Budapest VII. Erzsébet (Lenin) körút 44-46, Fortepan – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Friends tell me that I’m a ‘Master Raconteur.’ At least, I think that’s what they’re telling me. Perhaps it’s an anagram? No matter, I must recount the following. Every tall tale should have its own walking tour. Would you like to follow your humble author around Lille? What? You’d rather dress as George Sewell and meander Gateshead’s municipal car parks hearing about Jack Carter and hard-knocks up the North? Oh. Be careful what you joke about. In fact, it takes a very brave man to joke about anything these days. In the strange times that we live in, there’s nothing funny about humour. For a walking tour there is. In your unread comments, I noticed the following:

‘Where were your accommodations in Budapest?’

A reference to my other humble work’s Episode 7, ‘Socks, Shoes and the Orient Express.’ Happy to oblige, I sent a message back, ‘44-46′. The proviso being that the street name will have changed. One assumes, thirty-five years later, not much will be named after ‘Lenin’ in contemporary Middle Europe. I also mentioned that, back in the day, one side of the ground floor was a second-hand wedding dress rental service. Look out for it, you never know, it’s surprising what survives. I thought nothing more of it but the next thing I know, a photo has arrived captioned,

‘Do you recognise this?’

Yes, the first walking tour (that I know of) had just taken its first photo, of the first punter, outside a ‘Postcard from Lille’ location: the entrance to Erzsébet körút 44 – 46. Am I due a commission?

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

I know I shouldn’t have, and I know you won’t believe me, but, dear reader, I went a bit dewy-eyed. Closer inspection showed that the dress-hire outlet may have survived, there being a big black and white Soviet-style wedding photo in the gap above the doors. It’s surprising what’s lasted and what hasn’t. Communism? Nope. Roman Empire? Nope. European Union? Borderline. Wedding dresses? Of course. The Tooth Fairy? You bet! Santa? Indestructible. Expressing my gratitude, I cheekily asked, ‘Can you get inside?’, citing as a ‘must-see’ the first thing that came into my head, the old Hapsburg solid iron lift (that never worked).

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

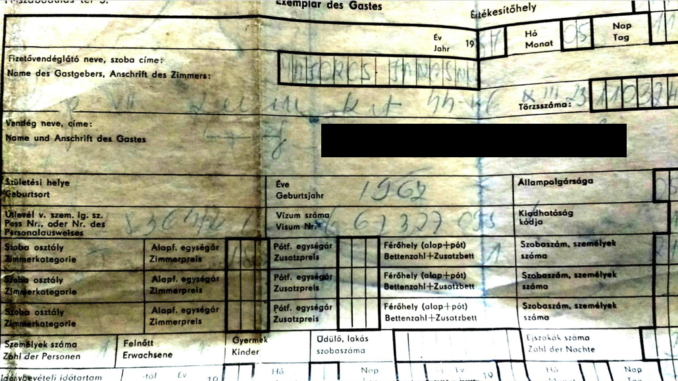

Wary that I might have sent a good chap to the wrong place, I felt obliged to the attic to address my derring-do box and unearth my old Ibutz registration. Sure enough, my residency was marked out as such, in the local back-to-front style (my brackets):

BP (Budapest), VII (District Seven), Lenin Krt (Korut means boulevard), 44-46, V (crossed out and corrected to) iii 23

To distinguish between the different parts of an address, the Hungarians use a mixture of Roman and modern numerals. If I’d been on the ii floor, instead of the iii, then I might have had an even better tale to tell but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Something jumps out from that form and slaps one about the face. Can you see what it is? No? You’re in good company, I missed it for nearly four decades. As you know, fizetovendegalato neve means ‘Name de Gastgebers’, which is a bit easier to translate. Within the box to the right of that text, and above ‘Lenin Krt’, is the name of that host family, and I’m not joking, it really does look like, in the backwards style and local spelling, The George Soros’s. Google calls.

