Sally Bowson couldn’t settle that afternoon. Over a late lunch she had pressed both Martha and her husband about the priest-monk’s fables. They had smiled patiently, confirming them, insisting that those in Holy Orders would not lie, perhaps not tell everything, but certainly not break one of the Ten Commandments themselves, least of all Brother Peran. They seemed quite fond of him, if amused by some of his eccentricities, but were unwilling to elaborate further, pleading they could add little to his scholarship. She doubted that, but it was unfair to press too hard.

Iltud had then gone back to work on his small-holding, but it was increasingly clear that Martha had been relieved of whatever nursing duties she had to keep an eye, no, that was too suspicious, unfair on such kind people, to look after the new immigrants. Her son just loved it here she could see, so easily absorbed by new friends, puppies, farm animals, roads, streams and fields. He could wander freely and safely about with the other children he was getting to know, coming back scratched, wet, muddy and beaming with excitement about his latest little discoveries. All so different from London.

It took her back to her own childhood two and a half decades ago, one with an unusual freedom even then, now almost completely obsolete in the modern world outside. Outside, she caught herself, almost starting to think like a native. I want my life back, not as before, but to see my family, my parents, my husband again. How was he? Was he missing her? Was he bereft at their loss to him, or just their son’s? She knew he had been even more closed, more preoccupied than normal recently; perhaps something big had been building? She hadn’t stopped to think, consumed in her own unhappiness; she had missed the signs, not asked to share his cares. Her spirits, lifted by the absolution that Brother Peran had seemed to confer, sank again. Blinded by his loquacity, she had not done this morning what she had set out to do. She would return to the little church, get down on her knees and ask for guidance, for answers, to be able to forgive herself.

