsman and crew from wind and spray. They were very well made in high quality fibre-glass with attractive-looking teak decks and fine internal cabins mostly finished in mahogany, walnut, or rosewood. The British-made Rustlers and Vancouvers were highly viable contenders too with both having a good reputation as strong seaworthy boats. I boarded examples of them all at the Southampton Boat Show in the autumn of 1995. At the same Show I also came across two other craft exhibited by UK Agents of their United States builders – Island Packet and Pacific Seacraft.

Any one of these would probably have been a good choice but I had to narrow options down to a single model if I was to keep to my self-imposed time-table of taking delivery in 1996 and starting this new phase of my life as soon as possible.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

All the makers had different models in their product range, typically 32-34 feet Length Overall (LOA) in the smaller size and 36-38 feet in the larger. But their Waterline Length (LWL) varied considerably, as did their underwater body-shape, and as explained in earlier articles those characteristics are extremely important because they govern the balance struck by the designer between speed, safety, comfort and maneuverability.

I attached priority to sea-worthiness and sea-kindliness over speed and accommodation and on those grounds eliminated the smaller of the Swedish models and worried I couldn’t afford the larger ones, though after looking at them all I would have dearly loved a Najad 36.

The Rustlers were “long-keel” boats giving them great directional stability but that made them harder to maneuver through tight turns in close quarters and when changing direction at sea.

The Vancouvers, my initially preferred design based on reading alone, turned out to be extended versions of a 32 feet design. The cockpit and stern had been lengthened to increase speed, cockpit size and external locker space but lost some of their appeal as the cabins and forward part of the boats remained unchanged.

The Island Packet was a high quality product but again with a long-keel and high topsides designed to increase internal accommodation but for that same reason having more ‘windage’ and consequently being more inclined to suffer from leeway (being blown sideways to the desired direction of travel) – furthermore, I didn’t like the high-pressure sales-tactics of the UK Agent at the time.

So, my short-list after the boat show ended were to go for either a 34 foot Vancouver or one of the Pacific Seacraft models, and I entered into intensive discussions with both builders during visits to their factories.

Travel to the British Builder was easy as they were based in central southern England.

Pacific Seacraft were of course more distant but I had enough air-miles left from my employed-life to make a return flight to Los Angeles to visit their factory at Fullerton – the business was later bought by a father and son who moved it lock, stock and barrel, including many of the key workers and machines to North Carolina where it still builds and services the same types of yacht.

COMMERCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

During the Boat Show I was cautious about the form of contract I would need to enter into and there I came across a potential snag with British Makers. They were members of the trade-body – British Marine Industries Federation (BMIF).

As Adam Smith wrote in the “Wealth of Nations”, in 1776 – “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public ….”.

The member firms of the BMIF I was considering required terms of payment whereby the purchaser effectively financed the costs of production by making stage payments before completion. Other firms using the same business approach had gone bankrupt not long before and I was concerned about what might happen if the firm I chose went bust before my boat was handed over – would I get my money back? – or would I end up as an unsecured creditor of a failed business?

In response to my queries the Swedish builders had an answer – they would provide an Irrevocable Banker’s Guarantee in exchange for an additional few per cent on the price – that meant I could recover progress payments from the bank if the builders failed to deliver a completed yacht (in other words the risk of contractual default through failure to deliver was transferred from the builder to the bank who no doubt demanded payment and guarantees of their own from the builder).

In Post-Boat-Show discussions the short-listed British Builder was very reluctant to do that and only at the very end offered a semi-guarantee by a Trust whose Trustees were also Directors of the Yacht-Building Company itself. I didn’t investigate whether the Trust was backed by sufficient Assets to be able to honour the guarantee it would provide, but the firm’s reluctance and this two-hatted approach created doubts in my mind about the financial security of the business.

Pacific Seacraft, based near Los Angeles at the time, in whose factory I spent a week crawling through partially completed yachts, including both the Crealock 34 and 37 models couldn’t have been more helpful in providing access, explaining issues, and agreeing special customisation of their standard product as priced extras in daily discussions with me.

By this time I had worked out that the costs of yacht ownership increase steeply with overall length. New and maintenance hull costs increase roughly in proportion to the cube of length, mooring costs in proportion to length, and so on. I reckoned a very rough guide was that a 37 foot long boat would cost about 25 % more than a similarly equipped 34 foot one and that within my budget I could afford a very basically equipped 37 or a comprehensively equipped 34.

Pacific Seacraft also understood my commercial concerns and we ended up agreeing terms of payment that made an Irrevocable Bank Guarantee unnecessary. Essentially these were that I would make a non-refundable down-payment with order to give them confidence I would keep to my side of the bargain.

