September 25th, 1809.

I write this after our customary afternoon performance, as the scenery is being set up for the opening night of La Vestale. The past few days have been a furious succession of quarrels and panics, but I suppose that such things are to be expected in the theatre.

The opera itself could not have been better chosen. There are only seven singers, three of them with important roles. These are Julia the Vestal virgin, sung by Signorina Catelani; Licinius the Roman general, sung by a young man with the stage name of Carlo Panini, but who is actually called Charlie Rolls; and Cinna his friend and confidant, sung by Giacomo Savone, real name Joe Soap – how much better things sound in Italian!

We have managed to reduce the orchestra to two violins, a violoncello, a bass, a flute – played by the able Jem – a serpent, a horn and a motley collection of drums and miscellaneous makers of noise presided over by my dear son Bruin, since these are not needed in the ballets that start and end the opera, where all the bears except my old self are on the stage dancing like maenads.

However, Signora Catelani has been, as Fred succinctly put it, a pain in – well, a region that I cannot decorously mention. She insists on her dressing room being larger than those that the other singers have to share: five men are crammed into one room, though they do not complain; and the only other female singer, who plays the role of the Principal Vestal, prepares herself in a little cupboard under the stairs. La Catelani also demands that her room should be filled with roses, replaced daily, and that there should be plates of her favourite liquorice comfits for her voice (which we have had to buy from a ruinously expensive establishment in Bond Street), and Mr Bellamy’s veal pies to sustain her already ample girth. Nevertheless, she sings admirably, and we must accede to her demands to keep her twittering. In the words of the ancient proverb, Γυνὴ τὸ συνολὸν ἐστὶ δαπανηρὸν φύσει, Woman is generally extravagant by nature.

She is also involved in a liaison with the horn player, a tall and muscular red-haired Irishman called Sean Murphy, who styles himself Giovanni Patata. We affect not to notice. She has had a violent quarrel with the Principal Vestal, Annabella Panettone – real name Ann Cakebread – and we have had to restrain them from pulling each other’s hair out.

La Catelani also objected to having to sing in English, claiming that Italian is the true language of opera. Be that as it may, this work was composed with a French libretto, and I think I have done it a service in rescuing it from that nasal language. I also pointed out that the action is set in the third century BC, a full thousand years before there was a glimmering of the Italian tongue. But it was my assertion that, if her words could be understood by the audience, she would be all the more applauded, that won her over.

The scenery of the second act – the first act is entirely given over to our ballet – is the temple of Vesta in Rome. The score describes it as temple de Vesta, de forme circulaire, but a circular temple is difficult and expensive to reproduce on stage, and we have settled for the customary painted flats. Needless to say, this raised objections from La Catelani, who stridently demanded un tempio rotondo autentico. I was able to quash this demand by pointing out that the round ‘Temple of Vesta’ that survives in Rome is actually the temple of Fortuna Virilis, and that she would surely not want to be accused of participating in a vulgar error. She gave in; I think it was the word ‘vulgar’ that won this skirmish.

She also insists that her principal aria should be performed a third higher than written, to show off her top notes. I am not enamoured of the screeches she emits at that pitch, but we acceded to her demand. Jem and I had to rewrite all the parts for that number in the new key, a laborious task. The aria is sung as she is about to be walled up in a large black pyramid made of canvas: Adieu, adieu, mes tendres soeurs, adieu, which I have translated as ‘Farewell, farewell, my sisters dear, farewell’, and I must admit that it is highly affecting.

We have taken great pains with the climactic scene where divine lightning strikes the altar and relights the sacred flame. The sound effects are not difficult: Bruin has a thunder sheet – a large sheet of iron which makes a loud boom when shaken – and a big wooden slapstick to mimic the crack of the lightning bolt. But how to make the flash? We consulted that eminent natural philosopher Mr Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution, and he was generous enough to give us a portion of an element newly discovered by himself only two years previously. It is called magnesium and, if a pinch of the powder be set on a dish and a flame touched to it, it will go up in a blinding white flare and scare the audience out of their wits.