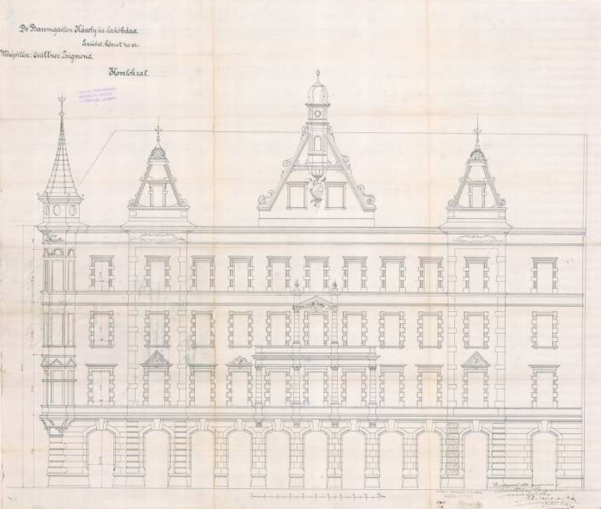

Lenin körút (krt.) was originally named Erzsébet körút, with block 44 to 46 being completed in 1889, in accordance to the plans of Zsigmond Quittner whose client was the lawyer Karoly Baumgarten. The Baumgarten’s family wealth derived from crop trading, which allowed for several ‘rental palaces’ to be built. Including the attic rooms, it was five stories high, the lower floor and inner courtyard being retail outlets. The lower inner courtyard was a café, the three balconied floors above led to palatial apartments.i

Architect’s Drawing, Hungaricana – Public Domain

Externally, by local standards, Quittner’s design was rather plain and would have appeared little more than a grey tenement, had it not been for the pitched embellishments about the attic windows and a spire added to the top of the street corner at Dob Utca. What kind of a Budapest did 44-46 emerge into? I am indebted to Robert A N Harvey who provides us with this contemporary account from the Morning Review:

‘Budapest is a very beautiful city and only second to Vienna. Its grain trade is immense; is connected by a suspension bridge 150 feet high and 1,300 feet long [connecting Buda and Pest]. Budapest has superb buildings. Its hotels rival those of any city in the world. Its academy has 800 paintings, 50,000 engravings and 12,000 drawings. The railway stations are marvels of costliness, surpassing anything in America. The Jews have here the finest synagogue on the continent. The Greeks have a beautiful church. There is a large building, gorgeously decorated, built by the municipality solely for balls and private parties. There is a magnificent theatre, built and supported by the government. All the royal palaces and government buildings in Austro-Hungary are painted a bright yellow.’

Having enthused about Budapest, he is less keen about the countryside,

‘An Hungarian peasant village is far from beautiful, the absence of trees and the presence of dirt and mud are its striking peculiarities. If the peasants are farmers their houses are clustered together, while the farm lands they till stretch away for miles in every direction. The interiors of the peasant homes are not unattractive, the floors are of stamped earth as wood is scarce. The peasants are content to obey the master of the manor and the village priests.’

And somewhat lukewarm about the gypsies,

‘In the gypsy villages they herd together like animals. There is no marrying or giving in marriage. Both sexes go nude until fourteen. They have no written language. They mostly live by plunder, though they profess to be horse dealers.’

Harvey outlines a Hungary where there is a great difference between Budapest and a countryside, Austro-Hungary’s grain basket, owned by absent landlords. Hungary is a place of many different peoples, distinguishable and segregated by culture, language and genes.

‘5% of the entire population are Jews, 18 percent of the university students are Jews, and 2/3 of these study jurisprudence. Jew and gentile have little love for each other. Marriage between them is not permitted.’

That Jewish population wasn’t evenly distributed. In the 1900 census, the population of Budapest was 703,000, 23% of whom were Jews. In Erzsebet Krt.’s District VII the proportion was 36%, the highest of any district. The Jews also tended to be better off than other Hungarians and were notably well-represented amongst the professions and landowners. Likewise, in their living conditions, 75% of Jews lived in dwellings which consisted of more than one room, as opposed to 37% of Christians. As such, 44-46 was high-class accommodation, built by Jewish businessmen, on the Easternmost side of Pest’s Jewish Quarter.

Upon completion, one entire floor was occupied by Mor Jokai, a prolific writer, chronicler of the Hungarian revolution of 1848, the Hungarian Charles Dickens. He lived there with his second wife, twenty-year-old actress Nagy Bella, scandalously fifty years his junior, the old goat. Shall we steal a phrase from the local Finno-Ugric? Sezexbolondot, ‘sex fool’.

