There was a call on one of his secure pay-as-you-go phones. “Abdul, it’s Suleiman here. Amallifely’s been martyred, shot outside his house this morning. The police are all over it and have been searching the house and asking lots of questions of everyone.”

“Then why are you calling me on this number, it may have been compromised? Meet me in forty minutes at point B.”

The younger man was panicking he realised, his inexperience showing through. Better contact his leader, Badr, to confer. They might have to accelerate or abort their mission, but it wasn’t his decision. One more call with this phone then dump it. No answer. Thirty, sixty, ninety minutes later, still no answer. Concerns began to rise. Alternative numbers not answering either. Better go around – a risk he knew – give it twenty-four hours then. Low key for the rest of the day other than meet Abdul and the others; they can ask questions of local sympathisers to try to fill in the gaps.

He turned on the local news. There had been a drugs related murder according to police, in Amallifely’s street. He was really worried now; it was too much of a coincidence. Something had gone seriously wrong and his leader had disappeared. Yes, too much of a coincidence, Badr had all the contacts outside their cell; if he were taken they could all be rolled up. Amallifely, Badr’s deputy, would have known what to do. They were taught to be flexible, self-sufficient and unpredictable. They might not have very long so they had to move fast. Allah would steer them and provide. Devotion, dedication could overcome all, even in this hostile infidel land. As next in authority now, unless Badr re-emerged, it was his call. Strike now before it was too late, even if not fully prepared? The panic, the fear began to recede as he came to his decision. It would be tomorrow evening at the softer alternate target then; now to tell the rest of the team.

Sally Bowson turned the key in the ignition again, and again, nothing, dead, no electrics at all. The last vestiges of daylight were fading into the west over Cornwall, blending with the early moonlight to barely illuminate the moorland stretching away all around her. The car would pack up here, on one of the loneliest roads on Exmoor, a road she had taken hundreds of times to her parents’ cottage just beyond the western fringe of the moor. The clear early spring night was already bitterly cold and clear, and the heater had gone with the electrics. “Are we at Grandma’s yet?”

“Nearly sweetie”.

“Why have we stopped”?

“Just resting the car.”

She picked up her phone. Her Dad could come and get them: it could only be nine or ten miles. Please Lord, let there be some signal. The phone seemed to be off. It wouldn’t turn on. Had the battery died? She had no spare with her. No, Lord, no, not now. She wasn’t normally one to panic, but she had Josey in the car and it looked like a freezing night. The stars were coming out now, the sky was clear and yes, the temperature was going to crash. That settled it. There were farms, even up here less than every mile or so: it could be hours before a passing vehicle came by. She leaned back in the car and released her son from the seat straps. “Put your coat and jumper on sweetie, we’ve got to go for a little walk.”

