July 15th, 1809.

After our success at Carlton House it would be tempting to expect offers from impresarios of the leading London theatres eager to stage our performance. But we have been – bears and men alike – too long in this uncertain business to imagine any such thing.

Fred has, after some searching, found us a place on the bill at Crint’s Theatre, a small and shabby establishment in Percy Street, which runs between Charlotte Street and the Tottenham Court Road. It has been converted by knocking together three rooms in a house hastily erected 120 years ago by If-Christ-Had-Not-Died-for-Thee-Thou-Hadst-Been-Damned Barbon – son of the hellfire preacher Praise-God Barebones, or Barbon – who preferred to be known as Nicholas but his acquaintances called him Damned Barbon. (He had no friends.)

Built without foundations, it has subsided badly, and going up the sloping and irregular stairs is an adventure. But I digress.

The proprietor of this establishment, one Jim Crint, does not inspire confidence. As Fred said, ‘We need to keep a close eye on this cove.’

Our place in the evening’s entertainment falls between a display by some acrobats calling themselves the Ravioli Trio, though they are actually from Bermondsey, and a recital of patriotic songs by a Mrs Minion, a lady of Greek origin disguised in a ginger wig but touchingly loyal to His Majesty (may he recover from his sad affliction). We have shortened our performance to half an hour, retaining the most exciting elements, and the drummer of the theatre orchestra has been equipped with two large wooden slapsticks to render the sound of gunfire when required.

July 20th, 1809.

Our first week has gone well, and the audience has been generous with applause. We now remain on stage flanking Mrs Minion as she sings ‘Hearts of Oak’, ‘Rule, Britannia’ and other favourite ditties, and she admits that her moderately melodious warblings are now much better received than formerly. We expect to be paid on Friday, tomorrow, after the performance. Fred and Jem will be accompanied by all the bears in case Mr Crint should be thinking of defaulting on his obligations.

July 21st, 1809.

Sad to relate, things have not gone as we had hoped: as Homer so wisely remarked, Ἀλλ’ οὐ Ζεὺς ἄνδρεσσι νοήματα πάντα τελευτᾷ, But Zeus does not fulfil all the desires of men. The evening’s performances began as usual, and we were waiting in the wings for the Raviolis to finish. They are two men and a woman, the brothers Albert and Arthur Yallop and Arthur’s wife Georgina, and much of their act consists of throwing Georgina from one man to another.

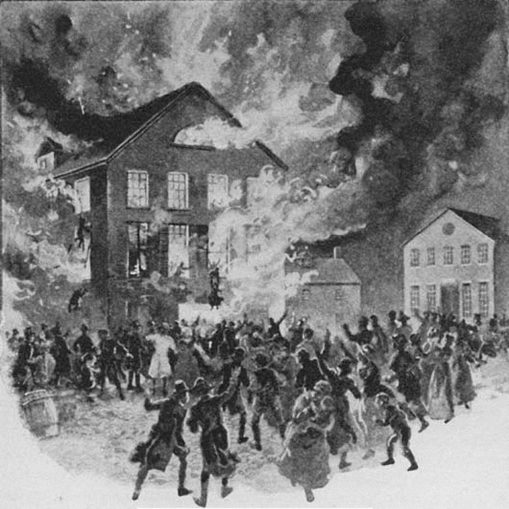

At the climax, Georgina was expected to perform a triple somersault in the air as she flew across the stage. But she mistimed her flight and struck Albert in the face with her foot, and they both went sprawling down on the boards, knocking over two of the Argand lamps at the front of the stage which provided illumination for the spectacle. In a moment the hem of her gauzy skirt went up in a blaze. Albert ripped it from her and threw it into the orchestra pit, where it ignited a pelmet hanging from the front of the stage. As the orchestra fled, the flames spread up and soon the curtain on one side of the stage was alight.

As you would expect, the audience fled towards the exit at the other end of the hall – only to find that Mr Crint had locked the door to prevent people from sneaking in without payment, and he and his keys were nowhere to be found. In the panic-stricken press, soon people would be trampled to death. But then we heard the voice of Fred, standing on the blazing stage and shouting, ‘Make way for the bears! They’re comin’ to break down the door!’

We surged into the hall and the people parted before us like the Red Sea before Moses. It was the matter of a few moments to kick through the panels of the door and wrench the frame to pieces, and the audience spilled out into the street.

Outside, smoke was billowing from the windows and a crowd had already gathered, to watch the spectacle rather than to help extinguish the blaze. It goes without saying that the economical Mr Crint had not paid for fire insurance, which might have provided an engine in time to save the house.

As we stood there, another voice was heard: ‘It was them bears what done it! Them bears started the fire!’ It was the voice of the infamous Crint, who must have escaped through the back door. Most of the crowd had no idea what had happened in the building, and in a moment the mood turned ugly. As people started to shout ‘There’s the bears! Get the bears!’ Fred and Jem appeared at our side.

‘Time to go,’ said Fred. ‘Daisy, form a square.’ We had seen enough battles to know what to do. The eight bears closed around the two men, and we marched out roaring terribly until we were at the edge of the crowd. There we broke ranks, ran up Upper Rathbone Place, and escaped through a little alley into Newman Street, from where we were able to proceed undisturbed.

The Italian boys had vanished as if they had never been. ‘Can’t say as ’ow I blames ’em,’ said Jem. ‘It was turnin’ right ugly back there.’