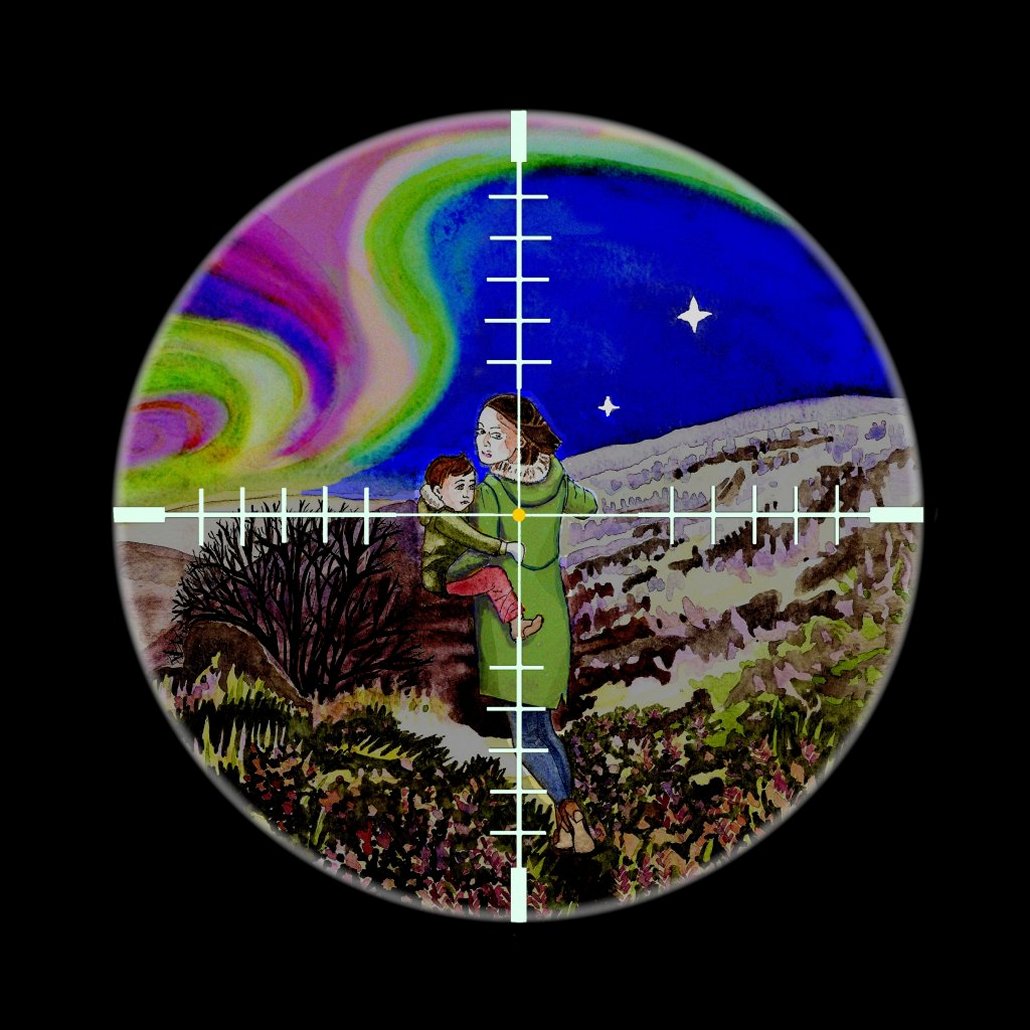

Firstly though, she had to help Martha at home, to repay a little, start to feel useful. The afternoon wore on, filled by the endless little household chores of all homes. She began to see the drawbacks of a life without electricity: no vacuum cleaners, no washing machines and no hot water at the flick of a switch. If she had harboured any illusions about this being an antiquated Disneyland, an earthly paradise of peace and contentment, those few hours started to shred them. And then she thought of the men’s weapons, cold killing implements – she had never liked Andy keeping his handgun in the house – needed to maintain this place against something Mark had said was trying to press in. Everyone here seemed to feel safe enough, but it wasn’t Eden that was certain. She would ask the priest about them, what they were called, the Guardians, when she returned to the church later, perhaps before dinner. She had meant to this morning, but like so many of the questions she wanted answered, they had been lost in the flood of his poetry. Perhaps, he was even brighter than he looked? She would not be so easily distracted the next time.

She went with Martha down to the little general store by the warehouse, accompanied by her son and Martha’s grandson, both of whom she had promised to treat if they were good. She felt that, as a guest eating and sleeping at their expense, she should contribute to the cost of the household, buy some things for her hosts. Martha had smiled and shaken her head, explaining that not only was there no electronic money here, invisible money she called it, that even her paper notes and coins would not be accepted. Indeed, with no calculators or computers, they had never decimalised, had never seen the need to use tens rather than dozens; a reluctance reinforced by their remembrance that decimalisation was the invention of the French Emperor Napoleon, the author of the first cataclysm as they called it. So, they were still using pounds, shillings and pence.

Martha had shown her some of the coins; let her examine them in her hands. Some were old, a hundred or more years, worn by repeated handling. Many of these were from outside, from Britain, she realised with a shock; there was even a golden guinea from the reign of George IV. Martha was proud of that, it seemed more an heirloom to her than a sum to be spent. Other coins looked locally produced, but modelled to resemble the ones from outside, although not-so-fine as if made with less sophisticated machinery.

With a start, she realised there was no paper money, the higher value amounts were all denominated in gold and silver, the smaller in bronze. Farthings, ha’pennies, pennies, three penny bits, silver sixpences and shillings, half crowns and crowns, ten-shilling coins and pound coins, and that one golden guinea. Martha explained how they still used sovereigns for the largest value transactions, largely for the business of the authorities. She looked at the silver coins again, most were local, portraying Britannia with the spear and shield. The classics student in her recalled Britannia was, in origin, the Greek goddess Athena on the on of Alexander’s Successor Lysimachos. On the obverse the head of a late middle-aged man, the Duke, Martha explained, and a small Celtic cross with no lettering. The designs of the local coins seemed to vary little between types or level of wear or age. Simpler in some ways, more complex in others, she realised.

They walked past the warehouse on the way to the little station halt and store. A train was pulled up; steam hissing quietly from funnel as if at rest but not sleeping. Other than a small coal wagon, there seemed to be a passenger coach, one open goods wagon and two enclosed, whose side doors were open. Her son broke free of her hand in his frenzy and sped towards it onto the open platform. She raced after, scooping him up in her arms just as he about to try to climb in one of the good wagons’ open doors. A man came to the doorway carrying a large cardboard box, he must be in his sixties she thought, but he handled it as if containing little weight. He grinned at her; he had been a little boy once.

She carried the squirming Josey back towards Martha at the edge of the platform. As she retreated two younger men came out of the warehouse’s open double doors, one empty handed, the other pulling a small hand-cart. They smiled at her, they were clearly relieving the train of its cargo. Her eyes glided past them into the semi-darkness of the open warehouse behind; it was almost full, mainly cardboard boxes similar to the one the older man on the train was passing down to his empty-handed colleague on the platform. Besides them she could see some heavy looking wooden packing cases stacked low on one another, and various other boxes and metal drums of different sizes that were harder to make out in the shadows.