Jókai Mór Nagy Bella Erdélyi, Mor Erdélyi – Public Domain

Speaking of twenty-year-old Hungarian girls, your humble author’s landlady could hear tip-toeing size four feet, in her sleep. She could also, from behind closed and bolted doors, see a little sliver crucifix bouncing between cleavage in the moonlight. She would emerge from her room, limping at great speed, striking her walking stick to the girl’s backside with impressive accuracy. The kind of thing a Soros might do?

This was, fortunately, all the fault of the ‘filthy local girls.’ Old granny Soros not only mothered me but recommended a lonely niece, marooned loveless in a Romanian enclave in the provinces, who, ominously, was being sent for. Dear God. Razor-sharp regular readers, with instant recall, an IQ of over two hundred, a photographic memory and a suspicious mind, might tell you that Sonya the Camgirl’s aunty might be exactly the right age. I cannot possibly comment.

Returning to the last years of the nineteenth century, Jokia and his wife occupied part of the second floor of the residence, with other members of his extended family occupying the rest. My Hungarian isn’t great. Also, Hungarian women change their name upon marriage, but not necessarily to their husband’s. They then use their maiden name, husband’s name and married name interchangeably, often back to front. A situation not helped by nearly all of them being called ‘Bela’ and those that aren’t, being called ‘Bella’. From this position of disadvantage, as far as I can work out, my research indicates that the inhabitants of those palatial second-floor apartments fought like cats in a sack.

Jókai in his study., Mor Erdélyi – Public Domain

Jokai would winter in the south of France and return to Pest in the Spring. In 1904, upon his return, he was taken ill with influenza that developed into a pneumonia which took his life, aged 80, on December the 19th of that year. The building’s owner, by then coffee house magnate Mr Leo Berger, named the building after him. No, not ‘Sex Fool Towers’ but ‘Jokai Udvar’. A plaque was installed on the outside ground floor of the Dob Utca (or ut. meaning street) corner.

A sign to that effect (which remains to this day) was erected above the fourth floor, facing Erzsebet krt. Udvar may be translated as ‘house’ or ‘court’, but I prefer ‘courtyard’ as if country ground enclosed by farm buildings, or in his case a covered courtyard surrounded by apartments. In order to up the family feud to max, Jokai left all of the rights to all of his works to his young wife, Bella. As ever, the simple young actress knew the soul of the rich old man better than anyone else hoping to inherit.

Orczy-Haus Budapest, Buchhandler – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

From 1910, the ground floor, of what we may now call ‘Jokai Udvar’, included the Circle café. Operated by Jozef Weiszberger, it was frequented mainly by writers and teachers. A note on café life. Zsigmond Móricz describes another coffee house, at the Orcazy-Hauz at the other end of District VII, thus:

‘Who were the people that frequented the place? Furriers and textile merchants. You should know that millions changed hands here. Practically speaking, this is where the stock exchange was. That was the heyday of the café, when every day there were 50 carriages parked in the courtyard. That’s when the merchandise found its way here; this is where the city’s commercial arteries beat, among the three courtyards.’

One of the merchants will have been Mor Szucz, a partner in Marcus and Szucz, a fabric shop on Petofi Street, the most fashionable street in the then booming Budapest. The Szucz’s had a daughter called Erzebet. To prevent endless Bela and Bella type confusion between Erzebet and Erzsebet krt. we shall call her ‘Miss Szucz’. She was to marry a Tivadar Shwartz, a boarding school and university graduate from the provinces, studying law in Budapest. ii

As per Móricz’s description, Cafes were places of intense discourse. Shall we picture the teachers and writers of 44-46’s Circle café as intellectuals whispering summarised Proust in a chess farm? Or as a place of intellectual debate and political agitation, during a time of great upheaval across Middle Europe and revolutionary Russia?

The National Association of Teachers was founded at Jokia Udvar in 1918. This was not as a modern Trades Union, rather as a vanguard for radical change. By now, the Central Powers, which included Austro-Hungary had lost the First World war.

