The rise and fall of coca wine

Coca leaves have been used as a stimulant in South America for over a thousand years, especially in the Andes to overcome the fatigue of living and working at high altitude. Taken on their own they have no effect, but when the leaves are made into a wad with a little alkali such as lime, chewed to extract the juices, and placed in the cheek so that the liquid is absorbed by the mucous membranes, the active principle, cocaine, is released and efficiently absorbed.

The natives often added tobacco, another American plant, to the mixture, producing what Nicolas Moñardes described in 1569 as ‘great contentment’.

However, the Spanish settlers dismissed this as a mere native practice, and it was not until the middle of the 19th century that coca came to the attention of Europe. In Charles Kingsley’s novel of 1855 Westward Ho!, a band of English adventurers in South America in the Elizabethan era, have just liberated some natives from enslavement by the Spanish:

‘… the slaves followed, without a sign of gratitude, but meekly obedient to their new masters, and testifying now and then by a sign or a grunt, their surprise at not being beaten, or made to carry their captors. Some, however, caught sight of the little calabashes of coca which the English carried. That woke them from their torpor, and they began coaxing abjectly (and not in vain) for a taste of that miraculous herb, which would not only make food unnecessary, and enable their panting lungs to endure that keen mountain air, but would rid them, for a while at least, of the fallen Indian’s most unpitying foe, the malady of thought.’

The Italian scientist Paulo Mantegazza experimented with coca in 1859 and, perhaps carried away by its effects, wrote: ‘I would rather have a life span of ten years with coca than one of 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 centuries without coca.’

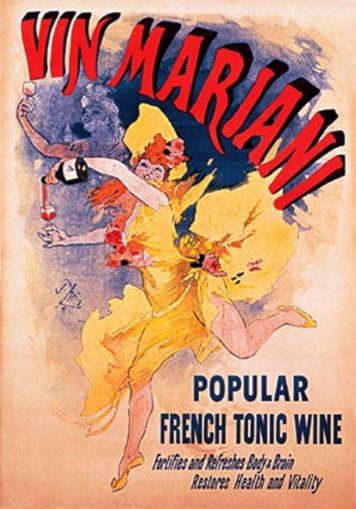

Inspired by these words Angelo Mariani, a chemist from Corsica, worked to develop a marketable version of the wonderful herb. He fortuitously discovered that, in a mixture a mixture of coca and wine, the alcohol extracted the active principle from the leaves and made it possible for the body to absorb it. Mariani launched his product in 1863 under the name Vin tonique Mariani à la Coca de Pérou, or Vin Mariani for short.

A small glass, 100 ml, of this wine contained the equivalent of 21 mg of cocaine and, while it’s hard to compare the effects of absorbing the drug in different ways, it must have had the effect of a substantial snort of the modern powder. and its effects would have lasted longer. Additionally, cocaine and alcohol interact in the liver to produce a new compound, cocaethylene, which adds to the euphoric effect.

It was claimed that Vin Mariani was made from fine Bordeaux wine, though in the late 19th century that meant little and much of what was described as ‘Bordeaux’ came from Algeria. Accounts of its alcoholic strength vary from 10°, the usual strength of decent red wine in those days, to 16° which would have required some fortification with brandy. Probably the formulation changed as time went by. The wine was sweetened, as was necessary to disguise the taste of the added coca.