It was a relief to be back in our mephitic stable in Kensington. But Fred summed up the feelings of us all: ‘We can’t stay ’ere any longer, me dears. No more time ’angin’ around royals an’ nobs. It’s back on the road for us.’

July 23rd, 1809.

We have left London on the Bath Road, with no idea of where we are going and simply because it was the nearest main thoroughfare to our quarters. By common consent we have abandoned our former act and are simply dancing to entertain the audience. A performance in an inn at the peaceful village of Heathrow brought in the disappointing sum of £3 6s 4d, but this hardly matters, as our travels have taught us to live off the land and we need money for little more than to buy powder and lead to make bullets.

In search of better territory we turned off the main road to the south, and at the moment we are encamped in a barn outside the town of Guildford, and have been considering our future course. Fred was impressed by one of the artists at Crint’s Theatre, who conducted a mind-reading act under the name of The Great Mentalist, though he was actually called Saul Dunnock.

Mr Dunnock worked with an assistant, his wife Rachel. The stage was divided with a solid and perfectly genuine partition, which sceptical members of the audience could examine on request. They would come on stage and hand any article to Rachel, who would ask her husband, on the other side of the partition, what it was – and he would make his answer to her and the audience, almost always correctly.

The secret, of course, was in the words she used. There are a thousand ways of asking ‘What do I have here?’ and they had worked out a code to describe all the things that people in the audience would be likely to have in their pockets and bags – coins, pens, knives, combs, books and the like. For example, ‘What do I have?’ meant a house key, ‘What is this?’ meant a Bible, and ‘What am I holding?’ meant a watch. If you added ‘here’ to any of these it signified that they were large, but ‘in my hand’ meant that it was only part of an object.

July 25th, 1809.

Fred could remember only a small part of the elaborate code, but that did not matter, as every pair of performers must have their own private language and learn it by constant rehearsal. Of course I am playing the role of the Great Mentalist, and writing the answer with chalk on a board. I am to be Daisy the Discerning Bear, and we hope that the novelty will be well received.

We have been practising in every spare moment, with some success. Meanwhile our gallant band sustains itself by capering about in inn yards, shooting rabbits and wood pigeons, and scrumping early apples from orchards.

July 28th, 1809.

We are now at Farnham in Surrey, and this evening we tried out our new act publicly for the first time at the Queen’s Head inn. It went very well, for if you do not know how it is done, the spectacle is genuinely amazing. I successfully named a purse, a lead pencil, a watch case without a watch (‘What am I holding in my hand?’), an onion and a fan.

Then I sensed that Jem was in trouble. After a pause, which he disguised by sneezing and blowing his nose, he asked awkwardly, ‘Tell me what’s this odd thing ’ere what I bin given?’ ‘Tell me’ meant that the thing was not on the usual list of objects. ‘Odd’ meant ‘made of wood’, ‘here’ that it was large, and ‘given’ that it was long. From that description I could not guess much, so I wrote on the board ‘A big long piece of wood, but I know not what it is.’

There was long and loud applause, and Fred held the thing up for me and all to see. I recognised it as a weaver’s shuttle, but half the audience would not have had the least idea what it was. Sometimes a near miss can be better than a hit. And, as Periander remarked, μελέτη τὸ πᾶν, practice is everything.

Our evening’s collection amounted to the goodly sum of £15 7s 1d, as well as a small silver coin depicting the Goddess of Liberty with flowing hair. It was an American ‘half dime’ – the word comes from decem, ten, and a dime is worth ten cents and a half dime five. We shall keep it as a token of good luck.

August 5th, 1809.

It goes without saying that all the other bears, encouraged by my success, are eager to pursue specialities of their own. My dear son Bruin has ambitions to be a fire-eater, and has been practising this art for several days. His fur is now slightly singed in places, but he assures me that he is getting the way of it.

We found an old zither going cheap in a curiosity shop in Farnham, and Angelina is learning to play it. This instrument is very suitable for bears with their rows of strong claws, though we struggle with the violin or the hautboy. She can already mange two Portuguese dances and a passable rendition of ‘God Save the King’. She practises assiduously and I am sure that her skills will improve daily.

Jem found a discarded handcart in a rubbish heap, and took its wheels and has used them to make a small Velocipede for little Henry. It is not a difficult device to master, and on a smooth surface he can now ride it while standing on the saddle. There is the germ of an impressive performance here.

William believes that he can learn sword-swallowing, and has been experimentng with an officer’s dress sword – that is, a sword with a fine gilded hilt and a length of plain metal in place of a blade – which we found in the same shop. This is not an easy skill to learn, and much retching has been heard on the outskirts of our encampment, but he has been saved from injury by the bluntness of the sword and I am sure that his efforts will eventually be crowned with success.

Mary has been teaching herself to juggle. She can already keep four pine cones in the air.

Emily and Peter have been working on a seesaw performance, though this has had to be set aside for the moment after the builder’s plank they were using snapped under their weight. No matter, we shall find another.

Fred has been trying to think of a name for us, but after much cogitation has not been able to do better than ‘The Amazing Bears’. And why not? We are boldly going where no bear has gone before. As Ovid said, Audentes Deus ipse iuvat, God himself helps those who dare. Who knows what we shall accomplish?

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player