The boulevards throbbed with an influx of disgruntled soldiers, many of them radicalised as prisoners of war in Bolshevic Russia. Trouble brewed in the streets. A left-wing government, which included many Jews, turned into a ‘Red Terror’. A counter-coup overthrew the Reds and replaced them with a ‘White Terror’, some of which was aimed at Jews. The patrons of the Circle café and the residents of the apartments above, will not have been immune.

Austro-Hungary had ceased to exist. The new Kingdom of Hungary did badly out of the treaty of Trianon (1920), losing most of its territory to the hated Romanians and the newly formed countries of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. We must now picture Budapest, including Jokai Udvar, packed with ethnically cleansed Hungarians who had fled from lost territories.

The Berkeley Daily Gazette of December 27th 1922, offers the following eye witness account from its alumni, Russel White Bell, of the American Relief Agency.

‘He told of the misery of the men, women and children of the Hungarian middle class, and of ‘hall bedrooms’ which he had himself seen occupied by four or five persons, describing housing conditions so congested that 4000 families by actual survey lived last winter in unheated boxcars in Budapest.’

Many of the city directories from the 1920s have survived and show the inhabitants of 44-46 to be largely professional people and business owners, many of them Jewish. The Circle café has an athletics and swimming club. Jakab Hegedus is a doctor, as are Zsigmond Szekely and Dezso Ungar. Istavan Bojar and Erno Tepper are lawyers. Odonne Weiss is in business. Somogyi Mor advertises his music school. The building is now owned by Gisella and Dora Perlmutter. A few blocks away, the artist Isaac Perlmutter’s palatial family home is at Andrassy krt. 60.

Nearby, Miss Szucz and Tivadar Swartz married in 1924. As well as running a legal practice, Tivadar also took responsibility for his wife’s family’s financial interests, which included properties in Budapest, Vienna and Berlin as well as the family’s fabric store. In 1926, the now Mrs Swartz gave birth to a son, Pal, and in August 1930, to a second son, György.

As Budapest’s fortunes improved, so did the Swartz’s. They moved to a desirable area, a large apartment opposite the Hungarian parliament building in Kosoth ter. They acquired a summer house on Lupa, one of the Danube islands, which was designed by, and shared with, George Farkas and family, the architect husband of Mrs Swartz’s sister Klara. Winter holidays were taken in Austria. Pal Soros was to become an Olympic skier.

Budapest continued to boom, not least because of its close political and economic ties to Austria and Germany, countries that were now beginning to pass anti-Jewish laws. In 1936, aware of the sensitivity surrounding their travels to Austria and business interests in Germany, the family changed their names, and six-year-old Swartz György became George Soros.ii

As Europe marched towards war, so did Hungary. Two ‘Jewish Laws’ were passed there in May 1938. In February 1939 Hungary joined the Axis (although the Tripartite Pact wasn’t signed until November 1940), in return for which they were ceded some territories lost at Trianon. Life during the first years of the Second World War proved to be little different than before. All changed in March 1943, when the Hungarian army, along with their German allies, were defeated at Stalingrad. Eighty thousand Hungarians were killed or missing and sixty-three thousand wounded.

On 19 March 1944, Germany invaded their by now faltering ally. Within days, Adolf Eichmann had arrived, tasked with making Hungary Jew-free. During May and June 1944 437,000 Jews were transported, nearly all from the countryside rather than from Budapest. Ominously, in the 1944 home data sheets, the number of residents and landlords obliged to wear the yellow star must be listed. Properties are categorised as being Jewish or non-Jewish. From 21 June 1944, Budapest’s Jews were concentrated into ‘Jew houses’ or ‘yellow-star houses’, named after the yellow Stars of David pinned onto the properties. According to yellowstarhouses.org, 44-46 wasn’t a yellow-star house but the neighbouring properties at Dob ut. 60 and Dob ut. 65 were. As were Erzsebet krt. 41 opposite, and Erzsebet krt. 50 and 38 nearby.