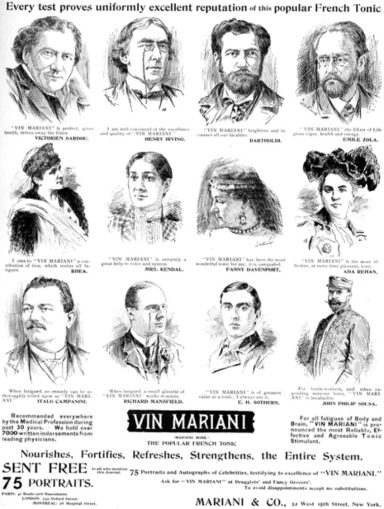

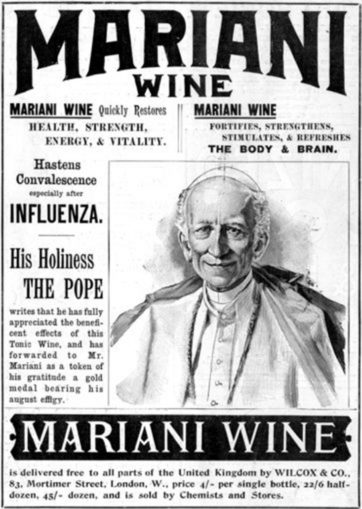

Mariani’s product was quickly successful. Unlike most of the useless ‘tonics’ of the time it really did stimulate and relieve exhaustion. Sales were boosted by the astute Mariani who sought recommendations from from the great and good, probably solicited with the offer of a few cases of his wine, and used them in his advertisements.

He got testimonials from, among others, the US president Ulysses S. Grant, the inventor Thomas Edison, the novelist Émile Zola, the composers Charles Gounod and John Philip Sousa, – and, most notably, two popes, Leo XIII and Pius X. He actually got Leo to award him a Vatican gold medal and, with or without authorisation, the pope’s picture was used in Vin Mariani advertisements. (Note, though, that the pope who came up with the doctrine of papal infallibility, which sounds like a coca-induced fantasy, was Pius IX, not as far as is known a consumer of Vin Mariani.)

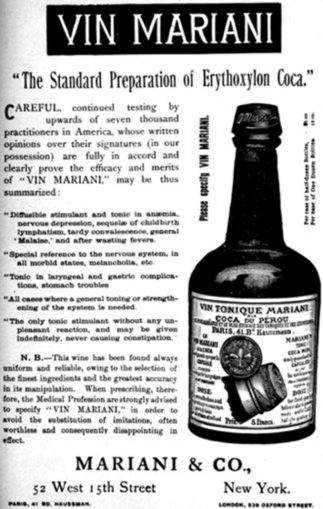

Medical opinion was sought, probably with the incentive of cash, and some fine-sounding lines were harvested for the advertising: ‘Tonic in anaemia, nervous depression, sequelae of childbirth, lymphatism, tardy convalescence, general malaise, and after wasting fevers. Special reference to the nervous system, in all morbid states, melancholia, etc.. Tonic in laryngeal and gastric complications. May be given indefinitely, never causing constipation.’

The new fashion was not restricted to tonic wine. Pure cocaine had already been isolated from coca leaves in 1855 by the German chemist Friedrich Gaedcke, and in 1860 another German, Albert Niemann, developed a practical purification process.