In return the balance of price would be payable after delivery of the yacht to their agent in Falmouth and handover to me with a later small value payment retained as security against the need to make good any specification shortcomings.

Being satisfied with both the technical and commercial aspects of the Pacific Seacraft offer I decided to buy a Crealock 34.

In passing, I note that this experience of a competitive and customer-friendly attitude contrasted markedly with those of the larger US Corporations with whom I had dealings during my employed life. They very much adopted the attitude – our business is technically, commercially and managerially optimised to provide a high-quality standard product and we are unwilling to change our offer to suit individual customers.

I’ve no idea whether Pacific Seacraft are now equally responsive, though they served me well with support and parts later on, sometimes provided by individuals I had met during my visit to Fullerton.

INSURANCE

Many Marine Insurers were present at the Southampton Boat Show so I did the rounds with them in parallel with my approaches to the boat-builders and their Agents.

Noticing many Insurance Companies often seem to have Impressive Offices and prosperous looking Boards of Directors I wondered if I could afford insurance if I bought a boat.

I was relieved such companies’ financial security is overseen by the Bank of England and their behaviour by the Financial Conduct Authority (or rather their predecessors in the late 1990’s), but reflected this regulatory superstructure must create a large overhead cost and couldn’t help wondering whether the Competition and Markets Authority carried enough weight to protect consumers’ pricing interests.

Generally I am only interested in taking out insurance for High Value Assets against events with a low probability of occurrence. The high value criterion would certainly apply in this case and I was confident I could ensure a low probability of disaster by taking a prudent approach to the way I sailed the yacht and developed my cruising lifestyle – but would an insurer think the same?

One certainly didn’t – a broker told me a British underwriter whom he consulted told him – “Don’t bring me rubbish proposals like this”.

During and after the Boat-Show I found a German-owned Insurer (or perhaps a British franchisee) who was satisfied I was a good risk by the way I had begun my sailing life and planned to continue. He offered me a Policy covering sailing in a geographic box defined by Bergen and La Rochelle from North to South, and from the Western Baltic to a few hundred miles into the Atlantic, west of the British Isles. I didn’t become responsible for Insured risks until after acquiring ownership in mid 1996 but was glad I’d started my investigations early because everything was lined up in advance by the time I took delivery.

I mention the insurance angle because the annual cost of boat ownership is an important consideration and insurance premia can be a significant proportion of that, along with maintenance and mooring costs.

At the opposite end of the spectrum to the one I have described some sailors carry out all maintenance themselves, find a remote mooring up a muddy creek that costs very little, and don’t take out any insurance at all.

There are many possibilities between these two extremes and one’s individual choice depends on one’s circumstances.

REGISTRATION

Whilst my yacht was being built I turned my attention to what name it should have and how it should be registered.

It is not strictly necessary to Register a small private yacht with the UK Government when it is intended to sail it in UK waters only. But if planning to go to other countries, registration is required so their authorities can be satisfied the yacht is British and subject to oversight by their UK counterparts.

Two forms of registration are available –

Part I Ship Registration applies to all vessels from any size of private craft to Oil Tankers and has these requirements and advantages –

Register your boat on the Part I register if you want to:

- prove you own the boat

- prove your boat’s nationality

- use the boat as security for a marine mortgage

- register a pleasure vessel

- get ‘transcripts of registry’, which show the boat’s previous owners and whether there are any outstanding mortgages

Your boat must have a unique name to be registered.

The Part III Small Ship Register is much less comprehensive and restrictive. It is only available for owners who satisfy these requirements –

- your boat must be less than 24 metres long

- you must be a private individual (not a company)

- you must live in the UK for at least 185 days of the year

- your boat must have a name

Well, I didn’t know what I was going to do in the future but I didn’t want to be limited by UK or Foreign officialdom and I did want to be able to go anywhere in the world if that is what I decided to do.