Anyway, all this is behind us. The performers are rehearsed, the band is tuning up, and I must be off to supervise the bears’ opening ballet. As they say apotropaically in this business, ‘Break a leg.’

September 26th, 1809.

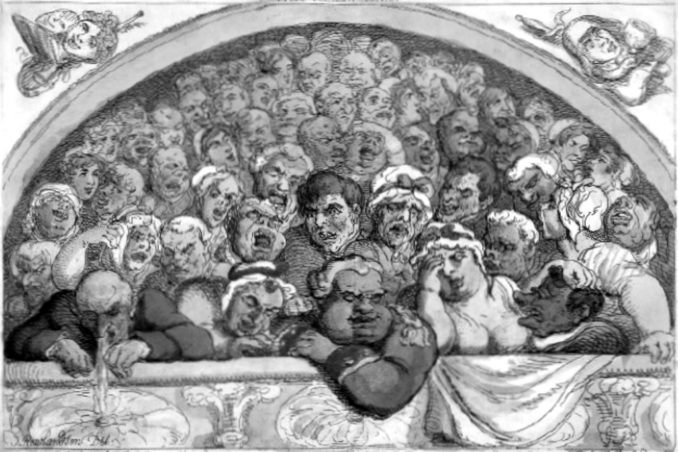

The first night was a triumph – I can use no other word. For all her foibles, Adelia Catelani is as fine a singer as ever trod the boards in Covent Garden, or Venice or Milan for that matter. The audience wept when she was about to be immured in the pyramid, gasped at our artificial lightning, and cheered uproariously at the final wedding duet, Sur cet autel sacré viens recevoir ma foi, which I translated as ‘Upon this altar stone I pledge my troth to thee.’ Even the mob in the galleries were in ecstasies, and we had to wait for several minutes before the bears’ final ballet in order to clear flowers from the stage. The bears danced with unsurpassed elegance, and when we took our final bows they got almost as long an ovation as La Catelani – though I am grateful that we did not get more, or no doubt she would have thrown another of her tantrums.

Afterwards we all celebrated in the empty seats. Fred had provided two dozen bottles of something that passed for burgundy, and a keg of beer that did not pretend to be anything else, and we were all transported by joy and liquor in equal quantities.

La Catelani and Mr Murphy forgot their pretence and embraced each other. I noticed that her Italian accent was slipping, and increasingly often a London diphthong marred the pure vowels of Tuscany. So did Fred, and after a while he asked her, ‘Signora, ’ave yer spent long in London?’

‘Lor bless yer,’ she replied. ‘I ’as to keep up that Eyetalian malarkey for the sake o’ me reputation. But I’m jest plain Ellie Dobbs from Bow to me friends. And you all bin good friends to me.’

Fred poured her another glass and said, ‘Signora Catelani, we is honoured by yer confidence. But we didn’t ’ear that last bit, did we, boys ’n’ gals?’

We all cheered and roared in assent, and Fred added, ‘An’ we’ll keep up the roses an’ lickerish an’ them pies from Mr Bellamy, though I did ’ear as ’ow as it was them pies what done for young Billy Pitt these three years past.’ He was alluding to what were alleged to have been the Prime Minister’s last words, ‘I think I could eat one of Mr Bellamy’s veal pies.’ But the poor man never took a mouthful, and expired shortly afterwards.

2nd October, 1809.

Fred reports that we have repaid our investment, and his account at Cox and Kings is again ‘back in the black’ to the tune of a couple of hundred pounds. But five days of uninterrupted triumph makes one nervous of attracting the envy of the gods. As Pindar put it, Εἰ δὲ θεὸν ἀνὴρ τις ἔλπεταὶ τι λαθέμεν ἔρδων, ἁμαρτάνει, If any man hopes that in doing anything he will escape the notice of a god, he is in error.