The older man had got down and approached them, embracing Martha as he did so. He smiled again at Sally.

“This is my brother, Docco, who works as the guard on this service.”

He rolled his eyes. “Sometimes I wish there were not such a fashion for naming us after our native saints. Welcome, isn’t she grand?” He pointed to the little engine and, looking at the wriggling Josey who was still fighting to break free, smiled “Would the young boys like to come up into the cab and see her in all her glory?”

“Good idea Docco, for once”. Martha was laughing now. “You can avoid the hard work and play trains with your two little friends, while we go to the shop in peace.”

Sally’s son gave her the most beseeching look she could remember and, promising to be good, toddled off squealing with his two new friends. “Come on,” said Martha, “let’s use the peace to get what we need.”

She tried hard not to be disappointed by the village shop. She had imagined it to be like an Aladdin’s cave, one of those old shops you saw in children’s films, stuffed full of oak and glass cabinets running floor to ceiling and wooden counters, all piled high with jars, packets and boxes of all descriptions containing many coloured wonders from around the world. Passing hessian sacks of coal and other similar goods on the way in, she saw it was tiny, containing mainly basic commodities in sacks, jars and boxes holding items such as flour, salt, a little sugar, potatoes, dried pulses, preserved meats and fish, a few bottles of cider, beer and lemonade, boots, tools, soaps, belts etc. She looked beyond the little shopkeeper who was busy serving Martha. There on a couple of back-shelves were more highly coloured items, goods brought in from the outside as she was increasingly thinking it, clearly expensive relative to those produced locally. Her spirits rose a little with the familiarity contained there, some tooth-paste (what about dentists, do they have them here, she shuddered), brushes, cleaning materials, razor blades, cartridges for guns, tinned foods, rice, some spice jars it seemed, matches, a few other items, but Aladdin’s cave it wasn’t.

She followed Martha out and round the back onto the platform where the train was now building steam and Martha’s brother was holding his two charges by the hand. He was smiling as broadly as they were, “I’m sorry, but I couldn’t keep them off the coal bunker.”

They were filthy with soot and coal dust, but clearly heedless. Before she could admonish her son, Martha lent forward and gave them both a decorated ginger bread man she had bought in the store, scolding her brother, “Honestly Docco, I swear you are more a child than either of them.”

They waited, watching the train puff out of the station the way it had come in and disappear into the distance down the line before they commenced the walk back to the house with the children. The warehouse was now locked up again and the men had seemingly vanished. She tried to probe Martha on what they kept inside, but her hostess became cagey once more, trying to change the subject. This time she would not relent, repeating her enquiries. Sally was starting to worry now.

As they entered the front gate, ushering the children through, Martha conceded defeat. “I shouldn’t discuss that, you try with Iltud tonight. All I will say is we can’t pay for the things we need to bring in from Logres just by exporting our preserved meats and fish, and lobsters and crabs.”

Sally gave up. She would clearly get no further until this evening. She helped put everything away, cleaned up the boys and then, excusing herself, headed back up to the church. Brother Peran wasn’t there, or at least didn’t answer her knocks on the locked vestry door, so she went up to the altar, knelt down and tried to pray, to confess her failings and her fears, but she seemed to get nowhere. Her mind was full of unanswered questions; this place wasn’t clearly all that it seemed. She felt as if she were in some mystery series on TV, a character trying to survive the twists and turns of the plot, near helpless in the hands of others no matter how kind they seemed. She needed answers to be able to think straight, to make decisions on behalf of her and her son. If only Andy were here, they could decide together, take strength from one another. Should we try to escape and, if so, how? Were they lying to her about the need to be ‘touched’, whatever that was? She shuddered at the thought of trying to go back the way she came; she felt trapped by the uncertainty, only answers could allow her to work it out.

She left the church and headed down the path through the little churchyard; as she closed the gate she glimpsed something towards the back wall of low dry-stone; a grave stone, not a Celtic cross like the others, more like an eastern cross, Greek or Russian? Odd. She had to get back to what she was starting to think of as home in her weaker moments: Iltud would have to help tonight or she would lose her mind.

© 1642again 2018