Fellow Postaliers, imagine that you fire up your computer in the morning, open the Daily Express website to check the headlines and find yourself looking at your own swooningly handsome visage, in a row of big mugshots. Complete with your name and town of residence, under a headline reading “Here are the haters of Going Postal.”

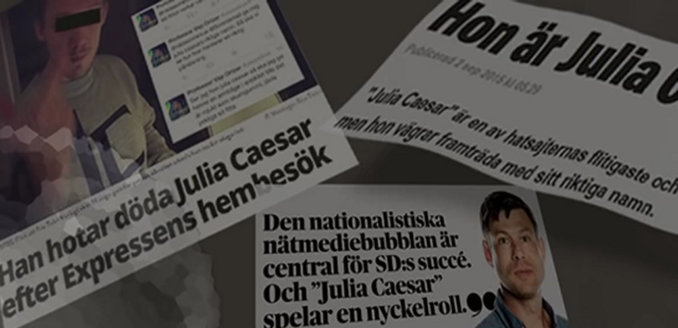

Well, if you are Swedish, you don’t have to imagine this scenario. Because it really happened. On December 10, 2013, the tabloid Expressen filled its online front page with eleven face photos under a headline that read “Online haters on Avpixlat” each of which was accompanied by a tell-tale caption. Avpixlat was a Swedish version of GP; it has since been restructured. Included among Expressen’s targets was a Mikael Rahm (Sweden Democrat politician), who remarked, “It is already the eleventh hour when it comes to stopping the idiocy that comes with Islam, which is foreign culture to us .. Islam is not a religion, but a sick cult and should be classed as such.” For these pungent sentiments, which are quietly shared by millions, Rahm had to step down.

Expressen had got the private details by using a snooping agency founded by former “revolutionary” socialists called Researchgruppen. The Swedish media’s doxxing war against dissidents has continued in the intervening years, using the same quasi-legal methods. Of its victims, some lost their jobs and one is rumoured to have committed suicide.

* * *

Most victims of doxxing disappear and lie low after their humiliation. But in 2015, it was the turn of one of Sweden’s best-known bloggers, Julia Caesar, to be “hung out,” as the Swedish term has it. Her case was different.

Julia Caesar, a former journalist on a leading Swedish daily, wrote regular columns on the Danish website Snaphanen (several Swedish writers are forced by censorship in publish in Denmark). She is a gifted commentator who covers the issues familiar to readers of this site—freedom of speech, the dangers of Islamisation, mass immigration. Her style and tone are moderate and considered. She has an unusual ability to explore complex issues using simple, telling language, and has a sizeable, though not huge, following. I have based an article of my own on one of her blog pieces A reason for reconsidering support for the Red Cross. Julia Caesar—I’m not going to give her real name but it can be googled easily enough—did not bolt down her rabbit hole when she was doxxed. She talked, wrote and broadcast herself about the experience. She became a news story, and was discussed in the broadcast media.

She talked about it all in a couple of Swedish-language podcasts released in 2016:

“This is my account of how it is to be in the middle of a media smear campaign, to be exposed to storms of hate. This is what it’s like not being able to stay at home, to be sleeping in different places each night, with a police alarm [device] as your only security … Journalists understand how to destroy people’s lives and it is a power that they are happy to use ..”

Julia Caesar was doxxed by two journalists working for Expressen and the somewhat higher-brow Dagens Nyheter, Annika Hamrud and Niklas Orrenius. Her ordeal began when Orrenius one day knocked on the door of her cottage out in the backwoods, where she lived alone. This was at the height of the Syrian migrant influx, which had created a sanctimoniously febrile atmosphere in Sweden—in her words, a “mass psychosis.” When she refused to answer, he just stayed there knocking on the door and calling out her name. The fact that he knew her name told Julia Caesar that she was about to be doxxed. “I understood too what that meant: the risk of being exposed to violence and threats.” She suffered four of these unwanted visits in all, at her two addresses.

Orrenius, from Dagens Nyheter, said he wanted to “talk.” He had sent no email or letter in advance. When he got no answer, he questioned neighbours. He returned with a photographer, who stared aggressively in through the window, his face pressed against the pane, while Julia Caesar was on Skype. “Both men stood outside and shouted into my home for 30 minutes. This is well-known gangster behaviour. We know who you are, we know where you live… When I began to write chronicles on the Snaphanen website, I wanted to protect my own security and that of my nearest and dearest. My security has been smashed to pieces. The second time they came, I was shaking all over. I felt extremely exposed and defenceless.”

