October 18th, 1809.

Fred goes up before the judge at the Old Bailey tomorrow, accused of the murder of poor Mr Armitage.

We visit him daily in his cell, bringing bribes for the gaoler and food, drink and news for him. He has been a guest of His Majesty before, though never remanded on so grave a charge, and does not complain. It would be wrong to say that he is confident, for so rotten is the edifice of justice that even the utterly innocent have reason to fear that the roof will fall in and crush them. Yet, as the old adage has it, Fiat justitia, ruat coelum – Let justice be done, though the heaven fall.

We have not been idle in his defence, and he has that to comfort him. On the advice of Mr Bundle the solicitor, seconded by Jem who has also had his brushes with the law, we have engaged a barrister by the name of Quintus Heron. Seldom was a man so aptly named. He is tall, grey and skeletally thin, with a sharp beak of a nose and cruel pale eyes. His speech is laconic and rasping, and when he is amused he emits a harsh screech of laughter that would curdle milk. As Jem said, ‘I don’t like ’im much. But ’e ain’t ’ere to be liked, ’e’s ’ere to do damage to them bastards, an’ I believe ’e will.’

When Jem is not playing his flute in the orchestra he has usually been absent, and has often returned late. During these excursions he has been wearing clothes much more shabby and soiled than his usual attire, and on the following day he has had a long conference with Mr Heron. He will not tell me what the two have been plotting: ‘Better yer don’t know, Daisy me dear.’

October 19th, 1809.

We closed the theatre for the day of Fred’s trial. We could do nothing else, for we were all too racked with nervous strain to perform. Signora Catelani has been in floods of tears, and we are doing our best to comfort her.

What a sad reverse after our triumph! But we cannot protect ourselves against misfortune. In the words of Phocylides, Κοινὰ πάθη πάντων· ὁ βίος τροχός, ἄστατος ὄλβος – Suffering is common to all: life is a wheel, and good fortune unstable.

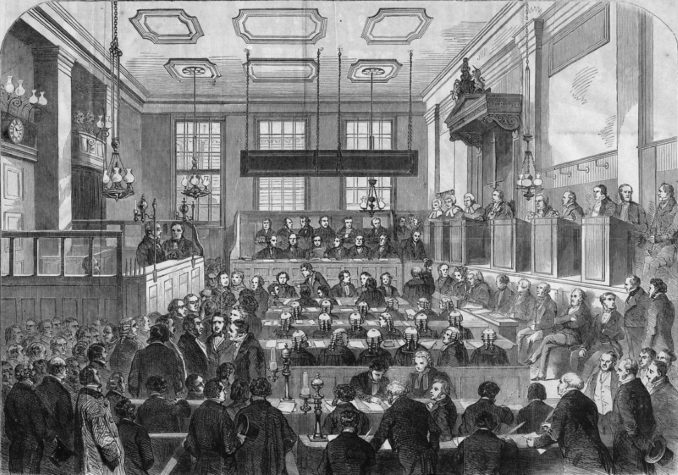

We arrived en masse at the Old Bailey. No one made any protest when nine bears took their seats in the public gallery – we are now part of London life, and even the boys who sweep the crossings salute us as we amble down the streets.

The proceedings opened with the ancient and terrifying call on ‘all persons having to do before the lords justices of oyer, terminer and general gaol delivery to draw near and give their attention’. Oh, they had our full attention, and we were as eager as a pack of foxhounds to find justice. Our judge, Isaiah Gaunt, belied his name – plump, rosy-faced and sleepy-looking. We all prayed that we would stir him to wakefulness.

Fred was brought in between two hulking officers; he looked shrunken and exhausted, and my heart went out to him. For the first time I noticed that he had a few grey hairs. After he had pleaded Not Guilty, we had our first sight of the counsel for the prosecution, one Lucius Pike, a long slimy snaggle-toothed streak of a man who, were it not for his horsehair wig, would look at home in Mendoza’s gang. Would our own Mr Heron be able to spike him?

As we expected, Pike’s first witness was one of Mendoza’s men, who gave his name as Ananias Oates. Under oath – and the Bible must have seared his hand to the bone, though he gave no sign of it – he testified that he had seen the accused strike Mr Armitage on the head with a piece of wood, ‘mebbe the leg o’ a table’.