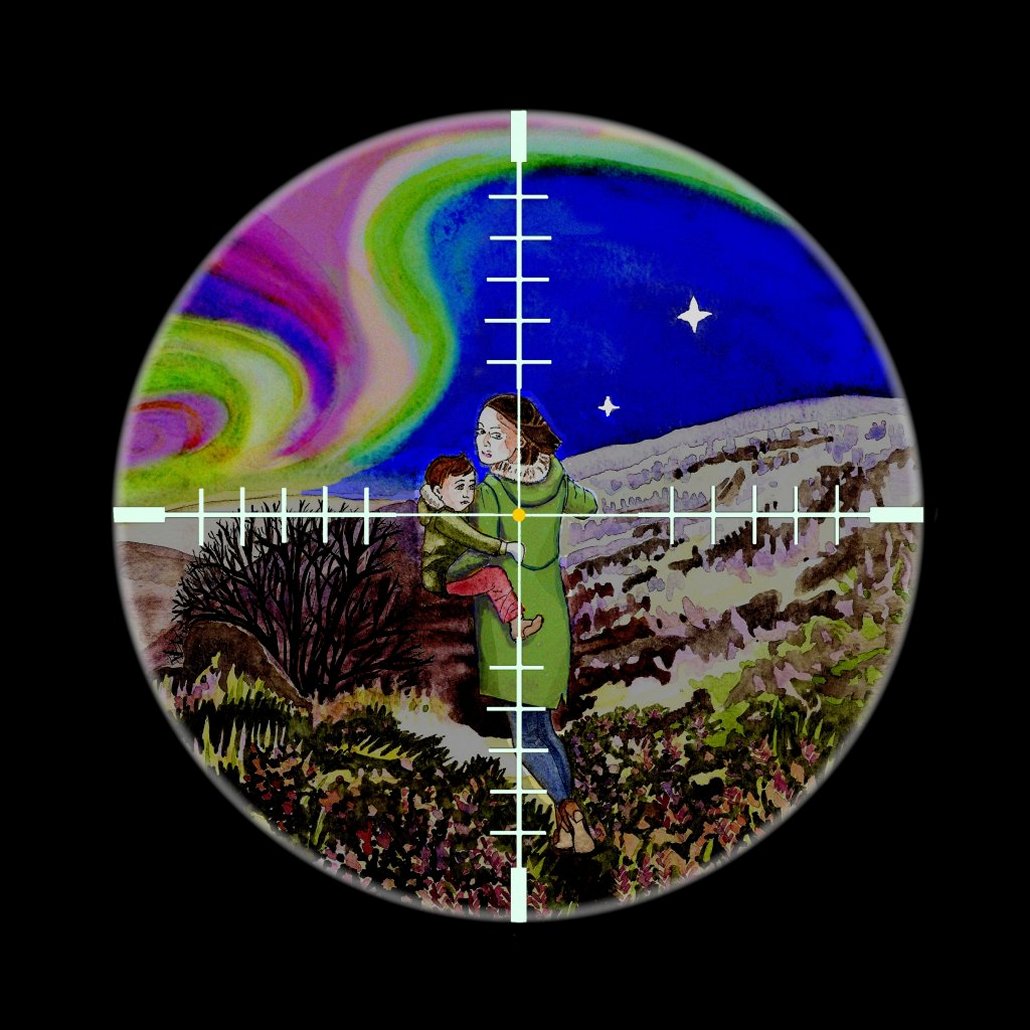

She reached over and pulled out the torch she normally kept in the glove compartment. No light, damn, the batteries must have run out. She got out, let out Josey and they headed west along the road. She touched his head. Ouch, the crackle of static made her jump, the air seemed to be crawling with a pent up electric charge, weird. She went on a few further paces and looked up. The Northern Lights! It was a long time since she had seen them this far south, let alone such a magnificent display – greens, blues, purples – almost as if they were all around her now. The charge in the atmosphere was getting worse. Something wasn’t right. Better not hang about. She swept a faintly protesting son into her arms and set off, jog-walking, eyes down, looking for that first farm gateway. Words from her college years broke into her distracted mind, ‘In the middle of the journey of our life, I found myself in a dark wood, for the straight path was lost.’ Dante’s Inferno wasn’t it?

She was fearing a physical loss of direction now, not just an emotional one. A mist seemed to be rising, diminishing the brightness of the lights in the sky; visibility was very faint, but there it was, a gateway, or at least an earth track with an open rusted metal gate slumped to one side. Second thoughts rose, but a sixth sense or mother’s intuition impelled her not to retreat. She hurried down the falling rutted track, the heather closing in on both sides so that finally only the wheel tracks remained. There was no sign of light or habitation. On the point of abandoning this track as a false start and heading back, she heard, or thought she heard, something like animal footsteps rustling the heather away to the right. “Hello, hello?”

No answer, Exmoor ponies, or sheep? The rustling footsteps picked up speed seemingly coming towards her and there seemed to be more now, both to the right and behind. She felt fear, the real primal kind; this was no longer the moorland she knew so well and had loved so much, but an unfamiliar hinterland of unseen menace. She stumbled down the track, the heather snapping at her jean wrapped legs and ankle boots, her dark brown, almost black, neck length hair sweeping across her eyes as she clutched an alarmed Josey to her breast, his dark brown eyes staring up at her, her mood silencing the normally interminable stream of questions and observations.

