© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

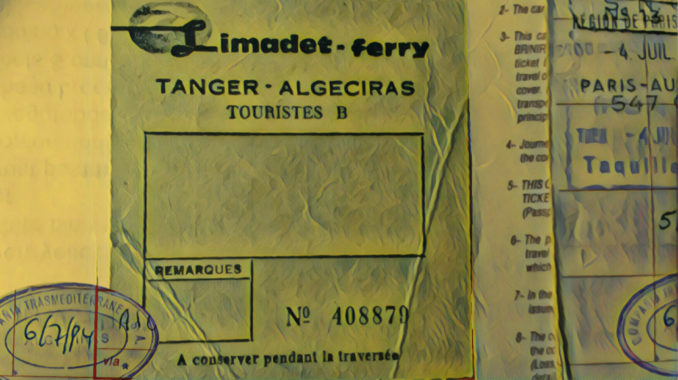

Sitting on the dockside at Algeciras, myself and Tammy dangle our dirty feet over the Eastern Mediterranean, next to a giant but idle Transmediterranea roll-on roll-off ferry. The ship’s company are enjoying their late afternoon strike, all enquiries being met with, “There is no problema”. We are enjoying the fresh air, sunshine and a conflab. A Muslim man prays nearby on his mat. Ahead of the three of us, lie the straights of Gibraltar. To our left, the rock itself, white and green, reaching to the sky, shaped like a fifteen hundred foot high saddle.

Our little conference is about operation Swaling, the reason why we are creeping towards Morocco, disguised as student buddy backpackers doing Europe and North Africa.

In ones and twos, more people gather. They mill about. Trucks start their engines. Men in uniform appear. The unwritten strike siesta timetable presents itself. A small jostling crowd of fellow foot passengers gathers about the bottom of a gangplank. It would be wrong to call it a queue. We join them, shuffling onto the ship and then shuffling forward until we stand as close to the prow as we’re allowed.

Having cast off, we pass the boring side of Gib. Unable to see the sheer rock face or water traps, we look towards the naval base and airfield which, at that distance, are tucked down out of sight.

Partway across, as if in Limbo, we could see Africa to one side, Europe to the other. Porpoises swam below us, keeping ahead of the bow. I held Tammy by the shoulders and pointed her back towards Gib.

“Here’s something that annoys me about the Spanish. They go on and on about the Union Jack flying over Gibraltar while holding on to Ceuta in Morocco.”

She gave me a pep talk on Tangiers. She had brought her own toilet roll, she trusted that I had too. Local toiletry etiquette included the use of the hand. Unhelpfully, she became confused between the right and the left. I remained ignorant of how to greet the natives (Tangerines?) without causing mortal offence by outstretching the wrong one. I would have to guess at it. It would have to do.

“And ignore people who pester you and follow you through the streets,” she instructed, “they lose interest after a few minutes.”

“Been before?”

“No.”

By now, still closer to the Spanish coast than the Moroccan, the ferry was heading east, waiting until directly opposite Tangiers before turning hard a-port and approaching the harbour by crossing the other, westbound, shipping lane.

Because of the strike, we were running very late and docked after dark, at about 9 pm. Disembarking, the sights, sounds and smells were African, as was the organisation. The ferry buildings were sparse and utilitarian concrete blocks. They were packed and noisy. We clung to each other in a crowded queue which inched forwards. By the time we had reached customs, the check consisted of little more than a uniformed man putting blue chalk crosses randomly across baggage. It suited our purpose. The last thing we wanted was to be searched.

Outside, the crowds thinned, if you passed as Moorish. For the lighter-skinned, there was a gauntlet of spivs and ruffians touting hotel rooms, train tickets, hashish and worse. More than one unpleasant looking type wanted to introduce me to his sister. All of this while I was holding Tammy’s hand, very tightly.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

A railway line ran right into the docks. No need for a platform, passengers embarked by hauling themselves, and each other, onboard. The late train to Casablanca had been held for ferry passengers. It was French-built, quite impressive. We clambered on, with no intention of going anywhere, in order to escape the mob. Although French on the outside, it was Moroccan on the inside. More simply laid out than the Gallic traveller would expect, wooden benches replaced seats. Many of the travellers were preparing supper. Some of the ingredients were still alive. Kindling was pilled in the aisles as if the cooking arrangements included setting fire to the rolling stock. After walking along two carriages, we disembarked on the opposite side, an old trick often used to confuse a pursuing mob.