It was now time for our champion Quintus Heron to enter the lists and cross-examine the witness. His first question was as sharp as his nose: ‘Mr Oates, is it true that you have two previous convictions for perjury?’

Pike, of course, objected that the character of his witness was immaterial and that he was under oath, a vain plea in view of the accusation, and as Heron probed Oates further about his convictions for affray and grievous bodily harm it was clear that he was holed below the waterline and sinking fast. Hope began to grow in all our hearts.

Pike’s second witness, one Mucius Slider, was also one of Mendoza’s crew. He gave evidence of much the same story – and in almost the same words. I had my eye on the jury, and it was plain from their demeanour that they were thinking much the same as myself.

We all silently cheered as Heron demolished him in the same manner as he had done with Oates. But our fearsome advocate had one further blow to deliver: ‘While I would never suggest that you were paid by Mr Kemble to attend this occasion, might I ask you why you happened to be in Oxford Street at this time?’ This fine example of apophasis brought Pike spluttering to his feet, and the judge ruled in his favour, but a glance at the jury showed that the shot had struck its mark.

After Heron had dismissed a third witness, Ahaz Mugger, with equal brusqueness, we were beginning to believe that we had the enemy on the run. There was no doubt that the prosecution could call on any number of ruffians who would perjure themselves for a pittance, but it was equally sure that our advocate had their measure; and no more of them were called.

The next witness was a handsome lady of thirty or so, fashionably dressed and of genteel deportment. She gave her name as Hesperia Fairbrother, widow of the late Sextus Fairbrother of Rankling Hall in the county of Essex, and testified that she had been waiting outside the theatre before attending the performance of La Vestale.

‘I trust, Madam, that you were not injured in the affray,’ insinuated Pike.

‘No, Sir, not in the slightest,’ she replied. ‘But I saw the whole affair unroll before my eyes, from start to finish.’ And then she made the now familiar claim that Fred had started an attack on innocent bystanders, and she had seen him strike Mr Armitage on the head with a wooden club.

During her testimony I saw Jem consulting in whispers with Heron and leaving the court rapidly.

It was now time for our man to cross-examine the witness. He began, ‘Mrs Fairbrother, I am truly glad to hear that you escaped harm in this unhappy incident. I trust that you were able to attend the performance.’

‘I was, Sir,’ she replied, ‘and was greatly diverted by the spectacle.’

‘It is a remarkable entertainment,’ said Heron. ‘The scene in which Jupiter descends from heaven on a cloud is particularly well contrived.’

‘Just so; I was much moved by it,’ she said, but was then interrupted by the judge: ‘Mr Heron, would you kindly confine yourself to the facts of the case.’

‘My apologies, your Honour,’ said Heron. ‘Mrs Fairbrother, since you viewed the entire incident, would you please tell us what the accused was wearing at the time?’

‘He was dressed much as I see him now,’ she said, ‘in a brown coat.’

‘Can you describe his breeches and stockings, madam?’

‘I recall that the breeches were black, with white stockings.’

Mr Heron then asked for Fred to be allowed to step out of the dock for a moment, and it was apparent that her description of his nether garments was perfectly accurate. Pike looked pleased – but I knew that he was taking a bait.

There were no more questions. The prosecution rested its case and the court adjourned for luncheon. We passed the time in a coffee-house, uneasily aware that we needed to keep our wits about us.

We returned to see Mr Heron present the case for the defence. His first witness was none other than Mrs Armitage, the widow of the deceased – perhaps it was surprising that the prosecution had not seen fit to call her. She was a trim lady in her forties, dressed in unrelieved black, her comely countenance ravaged by weeping.

After offering his sympathies with a sincerity in which I would have believed had he not been a lawyer, Heron asked her for an account of the evening on which her husband had met his sad end.

Dabbing her eyes with a small lace handkerchief, she explained that she had not been able to attend the performance herself, as she had been looking after her little daughter who had the measles, but that she had urged her husband to go to town without her. ‘Alas, would that I had advised him otherwise,’ she gasped between sobs. The jurors were visibly affected, and one of them had deployed his own handkerchief.