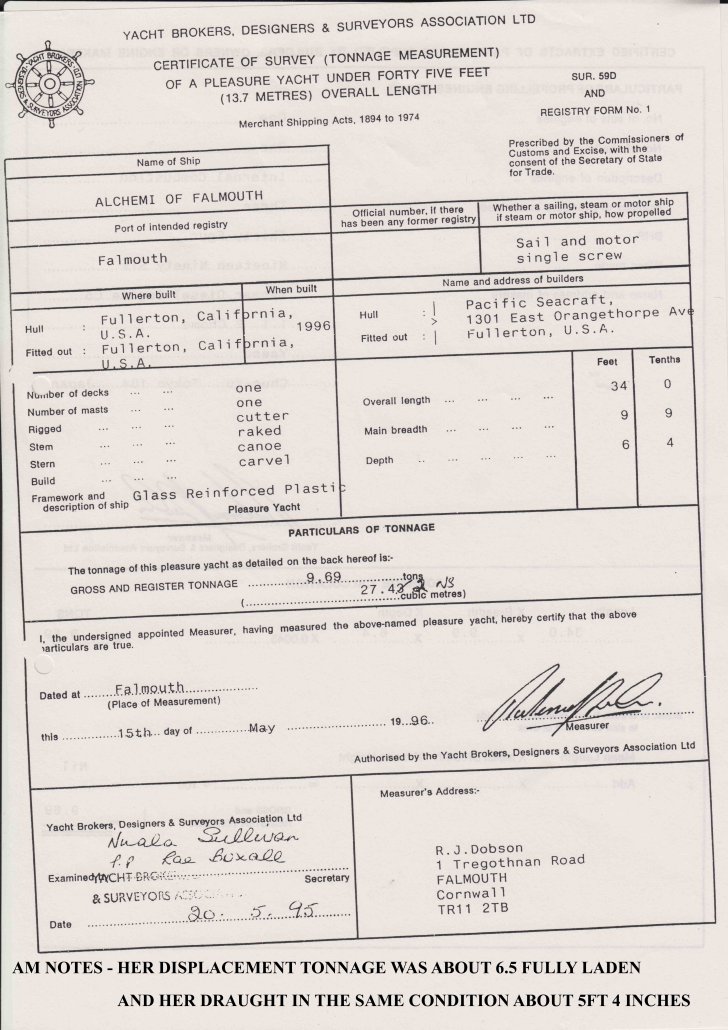

So, I applied for Part I Registration despite its higher cost and requirement for a Surveyor to be employed after the boat was delivered even though it had never been used.

That is necessary because a ship’s registered tonnage is nothing to do with its weight but is a measure of its presumed cargo-carrying capacity with each ton representing a volume of 100 cubic feet. The word is derived from tunnage which was the tax levied long ago on tuns of wine and its value is still used to determine commercial shipping dockage fees, canal transit fees and so on. Similar charges for small yachts are usually levied on length so a yacht’s registered tonnage is a virtually redundant measurement.

In fact, my yacht would have been unstable if an attempt had been made to load her to the certified level – I expect Customs and Excise were as keen years ago as they are today to avoid a shortfall in generating and collecting the revenue needed by HM Government.

The need for a surveyor was a nuisance and costly, but I had greatest difficulty in finding a name. My early thoughts soon had to be dropped (I liked the idea of Aeolus, God of the winds and son of Poseidon, but others had thought of that long before I did).

The procedure for getting approval required submission of a list of 6 possible names to the Registrar who would then let the applicant know if any were acceptable. After rejection of two lists of six I ‘phoned the Registrar and asked for help. I was told one of my second set could be accepted if I added the words “of Falmouth” to the name as that would make it unique. (Falmouth would be her “Home Port” because that’s where Pacific Seacraft’s UK agent was based).

So, my yacht came to be named Alchemi of Falmouth. I liked the idea of Alchemy because of its spiritual association for Sir Isaac Newton and others as well as the notion of transmuting the lead of my own life into gold. I chose to spell it with an “i” instead of the usual “y” because that made it an anagram of my given name.

Here is a copy of the Surveyor’s report qualifying my yacht for Part I Registration and sharp-eyed readers may note his secretary recorded the yacht was surveyed a year in advance of being built! They may also note the secretary had to correct and initial a typing mistake in the volumetric measure, but hey ho, regulations apply to the public but apparently not to the staff administering them. The Registrar didn’t complain and I only noticed myself when scanning the original document for this article 24 years later and 5 years after I had sold the boat itself.

© AM

This article concludes the introductory parts of my story that I thought it important for readers to understand before continuing with some of the more Human and Geographic aspects of long-distance sailing that I enjoyed during the following 18 years. I hope these early articles will help any others who may be thinking about making a similar life-style change.

As a final remark on that theme I mention that most of the boat-related problems I later encountered were due to my own ignorance and lack of attention to maintenance requirements on parts that failed. Most were with equipment to which I paid insufficient attention or that just wore out through use. I had very little trouble with the basic fabric of the boat, sails, or rigging, probably because mine was the 306th unit of the same design and most actual or potential problems had been discovered by my predecessors and corrected by the builder.

There were other types of problems of course, with weather, with some of the people who came with me as crew, and particularly with bureaucracy around the world, but like the piracy about which “el Cnutador” enquired, or watch-keeping and sleep patterns that “Demos” mentioned in their comments on my last article, those are parts of the story I’ve not yet reached.

To Be Continued…

© Ancient Mariner 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file