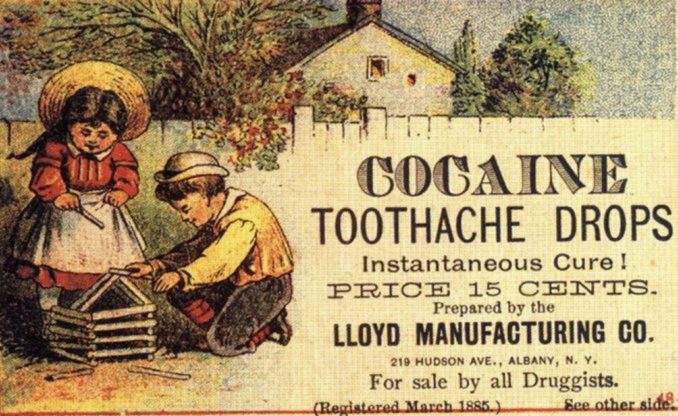

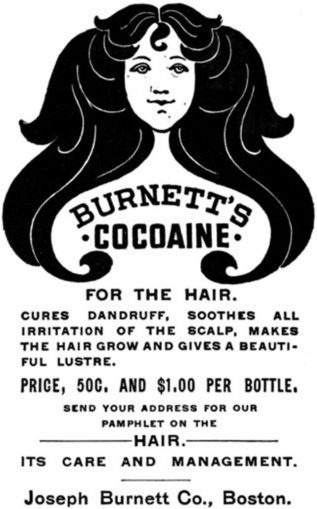

Like any newly discovered drug, cocaine was widely touted as a cure-all. Claims centred on its ability to relieve tiredness, which it undoubtedly did, and it was described as a ‘nerve tonic’ or ‘brain tonic’. Its function as a local anaesthetic was also noticed, and it was used by dentists and other practitioners to relieve the pain of minor procedures. Cocaine found its way into all kinds of products, from drops to relieve the pain of toothache in children to hair tonic – a use in which, applied externally, it can’t have had the slightest effect.

You could buy cocaine off the shelf in pharmacists. Naturally it also became a recreational drug, in the form of an injected solution. Its most famous user, though a fictional one, was Sherlock Holmes, whose habit was strongly disapproved of by his companion Dr Watson.

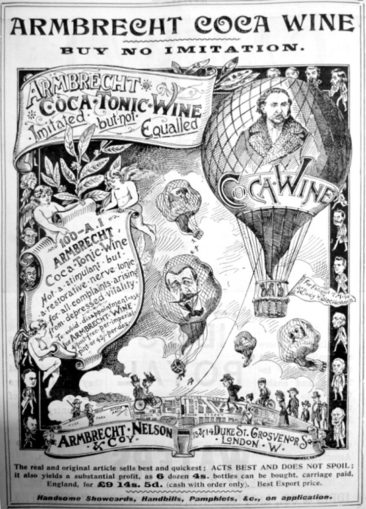

Vin Mariani was soon imitated, mostly with wines containing more coca than the original. In return Mariani started making a stronger export version containing 25 mg of cocaine per 100 ml glass.

Claims for the copycat wines multiplied.

‘Produces a general exaltation of the circulatory and nervous systems – imparting increased vigour to the muscles as well as to the intellect, with an indescribable feeling of satisfaction.’ (Actually cocaine constricts the blood vessels, which is why sniffing it severely damages the user’s nose.)

‘The value of Coca Wine in conditions of debility is too well known to require comment.’ (A much used line in 19th century advertising, avoiding the need to give further details.)

‘Not a stimulant but a restorative nerve tonic for all complaints arising from depressed vitality.’ (It’s a stimulant, nothing else.)

‘Invaluable in cases of influenza, sleeplessness, anaemia, mental fatigue, &c. (For ‘&c.’, read ‘and everything’.)

‘Strongly recommended by the Medical Press and the highest Medical Authorities throughout the United Kingdom.’ (Older readers will remember the advertisements in which Craven A cigarettes were recommended by doctors.)

‘They [physicians] urgently recommend its use in the treatment of Anaemia, Impurity and Impoverishment of the Blood, Consumption, Weakness of the Lungs, Asthma, Nervous Debility, Loss of Appetite, Malarial Complaints, Biliousness, Stomach Disorders, Dyspepsia, Languor and Fatigue, Obesity, Loss of Forces and Weakness caused by excesses, and similar Diseases of the Same nature.’ (The ‘excesses’ may be understood to be sexual.)

‘Dose as a Tonic. One Wine-glassful before or with each meal. Children Half or Quarter of a Wine-glassful.’ (Hey, let’s get the brats hooked on this stuff early.)

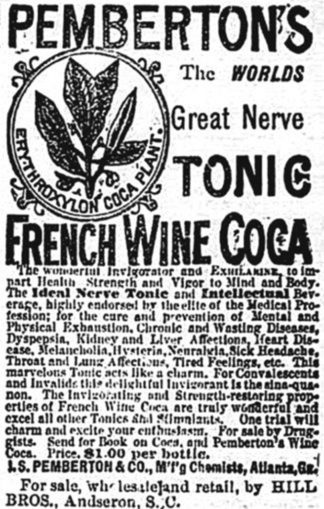

One of these imitations was Pemberton’s French Wine Coca, created by Colonel John Pemberton of Columbus, Georgia. He had been wounded in the American Civil War and treated with morphine to which he had become addicted, and he found that cocaine relieved the withdrawal symptoms. No one at the time considered that you might get addicted to this too.