She recounted that Mr Armitage had returned in his carriage in good spirits, having enjoyed the opera and making light of the wound on his head – ‘a bit of trouble with the usual theatre mob’ – but that he soon complained of a headache. A glass of restorative brandy had no effect, and he took to his bed, which caused no great disquiet at first, but he was fated never to leave it alive.

‘Did Mr Armitage describe his assailant?’ Heron asked.

‘Indeed he did – a tall heavy-set man in a soiled linen short and ragged breeches. After he had struck my husband’ – she paused to wipe her eyes – ‘one of his companions said to him, “Leave ’im be, Dan, ’e ain’t worth yer trouble.”’

I was beginning to see a plan unfolding. Pike did not cross-examine her.

Heron thanked her, I think with genuine gratitude, and said that he hoped it would not be necessary to trouble her again.

The next witness was someone I had never seen before, a thin, pale, red-haired girl of no more than twenty, shabbily dressed. She gave her name as Dolores O’Connor.

‘Thank you, Miss O’Connor,’ said Heron, ‘for attending the court at such short notice.’ She smiled thinly. I realised that Jem had found her during our recess for luncheon.

Heron asked her where she had been at 6 o’clock on the evening of the murder. She had, she said, been sweeping the courtyard at the back of the opera house.

‘Which opera house was that?’

‘Why, the one at Covent Garden, o’ course. I were workin’ there till today, when that Mr Kemble sent me away. ’E said ’e was makin’ economies, ’cos ’e was losin’ money what with the riots an’ that Bear Theatre drawin’ away the patrons. But I lost more ’n that, ’cos I ain’t got no work no more.’

‘On that evening, did you see anyone going through that courtyard?’

‘Yes, I seen that Mendoza an’ ’is pals goin’ out. I thought as ’ow they was off to deal with the Old Price crowd agin.’

‘Can you see any of those people in the court now?’

‘Yes, I can see that Ananye an’ Ayaz an’ Mucie sittin’ over there’, and indicated the prosecution witnesses, who twitched as her finger pointed at them.

‘And at the same time did you see anyone coming into the courtyard?’

‘Yes, that Mrs Fairbruvver – I can see ’er next to ’em now. She’s a – um – lady friend o’ Mr Kemble, an’ often comes to see ’im of an evenin’.’

‘Did Mrs Fairbrother stay long?’

‘I didn’t see ’er go, an’ I was in the yard till nine at least.’

Pike, cross-examining, tried to suggest that she was prejudiced against Kemble because she had lost her employment. Her reply was simply, ‘Sir, I’m on oath, an’ I’m ’ere to say what I seed, an’ no more.’

The next witness was myself, a matter which caused some difficulty. Pike objected that I was not a ‘person’ within the letter of the law.

Heron replied, ‘Sir, we are taught that God has three persons, and only one of them has been a human being.’

To which Pike retorted, ‘Are you suggesting that the Lord is a bear?’ As laughter resounded through the court, I thought, I do hope so.

The judge, intervening, said that he would accept evidence from any creature that could prove itself to be rational. A school blackboard on an easel was brought into the court and set up beside the witness box so that the judge and jury could see it.

I took the chalk and wrote, Your Honour, I am a rational bear and I am ready to be sworn in.

Pike objected, ‘How can a bear swear an oath? We know that brute beasts have no souls.’

I wrote, I do not know whether I have a soul. But, like Pascal, I will bet that I have a soul, and I will follow the Lord’s commandments that my soul may be saved. If I die and have no soul, I will have lost nothing. But if I have a soul, God willing I will gain Heaven.

‘She cites Pascal! That is enough,’ said the judge. ‘Daisy, you may lay your paw on the Bible and then write the oath on the board.’

I swear to Almighty God that I shall tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

Heron then asked me to recount what I had seen. Wiping the board clean to make space, I wrote that before the play I had been outside the theatre, making sure that the people waiting for tickets were lined up in an orderly manner. I had seen a mob coming along Oxford Street and, fearing a commotion, I had gone inside to summon the other bears.

‘Where was Mr Rowland at this time?’ Heron asked.

He was inside the theatre selling tickets.

‘Did he come out at any time?’

