© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2019

‘I hope that you’ve all studied logical positivism?’

Incarcerated in Paranaque Municipal Jail, part of Metro Manila’s southern urban sprawl, it is boily hot and dark. Thousands of pairs of pin prick brown eyes look at me through the gloom and wonder if there are any valuables concealed about me. There is an escape plan which can’t be executed until the guard changes. In the meantime, I pray to God that distracting the other prisoners with a puzzle and a tale, works.

‘The Dabawenyos think I’m in Manila or Josephina. The Manilenos think I’m in Josephina or Davao. The Josehinyos think I’m in Davao or Manila. Where am I?”

Hearing some good answers, my recollection is jogged and the muses begin to formulate an interesting story to keep my fellow inmates occupied.

‘Prison.’

‘Utopia?’

‘The fire station?’

‘The Strip?’

Then the correct one,

‘Mister, you could be anywhere.’

‘Exactly, my friends’, I reply, ‘Let me tell you this….’

Fairly close to the centre of Manila is a sleazy district called ‘Ermita’, also known colloquially as ‘The Strip’. Even sleazier, a friend tells me, than the main roads next to the shanties close to the airport. There was a rhetorical commitment, led by bishops and politicians, to clean the place up. This never got much further than, the week before an election or Holy Festival, the whole place being very publicly closed down with, the week after, without any publicity at all, the whole place being opened up again.

Another friend tells me that cheap accommodations in the sleaziest part of Sleazeville were very basic, with slats where windows should be, sleeping mats on the floor (rather than beds) and no electricity (let alone air conditioning). Bring your own torch. Bathrooms consisted of a concrete floor and a tap. Such places were infested by insects, which at least had the decency to scatter when a torch beam touched them. Rooms slept ten. Prices were based upon sharing with nine strangers. No thanks.

Wanting to drop under the radar and also be reasonably comfortable, I would stay at ‘The Swagman’. Aimed at a particular type of tourist, it was branded with a large illuminated caricature of what a Filipino thinks an Australian thinks a cheeky swagman looks like. The Swagman in question wore a cowboy hat and had a crocodile tucked under one arm. A failing bulb for his right eye meant he winked knowingly at me every time I crossed the threshold.

Stepping into my room sent countless insects scattering under the bed but I did have aircon and a bathroom that even contained a working toilet. There was a proper window but its blind was pulled down tight and screwed permanently shut. Outside was the unmistakable noise of a family living next door, in an improvised wooden shack, using one of my bedroom walls as one of theirs. They chatted away amongst themselves in their native dialect while my aircon hummed and my television played away (even though it was switched off).

I lay on the bed reading a complimentary Manila Bulletin. The front page quoted a War Lord who’d promised to decapitate the Holy Father during his forthcoming visit and, for good measure, all other foreigners. The electricity went off and the room soon began to stifle.

I enquired at reception,

‘Brown out, sir’.

Stepping outside, the street, which had been busy to start with, was now packed with dozens of portable diesel generators, wires going everywhere. Office girls sat in the open, working away at their typing, often churning out the ubiquitous bio data sheets.

I walked around The Strip, relaxed enough in daylight, private security guards were dressed in dark blue and gold, American style, reassuringly named as ‘Yumyum Security’ or ‘Keeping You Safe Corporation’. The atmosphere changed at ‘lights out’, the very sudden tropical sunset, after which the streets glowed with gaudy electric signs. Girls sat outside bars while music belted away from within.

‘See you inside, Joe.’

‘Pay bar fine for me, mister.’

‘Can my bay-bee have your blue eyes?’

Being a church going, repressed prude, who is more or less tee total and makes a Scotsman living in Yorkshire look profligate, I’m difficult to blackmail, bribe or entrap. On the other hand, nights out aren’t a lot of fun. I headed back to The Swagman.

That’s what I told my fellow prisoners but as an aside I’ll tell you this. Now isn’t the right time to elaborate but suffice it to say, if the bar ladies were handled (behave) cleverly and innocently, they were an important source of information. More another time.

Making my way back to my room I passed a church. Inside, people in jeans and colourful tee shirts knelt in prayer. Outside, boys played basketball into a hoop on a telegraph pole, at the top of which was a festoon of spaghetti wire, tied in a mad Gordian knot, bundling utilities to neighbouring buildings. Held within them was a hand painted sign captioned ‘Say No to Abortion’, beneath an image of an unborn baby depicted as the Nino (the Christ child).

Back at The Swagman I didn’t get much sleep.

The (noisy) aircon had to stay on all night. The TV spoke even when switched off and turned down. Touts knocked on my door offering drinks and girls, likewise over the phone. Taking the receiver off the hook made it hum and trying to pull it out of the wall led me under the bed to those insects. I gave up. It quietened down. It got noisy again. The family sharing my wall stirred and began frying their breakfast. In truth, even if I’d been profoundly deaf and staying in a seven-star hotel I would have struggled to sleep, as the next day was going to be difficult. Lots to do.

Outside the Swagman there is a long but impossible-to-get-lost-on walk to the elevated railway, the LRT, but Manila in the rush hour still isn’t much fun.

A giant billboard sized pollution meter had been placed beside the main road for the encouragement of the careful driver. The day it was switched on, all the dials moved around to red and stayed there stuck. Heat and pollution welded the needles to the dials and then began to dissolve them.

Flocks of migrating birds would fall out of the sky having choked to death. Every bright yellow cloud of smog has a silver lining, your humble author didn’t need anti-malarials, as flying insects couldn’t survive. I’m not an expert, and the natives did tease me mercilessly, but when they told me that some streets were technically sterile, as even bacteria couldn’t live there, I believed them.