A large proportion of the yellow-star houses were in or near the existing Jewish Pest Ghetto, which included 44-46, but many others were scattered around Budapest perhaps to dissuade the allies from bombing the city. We must now imagine the wealthy, professional Jewish families of 44-46 cleared to yellow-star houses or concentrated into Eichmann’s ghetto which was still within District VII but closer to the Danube. ‘Clearing’ would have meant the sequestration of their possessions and their apartments, which would fill with refugees fleeing the advancing Soviet army. Such ‘clearings’ were aided by a young George Soros, now living as if a Christian.

Jokai’s wife, Bella Nagy (also known as Jokaine Nagy Bella and Grosz Bella) had left at the outbreak of war and gone to live in London, where she died in 1947, aged 67. George Soros’s uncle, George Farkas, and his wife Klara were to leave in 1945. The Perlmutter’s palatial residence at Andrassy krt. 60, had become the headquarters of the Hungarian version of the Nazi party, the Arrow Cross.

Budapest, Festnahme von Juden, Faupel – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

The photo above (dated October 1944) shows arrested Jewish women being marched past Wesselenyi Street. This intersects Erzsebet krt. at block 30–42. In the other direction, 44-46 will have witnessed marches towards the international ghetto, opposite Margarit island, where Jews who had protected passports were concentrated. This is at the northwestern end of Erzsebet krt. by which point it is named Szent Istvan. Also marching, a column making their way to the railway, for the controversial ‘gold for blood’ train for those who paid to leave.

The Soviet and Romanian offensive against Budapest began on 29 October 1944. In December, Eichmann’s ghetto was walled-in and many more Jews were concentrated within it. At its closest point, this ghetto was about a hundred yards to the west of 44-46, in the direction of the Danube. By 26 December, Budapest was encircled by the Soviets and under heavy bombardment. Residents were starving and jammed into bomb-damaged buildings.

During my stay in the nineteen-eighties, the existence of internal pre-war ornamentation suggested that 44-46 wasn’t badly affected at this time. Judging from the old photos, Buda took more damage, it being much hillier than Pest and the obvious place to mount a stout defence. The siege ended on 13 February 1945 in unconditional surrender. By this time, 38,000 civilians had died, 13,000 in the fighting and 25,000 from starvation, 80% of buildings had been destroyed or damaged. Budapest’s privations hadn’t ended. The starvation continued. There was no wood for heating or cooking, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians were deported to Soviet labour camps.iii

Elections in 1945 returned a multiparty parliament with the Communists only getting 17% of the vote. Strong-arm tactics resulted in the Hungarian Workers Peoples Party standing unopposed in the 1949 elections after which the Peoples Republic of Hungary was declared. Between those two elections, on 13 May 1948, George Soros’s brother, still known as Pal, defects to Austria. His application for Displaced Person status, while residing in Salzburg, leaves a paper trail. On the digital version, his birthday is incorrect (to throw us off the scent?) but on the actual card index, his details match. He notes his relatives as being his parents, who are still resident in Budapest. He omits to mention his brother Geroge and lists his only other relative as his uncle George Farkas, now resident in Miami.

Pal Soros’s previous occupations are listed on his application. I would love to translate his wartime experience as if from ‘Undersee Kriegsmarine’, as though a U-boat commander torpedoing fleeing orphans, but I’m afraid I must be honest and translate it as the (sort of looks a bit similar to that in German) ‘Without work because of wartime.’ Also listed are his ski trips to Austria, including as an Olympic skier. On 2 March 1949, his application is stamped as ‘Ineligible’, by which time he had already emigrated to the United States. George Soros had previously left for the United Kingdom in 1947, joining his brother and uncle in the United States in 1956.

Also in 1956, conditions in Hungary, and discontent with the Communist regime, reach boiling point. In October of that year, an uprising begins. One of the bones of contention was the allocation of housing to Communist party lickspittles, who presumably occupied a cramped and austere 44-46, on a boulevard now re-named ‘Lenin krt.’. Maybe the writers and journalists that helped to spark the uprising were agitating in the café, perhaps as one of the anti-Communist organising forums?

Erzsébet (Lenin) körút – Király (Majakovszkíj) utca saro, Fortepan – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

One of the first events of the uprising was a protest march, which is pictured at the junction of Lenin and Kiraly, the next street corner in the opposite direction to Dob ut.