Her identity was made public in September 2015, “with name, pictures and details of my medical conditions,” by Expressen, which Dagens Nyheter had tipped off. Soon, she was receiving death threats, by email and in the morning post: “Nobody missed the opportunity to spew out their hate.”

Julia Caesar is not a Katie Hopkins figure, ready to confront and tongue-lash anybody who oversteps the mark. She is, in the words of blogging journalist Marika Formgren at the time Marika Formgrens blogg, “a 70-year-old disabled woman with heart problems, who after a long career as a journalist chose to write under a pseudonym to protect her children and grandchildren and herself from threats that were anything but imaginary … Being exposed to such a shock and severe stress could actually kill a sick senior citizen. Did Dagens Nyheter take a calculated risk? Is [editor] Peter Wolodarski so blinded by his quixotic fight against “internet hate” that he thinks the life of 70-year-old woman is a negligible sacrifice? What would he have said to her children and grandchildren if he and Orrenius had stood there with her blood on their hands? ‘Sorry, but she was an online hater. In the fight against online hate, all means are permitted?’”

In one of the podcasts, Julia Caesar slowly and punctiliously lists the insults heaped on her on different websites, of which I record here only a few that were not obscene (I didn’t understand the rude ones anyway): paranoid, psychologically sick, delusional, weak-minded, conspiracy theorist, workshy benefit scrounger, racist, sociopath, devil, fascist. That, she states, is just a small selection of the invective from “people who do not know me, who have no idea who I am, and who had never read a line of anything I have written.”

She was doxxed, she says, because, unlike many other public figures who need to be silenced because their views “threaten basic values,” there was no other point of attack. She was a problem for the Swedish left, which wanted to make an example of her. But she did not have any job or party membership that she could be expelled from, nor were critics able to dig up any scandal dirt on her. She was already an outsider and a retiree, so there was no pedestal she could be knocked off. Nor could she be portrayed as a basement storm-trooper with swastikas on the walls. She was an elderly lady who chose her words carefully, a voice other women could identify with in an arena dominated by angry middle-aged men. And she was persuasive.

Doxxing was all that was left. The publicising of her medical records was intended, she says, to cast doubt over her mental capacities, and make her seem a “non-person.” Julia Caesar also believes there was an element of revenge-taking too, since she had used her deep knowledge of Swedish journalism to attack certain purveyors of fake and biased “news.”

* * *

Her remarks on the psychology of this disgusting, cowardly tactic are fascinating. She sees herself as a victim of a 21st century witch-hunt, or as a kind of lightning conductor for the force of hate that is always present in a population, and always seeks an outlet.

“From the beginning of time, people have had different strategies to smear and ostracise people who diverged from prevailing norms. They are often described as evil, fit only for punishment. In the 17th century, more than 30,000 witches were burnt. Behind the persecution was the church. The witch trials of our times are the media smear campaigns.

“Guilt and shame have always been tools for social control … Just as in the past .. the victims shall be exposed as publicly as possible. You don’t actually need to have done anything wrong to become the victim of a media smear campaign.

“Journalists are supposed to scrutinise power, but increasingly, what they scrutinise is people. The truth becomes the first victim of a smear campaign, and instead of critical scrutiny, you have persecution of the individual. For journalists, it is a matter of irrelevance whether the victim of a smear campaign has actually done anything wrong. Although more than 30% of journalists in Sweden are women, [they say] feelings are not something you talk about. The media believe that smear campaigns have a higher goal, namely to uphold social morals, so they develop strategies to justify what they do.” Hence, “the harm that they cause is ‘inevitable,’ and the sufferer is no victim; rather that person deserves to be treated like this.”

There is much more I would like to reproduce from her two podcasts on this subject, but this article is long enough already. I will just end this part by noting the ironic upshot of Julia Caesar’s doxxing. It’s popularly known as the Streisand Effect. Only 7% of the Swedish public knew of her existence before it happened, she says–“so much for my being an influential opinion former.” But the number rose to 55% after her doxxing.

Julia Caesar describes these experiences in more detail in her Swedish-language article Mardrömmen (The Nightmare).

For Joe Slater’s free downloadable pdf travel books on Sweden, North Europe and East Asia, please visit this website: iTabibito.com

© Joe Slater 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player

срочный займ менимен займзайм на карту на годкак взять займ займ денежных средствзайм денег на кивизайм под залог недвижимости в краснодаре