Synthetic fabric suffered too. It didn’t even have to rain acid. The chemicals dissolved in your sweat and then burned your clothes from the inside. In the days when such a thing was possible, a colleague arrived in a ‘shell suit’ which then began to fall apart. It stretched about on its own and began to lose its shape. Holes appeared in it. He sprinted to a department store, where they fitted him out in silk and cotton, fortunately for pennies. His legs were permanently tattooed in blue stains from the dye in the melting material.

From smog yellow, the air would turn green and then greener still, allowing the impressive Makati City skyscraper skyline to disappeared into it. As the sun rose, fresh clean air was drawn in from Manila Bay, across Corregidor island, over the squatter infested reclaimed land, past Roxas Boulevard and into Manila proper, refreshing the city. Thank God.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2019

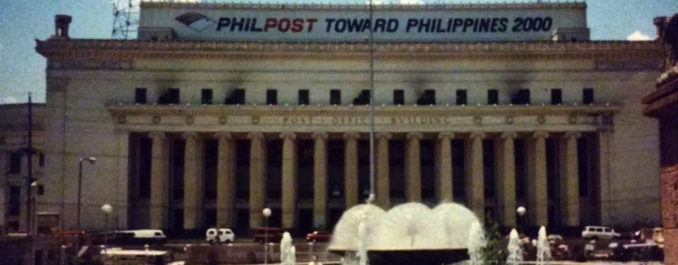

The LRT trains were very, very packed. There was a special carriage reserved for women and old people and a blind eye was turned allowing me to use it too. My first stop was the Post Office which was accessible from the LRT station via under passes, flyovers and by climbing over the traffic. The actual building is huge and built in the American colonial style with Greco Roman columns leading to a flat, stepped roof.

In front of the columns, a shanty town was being cleared, bulldozed rather, in anticipation of the Pope’s visit. Above the columns, on the first tier of the roof, was a giant sign proclaiming ‘Towards Philippines 2000’, signalling President General Ramos’s ten-year (ish) economic plan.

In its great dingy hall, rows of counter windows announced a bureaucracy promising to collect and deliver every combination and type of package to every combination and type of location. Surface to the Visayas, busy, airmail to Mindanao, busier still.

Elsewhere, a girl sat at her place and slept with her head in her hands (perhaps as her mother had before her?) on a marble counter behind a wrought iron grill. Above her, a faded sign pleaded for ‘Surface Packages to Belgium’.

‘Airmail from Great Britain & it’s Empire’ were holding a box for me. I showed my ID and relieved them of it. The old ladies, back in the mail room in London, had been kind enough to print OHMS in giant letters on its top left-hand corner. I winked at the girl explaining,

‘On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.’

She opened a desk top grate and passed it through. It was pizza box sized and shaped. I tucked it under my arm and made my way back through the shanties to the LRT station, crossed the mighty Pasig River, and alighted at the next stop which is Quiapo, a much poorer part of the city and very congested even by local standards.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2019

Around Quiapo church was a giant public market whose narrow streets were narrowed further by stalls and hawkers. The scene was appropriately biblical. The square before the church thronged. In the gutter, children sold rancid water from old plastic bottles. Local brews were vended in plastic bag with straw. Old ladies sold re-used bleached sanitaries, one at a time, from tables. Some of the traders had their wares draped around their necks, including lucky potions, charms and abortifacients.

The church itself was so full that I couldn’t enter. A flow of faithful pushed me towards a side street. Within the church is a near five-hundred-year-old figure, the Black Nazarene, which is carved as if the humblest outdoor Pinoy worker, carrying the crucifix, dark skinned.

This miraculous one brings hope to difficult lives and can heal the sick. The church was a place of devotion for suffering, loss and for ‘intentions’ when faced with the worst of times, a place for the dying, dead or killed. The unborn dead were sometimes wrapped in a bag or paper and left on the church steps as if returned to God unwanted.

Pushed through the side streets, I was now lost and would pray for the fallen as best I could while orientating myself, still clutching my now battered box.

In a slum area, I was further diverted by road works and a street blocked off for a local festival. Plastic bag bunting was strung across the roads which were now, thankfully, so narrow that all was in shade. Some light was provided by a man welding car axle raised on bricks. Children played among the sparks.

The buildings became older, all wooden, faded and pitted to black, shutters jammed, verandas draped with drying washing. The place stank. Holes in the road showed sewers packed solid with stagnant waste. Old, broken, young men, staggered along the sidewalk. They shook and were emaciated, their heroin eyes and veins bulging. Loose rags hardly kept decent their living dead frames.

Very lost, I fell across the fire brigade. Wary of uncontrollable fire in the packed wooden streets, appliances were often placed in clearings in the slums. I told them my destination. They typed it into a keyboard, gave me a print out and, sooner than I had hoped, I had found Santo Tomas University and refreshing tranquillity beyond the busy roads.

Before the main building is the verdant green lawn of Asia’s oldest university. I walked part way across, stopped and bowed my head. In silent reflection, I imagined back the years, seeing this place as a shanty during the Japanese occupation. All of Manila’s internees, British and other, had been concentrated here. Many perished, never seeing beyond its wires and guard posts again. The Filipinos had paid a price too, both during occupation and liberation.

Being hill and lake men, my local regiment, including family members, served in the Far East. Not all of them came back. Those that did never spoke of it. Others, and others from your place too, were at Singapore when it fell or on the Prince of Wales or Repulse when they were lost. I opened my package, took out it’s poppy wreath and laid it on the middle of the lawn. It was 15th August, VJ day.

We remember them.

Liberation, men at Santo Tomas US Army Signal Corps – Public Domain

To be continued….

© Always Worth Saying 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file