Erzsébet (Lenin) körút 44-46, Jókai udvar a Dob utca sarkától nézve., Fortepan – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Lenin krt. 44-46 shows signs of violent conflict, especially to the upper stories, perhaps because of sniper activity. Soon after, the uprising was put down by a Soviet invasion and by 10 November 1956 Budapest had been pacified. Hungarian casualties totalled around 2,500 dead with an additional 20,000 wounded. Budapest bore the brunt of the bloodshed, with over 1,500 civilians killed.iv

Dob utca – Erzsébet (Lenin) körút sarok, Fortepan – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

A woman sells flowers on a battle-damaged corner of Lenin krt. 44-46 in a now pacified Budapest. It is January 1957. The plaque commemorating Jokai remains and can be seen to the left-hand side of the photograph, on the Dob ut. corner. In the immediate aftermath, many thousands of Hungarians were arrested. Eventually, 26,000 of these were brought before the Hungarian courts, 22,000 were sentenced and imprisoned, 13,000 were interned and 229 executed. Approximately 200,000 fled Hungary as refugees. iv

Two of those refugees were Tivadar and Erzebet Soros who joined their sons and in-laws in the United States. At this point, dear reader, following the extensive research outlined above, there being only four Soros’s and all of them living in America since 1957, I’m forced to concede that it is probably most unlikely that I was sleeping in George Soros’s spare room in the 1980s. I think we all suspected that anyway. Apologies to his grand-mother.

The Soviet version of events conceded that the Hungarian government had made mistakes but that the discontent had been hijacked by fascists, Hitlerites, hooligans and the West. A new Hungarian government was formed, with Soviet approval, under Janos Kadr who was General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party for the next thirty-two years, until the tail end of the Cold War in 1988. During this time, Hungary became the happiest hut in the Eastern Block barracks. Not a high bar, given conditions in places like Enver Hoxha’s Albania, Ceausescu’s Romania and General Jaruzelski’s Poland.

Erzsébet körút – Dob utca kereszteződés, Fortepan – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Now, dear reader, I hear you ask, what was 44-46 like in the 1980s? It, and my landlady, were as described in Episode 7 of ‘Postcard from Lille’, which can be read here. May I add the following from my contemporary journal?

‘Mrs Majoros is a stalwart of the Ibusz system. They need her spare room, she needs the money. Her apartment is central, on Lenin Korut. As well as her percentage, she commands sufficient commission (for two bottles of good quality wine a week), from washing, ironing and cooking meals (payable in hard currency rather than the Forint she receives from the Tourist Ministry). Her son lives there too. He is very tall and finds himself extremely important in his Polish leather jacket and worker’s strides. He is monosyllabic and has an impossibly large moustache. She had a daughter too, somewhere. Mrs Majoros has rules. They are set in concrete.’

‘There is to be no bringing dead pigeons onto the premises, as the North Vietnamese do, or making fires from twigs and leaves on the floor of your room – as the Moldavians. Guests can use their own room as they wish (unaccompanied obviously) and can use the toilet and bathroom (for a maximum of 15 minutes). If a lukewarm bath is required, a bath plug can be hired (rates vary) for a maximum of twenty minutes. Guests have to be in by 10pm, as that’s when the porter locks the doors to the street. But not before 5pm, as guests would be best occupied walking the streets before then.’

‘Guests might occasionally be invited into the front room, at Mrs Majoros’s discretion. The final and most important rule was that house rules applied, and were likely to vary at any time. If you are polite, well dressed and good mannered, Mrs Majoros will insist that you are German. You must call her, ‘Frauline’. She will address you in a pigeon Germano-Fino-Ugric, which is easy to understand.’

‘Frauline is quite small and wears thick glasses which do nothing for her looks and little for her eyesight as she carries a large broken magnifying glass with her at all times. On our first meeting she showed me the bathroom, with its huge wooden toilet, and my own small room, partitioned from the corridor, next to the front door. It contained a bed, high ceiling, large wardrobe, round table, mirror, three paintings (two rustic, one metropolitan), two lights and a chair. It was carpeted partway up the walls and, most importantly to a landlady, would contain my rent-paying self. Opening the curtain of my high narrow sash window showed a view across the balcony and down to the courtyard.’