Only after the disturbance was over. Then he helped those who had been injured into a lower room in the theatre, and offered them free tickets to the opera to compensate them for their maltreatment.

‘Can you tell me how Mr Rowland was dressed at this time?’

He was wearing his usual clothes for these performances: a black coat and black pantaloons reaching to the ankle in the new style.

‘During the disturbance, did you see anyone strike the deceased?’

I saw a mob armed with wooden clubs assault our customers without the least provocation. In the crowd, I could not see who was being struck, but among the assailants I could see Messrs Oates, Slider and Mugger, all of whom are in this court – I extended a paw to indicate them – and also Mr Daniel Mendoza, who is not present today.

Pike was on his feet, spluttering, ‘This is hearsay evidence, Your Honour, and without confirmation.’

The judge asked, ‘Mr Heron, can you substantiate these allegations?’

‘I can, your Honour, and my next witness shall demonstrate their truth.’

Pike did not try to cross-examine me: I think he was afraid of what I would write on my board for all to see. The next witness was someone I had not seen before, or at least had not noticed: a Mr Roylance Allman, who had been among those waiting outside the theatre to buy a ticket. His testimony exactly matched my own, with the addition that he had been struck by Daniel Mendoza himself, whose face is well known to the public after his career as a prizefighter.

In his final speech, Mr Heron was at pains to point out the inadequacy of the evidence of the prosecution witnesses – he did not utter the word ‘lies’, but it was there, hanging in the air for all to see. He pointed out that Mrs Fairbrother had ‘misremembered’ the details of Fred’s clothing, and that she could hardly have attended the performance, as there is no scene in which a god descends. He offered to show the jury the libretto of the opera, which they declined. We were feeling modestly hopeful when the jury retired, and the court adjourned.

They were back within ten minutes, though it took another ten for the returning crowd to settle down and take their places. I noticed that Oates, Slider, Mugger and Mrs Fairbrother were not among those who came back.

‘Members of the jury,’ said Mr Justice Gaunt, ‘have you considered your verdict?’

‘We have, Your Honour,’ replied the foreman. He was looking most uncomfortable, as were they all, and said no more.

‘Out with it, man,’ said the judge.

‘Your honour, we find the accused … guilty … of murder.’

A gasp of horror resounded through the crowded court. Even the judge was visibly astonished. ‘And is that the verdict of you all?’

‘Er, it is, Your Honour.’

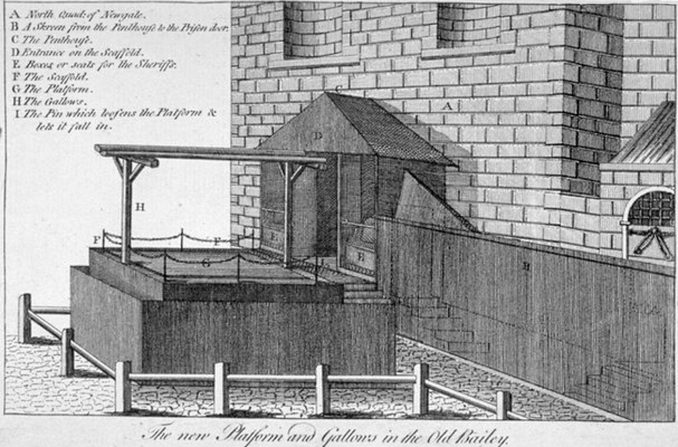

Directing a contemptuous glare at the venal wretch, the judge reluctantly reached for his black cap, a little square of silk resting on a cushion, and laid it on top of his full-bottomed wig. He said heavily, ‘Then I have no other course. Prisoner at the bar, you have been found guilty of murder. The sentence of the court is that you shall be taken from here to a place of execution, and there hanged by the neck until you are dead.’ He looked regretfully at Fred, who had collapsed against the wall of the dock. ‘And may the Lord have mercy on your soul.’

Fred, barely conscious, was carried out of the court by two burly officers. We could hardly stand ourselves, and reeled into the street.

Jem was the first to rally. ‘Me dear ole bears,’ he said. ‘We all knows the jury was nobbled. It ’appens. But we ain’t ’avin’ this, no way. We’re agoin’ to get ’im out.’

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player