Whatever they were, they seemed closer now in the strangely coloured darkness, on all sides but not in front. She was running now, praying not to lose her footing. Out of the night came a guttural whispering, a subdued cacophony of communication between unseen terrors.

“Dear God,” she heard herself gasp as she glimpsed a dim yellow-orange luminescence ahead, almost similar to the patina of light given out by the oil lamps her parents used to keep for the frequent power cuts of her childhood. There was another, and another… and then, a faint metallic squeak, and another, again from ahead.

The sounds behind were very close, almost imminent, possessing a feral intensity. She was exhausted from stumbling along with a mute Josey in her arms, bathed in a cold sweat, her heart pounding, pushing up towards her throat. The mist and twisting, writhing sky lights were all around as she finally lost her footing on the broken track and fell headlong into the heather with a cry of despair, cut short as her head slammed into a protruding lump of granite. For a split second, part of her retained just enough consciousness to later recollect a shape running up to her, a swinging light in one hand and something dark in the other, with other lights swaying up behind…

In silence, the Abbot left the chancel along with the Brothers, a silence they would all observe until the following day, with the single exception of himself. He turned and followed the cobbled path up to the stone built fort of ancient design which doubled as the Duke’s small palace. The Chamberlain met him at the main door as he did every night at this same time, something that they had been doing for many years now after a string of others before them. It was held to be a vital tenet of Duchy tradition, the importance of which the old man himself had stressed to him after his election. So, here he was again, following the Chamberlain slowly up the candle lit stone steps, pausing at the ornate oak door along the landing and following him through into the chamber.

A wood-burner was chugging away in a corner of the room, holding the evening chill at bay for the sleeping occupant in the silk covered bed. He always marvelled at those silks, a gift from the east of exquisite construction, the byzantine designs and colouring reminding him of the icons held within the Abbey. There he lay sleeping on the bed as he always was when they came to bless his recumbent form and to pray for God’s protection of the ageing man beneath the covers. White haired, he looked like as a man in his sixties might look after a life of hard service. His face was always expressionless, as if he never dreamed or as if his soul were somewhere completely “other”.

He gave the blessing and made the short plea for divine protection as normal, and then it was over for another twenty-four hours. He had never lingered in this room, had never seen it in the natural light. For him the silk window hangings were always drawn across the barred glass, the hanging oil lamps lit, keeping the darkness at bay, the wall tapestries and floor rugs of uncertain detail in the dim light. He followed the Chamberlain out; looking back into the room and on to the form of the figure about whom so much was said.

The waiting night servant locked the door behind them and sat on the chair beside the door as he always did. The guard on the top of the stairs nodded wordlessly to them as they descended. Another would be up there as well in the room opposite all night. No one would take any chances, not even somewhere as safe and secure as here. The Chamberlain thanked him, as he always did, and went back to his own quarters in the fort. The night porter locked the main door behind him as he blessed the man as he always requested, and headed back to his cell. His mind, reassured by the continuity of the ritual, the timelessness it seemed to possess, began to think of the dawn and the coming of Easter and of those in harm’s way on the outside.

It was almost eleven as Andy Bowson made it to his hotel room for the night, just as his personal mobile phone rang: it was Sally’s mother, “Andy? Justine, it’s Sally, we were expecting her here hours ago with Josey, but she’s not arrived, her mobile’s going straight to answer phone and she isn’t at home as far as we can tell. She phoned this morning to say she was coming down today and never turned up. Her supper’s ruined. Have you heard from her?”

“Don’t worry Justine, I’m sure she’s fine” he found himself replying almost automatically. “If we don’t hear from her by morning I’ll get my colleagues on to it.”

He knew things hadn’t been right between them, but she had never taken off to her parents before without discussing it with him first. And she hadn’t contacted him for over thirty-six hours now; better not wait until the morning. He picked up the phone again to speak to the local duty officer at Devon & Cornwall Constabulary. After all, they were all members of the police family.

© 1642again 2017