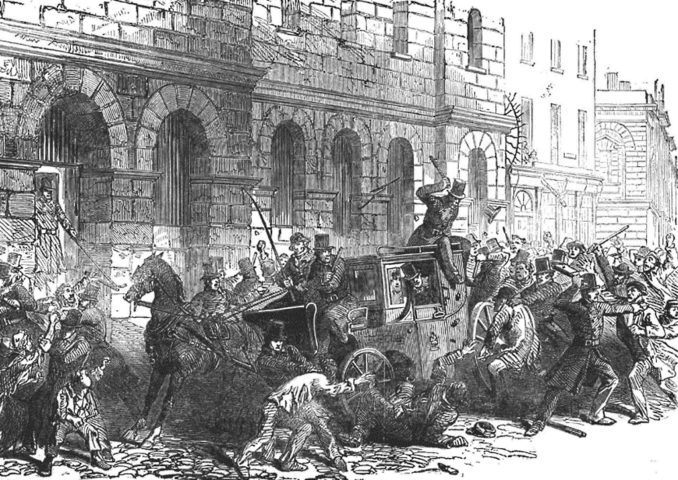

And so it was. Our success in drawing crowds away from Covent Garden has made the house’s beleaguered manager, John Kemble, sadly envious. The Old Price riots still continue, and Kemble has engaged a prizefighter, Daniel Mendoza, to keep order by breaking heads. At our evening performance, as our fashionable patrons were alighting from their carriages, we saw an ugly mob bearing cudgels heading up Oxford Street towards us, and none of them uglier than Mendoza at their head armed with a great club three feet in length.

They set upon our would-be audience, and in a moment a scene of genteel diversion became one of bloody conflict. We bears sallied forth, roaring thunderously, and beat Mendoza’s men back until they fled, but the damage was done. Several blameless members of the public, who had turned out to enjoy an innocent spectacle, were now lying in the muddy road nursing various injuries.

We took them into a downstairs room and did what we could for them, plying them with brandy and reassurance. One of them, a Mr Silas Armitage, who had travelled all the way from Edgware to see the opera, had been knocked cold by Mendoza’s club and had a sad swelling on his bald head. But he rallied, and all of them attended the performance, and we saw him later leaving in his carriage. We heaved a general sigh of relief, thinking that matters could have been worse.

4th October, 1809.

Indeed worse was to come. There has been no further trouble with Mendoza and his mob, and our performances have continued uninterrupted to universal acclaim. But today, after we had finished the usual afternoon spectacle, a pair of Bow Street Runners presented themselves at the box office, asking for Fred – ominously by his full name, Frederick Rowland, which no one uses.

When Fred appeared he was arrested on the spot, charged with the murder of Mr Armitage, and he was dragged away to the courthouse in Vine Street, where he now languishes.

From what we can discover, Mr Armitage left the performance and returned home in apparently good health, but later that night he complained of an increasing headache. Since he had indeed been struck on the head, no one was greatly concerned – but in the morning he was dead. Blood from his injury had been seeping into his brain all the time, and after a few hours it undid this unfortunate gentleman.

The accusation of murder had been made by John Kemble, who was not present at the affray, but he has a dozen so-called witnesses to the effect that that it was Fred who struck the fatal blow – all of them, of course, members of Mendoza’s mob, lying through the gaps in their rotten teeth.

Well, Fred will have his day in court, and we will be there to demolish their story and testify to the truth. On the recommendation of Jem, no stranger to legal proceedings, we have engaged the services of a solicitor, Mr Jeremiah Bundle, who is sure that we have a good case and will secure Fred’s acquittal. But, as Charlie Rolls – I beg his pardon, Signor Panini – remarked to me, ‘’E would say that, wouldn’t ’e?’

Despite our uneasiness, performances continue: as the old adage has it, the show must go on. But we are all consumed with anxiety at the absence of dear Fred, our guiding light and inspiration in this uncertain venture. Our make-believe Italians have kept in character by visiting St Etheldreda’s Catholic church in Ely Place, where they have lit candles to all saints they could find and prayed with honest fervour for Fred’s deliverance. I went with them and, as my candle flickered, I said a silent prayer to St Daniel, the patron saint of prisoners.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player