Pemberton’s original advertisement left few claims unturned:

‘The wonderful Invigorator and EXHILARINE [sic], to impart Health Strength and Vigor to Mind and Body. The Ideal Nerve Tonic and Intellectual Beverage, highly endorsed by the elite of the Medical Profession; for the cure and prevention of Mental and Physical Exhaustion, Chronic and Wasting Diseases, Dyspepsia, Kidney and Liver Affections, Heart Disease, Melancholia, Hysteria, Neuralgia, Sick Headache, Throat and Lung Affections, Tired feelings, etc. This marvelous Tonic acts like a charm. For Convalescents and Invalids this delightful Invigorant is the sine-qua-non. The Invigorating and Strength-restoring properties of French Wine Coca are truly wonderful and excel all other Tonics and Stimulants. One trial will charm and excite your enthusiasm.’

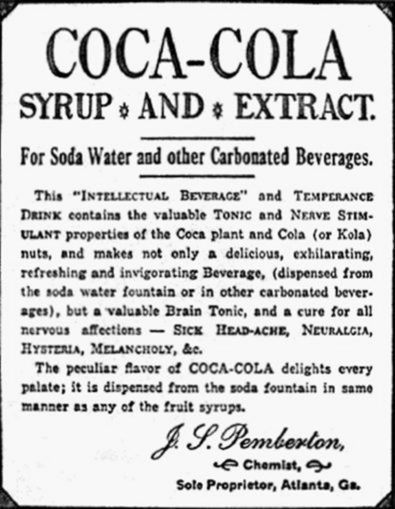

However, the growing American temperance movement soon hampered his endeavours when his district was declared ‘dry’ and the sale of alcoholic drinks banned (though cocaine was fine). Pemberton hastily reformulated his drink in a non-alcoholic version, and craftily marketed it not as a bottled tonic, but a syrup which could be sold to soda fountains in drugstores to be dispensed as a flavouring for fizzy drinks. He called it Coca-Cola. The second part of the name was due to its containing an extract of African kola nuts, high in caffeine and theobromine, both of which added to its stimulating properties. Each US gallon (128 fluid ounces) of syrup contained 5 ounces of coca, so that even when diluted with soda water it packed quite a punch.

Despite the extravagant claims of earlier decades for the benefits of coca, administrations eager to prevent enjoyment were closing in on it. In 1891 Pemberton reduced the coca content of his drink by 90 per cent, and in 1904 began to use ‘spent’ coca leaves from which cocaine had been industrially extracted, leaving only a trace of the drug. Today’s Coca-Cola still contains coca leaves but they have been totally decocainised. Bottled Coca-Cola dates from 1895. The familiar bulbous shape of the bottle is a representation of a kola nut.

The original Vin Mariani struggled on against increasing anti-drug legislation, but finally ceased production in 1914. Mariani himself died later that year. He had kept the formula secret, and it was lost with him. Other brands of ‘tonic wine’, which had no effect at all other than to make the imbiber pleasantly drunk, continued in production and are still with us – as, of course, are Coca-Cola and a host of imitations whose only common property is that they contain some source of caffeine to give a stimulating effect.

But that is not quite the end of the story. In 2014 Christophe Mariani, as far as is known not a descendant of the inventor, analysed surviving samples of the wine in an attempt to re-create it. The resulting beverage was marketed in 2017, still based on Bordeaux wine but now fortified to 22° for a more cheering effect – which was sorely needed, since to comply with current legislation it uses decocainised coca leaf. However, if you want to create the original kick of the famous wonder drink, there is nothing (except the law) to stop you from dissolving a line in your glass.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019. All illustrations are in the Public Domain.

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player