‘To lock the front door, the key went two times clockwise, was returned to the vertical and then withdrawn. It was unlocked by two anti-clockwise turns and then a gentle pressure upon the frame during a third half turn. As a German, even if you lock yourself out, she will rise to let you in. Unlike the Poles who are left to sleep on the step and Albanians, not only left there but forced to scrub it the next day.’

‘Do not kiss your door key while walking past comrade neighbour Ivonova’s wayward daughter’s window, she who sits all day dressed only in a towel. Frauline Majoros will notice, even from behind the closed and shuttered windows of a pitch-black 9:59 pm Pest street corner.’

That contemporary account goes on to mention days without water, heating or food. Shops are empty. Military conscripts are emaciated, many without boots, their trousers held up with string. Buildings are cheaply and shoddily made. Newer apartments are cramped, damp and drafty. There is a shortage of paint, wood, metal, light bulbs and paper. Away from Budapest, the countryside remained similar to Harvey’s description from the late 1890s. Roads were of compacted mud, ploughing was by hand. Boats, fords and chain ferries made up for a lack of bridges.

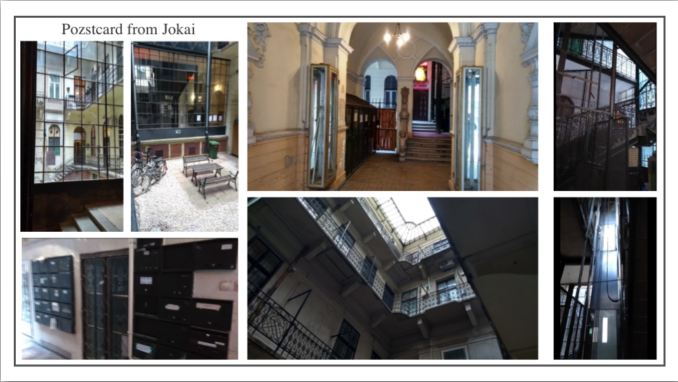

I receive another message, ‘I’ve got in but now I can’t get out.’ Shall we photoshop our (trapped) walking tour punter’s modern-day photos into a postcard from Jokai Udvar? I think we should.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

In the modern-day, there’s an H-Dent dentist on the bottom floor. The Hapsburg lift has been enclosed. The place has had a lick of paint and is properly illuminated, showing some of the original ornamentation. Part of the top floor is a hostel which (via Tripadvisor) looks suitably ‘Ikea’ sparse and has been even further partitioned, making it look more cramped than forty years ago. However, there seems to be double glazing and no doubt there is wifi. Some of the apartments seem to be private residences, with air conditioning and little tables set for breakfast on the balconies. Which is rather cute. The courtyard itself seems to be private, with separate key access for residents.

Erzsebet korut Jokai-haz, Attila Terbocs – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Outside, there is still a row of retail outlets on the ground floor, all of them occupied. At the left-hand, Dob ut., side there are Hamdi stores branded as ‘Confectionary’ and ‘Ice Cream’. Hamdi claim to have been there continually for over one hundred years but their outlets can’t be seen in the older photos.

Andrassy 60 krt. is now the Terror Museum, George Soros is a billionaire investor and ‘philanthropist’. Klara Farkas died in Miami in 2104 aged 103. Pal, latterly Paul, Soros died in 2013, a shipping magnate. I’m sitting here typing this and worrying about our punter. The chap seemed so keen that I gave him a few more places to visit. Some were genuine, some I just made up. In his last photo, judging by the flora, and the orientation and colour of the moss, I would suggest that he’s in a tent in the woods near Bratislava. Are there still bears and wolves? Hope he’s OK.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

vég

i Mesélő Házak, ‘A Jókai Udvar’

ii ‘Soros’ by Michael T Kaufman

iii ‘Siege of Budapest’ Wiki

iv ‘Hungarian Revolution of 1956’ Wiki

Additional material; Hungarivana, the Hungarian Cultural Heritage Portal, Péter Buza, György Gadányi & Lásd Budapestet.

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file