This worked until we left the dock area, on the far side of whose gates we were mobbed again. We clung to each other again while striking uphill through narrow streets towards the old town, pursued. From the corner of my eye, I spied a line of pretty girls down by the dock wall, unmolested. Very strange.

The rugby scrum continued up the street like a smoke veiled cartoon fight, arms and legs going in all directions. Our late-night sightseeing involved no more than ourselves and our possessions being grabbed at, while threatening and crude remarks were shouted at us.

Tammy spotted something. Taking the lead, she pulled me forward. Ungentlemanly, I’d forgotten to offer to carry her big pack. She struggled beneath it whilst being pawed by the locals, more than one of whom received a firm slap from me for their cheek. Meanwhile, I was being held back. Someone was trying to pull my canvas knapsack from me. I began to worry that Tammy’s precious special camera might be stolen. I needn’t have. She ploughed on determinedly, dragging me behind her. Stopping suddenly, she pushed me side-ways. We clattered through some doors and entered a different world.

“Now that was a bit of luck”, she announced, breathless and sweating. About to remind her that there were two types of luck, I took a moment to appreciate my new surroundings. They were of marquetry and polished dark woods. Gentlemen and boys in little waistcoats and caps, busied about with luggage and silver trays. Polished leather shoes danced silently across exotic rugs. If Tangiers had a Sultan then we’d accidentally stumbled into his front room, if not his boudoir.

To one side, billowing silk curtains were tied to marble columns announcing the entrance to a dining hall.

“Beats making a fire on a train floor to roast up a recently decapitated duck,” I whispered.

“Welcome,” announced a giant moustachioed dark-skinned man in a business suit and fez. He had a name badge, written in Arabic, embossed in gold.

We were in the lobby of the Royal Maroc Hotel. Our new best friend in the whole world reminded us that there was a dress code. Not only were we in jeans, T-shirts and sports shoes but they had become somewhat dishevelled in the battle of the Rue de Ben Abdullah. At one point I’d been dragging an urchin along the ground as he tried to undo my laces. We bluffed our way into the place at any cost, anything to avoid the mob outside.

“My evening wear is in here,” Tammy announced confidently, tapping the steel frame of her giant backpack.

Wary that my entire luggage consisted of a small canvas satchel, now handheld as the straps had just been ripped off, I was pleased to announce.

“My suit and brogues are in her pack too.”

Killing the need for any further subterfuge, Uncle Sam marched to the reception desk (which was the size of two snooker tables), waving her plastic card. All became well with the world again. If Hieronymus Bosch had been stood in the corner painting the scene, beneath the tapestry of camels refreshing at an oasis, he would have put us back into the Garden of Eden (although fully clothed, for the time being). Picasso would have depicted a rebuilt Guernica. Arabs, Spaniards, Germans and ourselves would be chatting amiably over drinks, everybody friends again.

Beneath a lazily turning fan, whose blades depicted two gazelles apparently chasing each other around the ceiling, our room was sumptuous. My own little chase was about to end. A double bed beckoned beneath those appropriately prancing beasts. We had our own bathroom. Too hot for carpets, and the Sultan perhaps not being keen on wallpaper, there were tiles everywhere. A million shades of ceramic blue, patterned with golden decagons, rose to the ceiling. Beyond slatted window shutters, Tammy stood on the balcony (yes, we had a balcony), looking out over the lit towers and minarets of old Tangier. Beneath her, the speckled lights of the kasbah gave way to the occasional dot of illumination in the desert far beyond.

I stood behind her and placed my arms around her waist. Above us, a satin night sky of stars was interrupted by the thinnest of silver crescent moons. Freed of station washrooms, nun’s hostel communal sinks and train carriage toilet compartments, we had taken turns in the giant bath. All four of our feet were finally shiny clean. We wore matching his and hers bathrobes embossed with giant interlocking embroidered R’s and M’s. As if a character in one of the better stories from of the Arabian Nights, I could hear a talking bed whispering to me. “Room on me for two,” it pleaded.

“Three cheers for the Sultan, say I, and the best hotel in the world.”

I snuggled my mouth into her neck and mumbled. My hands began to wander, my lips to look for hers.

Tammy was in a different story. She had noticed something important. The talking bed was silenced. Was it Scheherazade who told the tale of the frustrated herald being tortured by having his liver pecked out? For it to grow again so that the process might be repeated? More likely to have been Hesiod. Although my predicament centred upon the genitals, I sympathised with Prometheus all the same.

This is what she’d spotted.

To be continued…..

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player