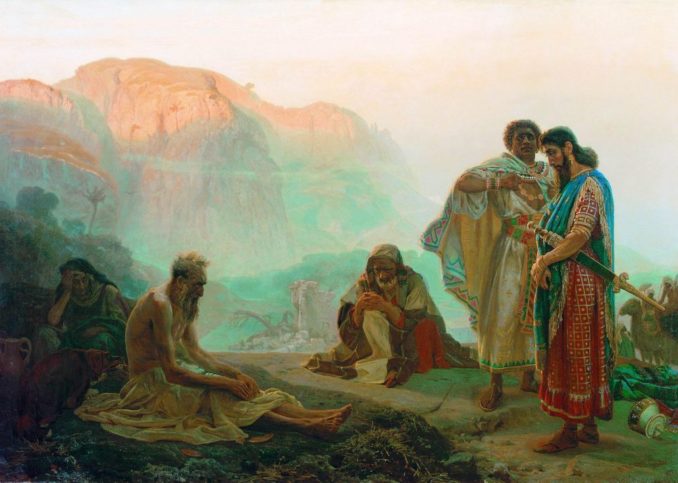

Ilya Repin [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Those of you with good memories may recall that I touched on this issue in a couple of my earlier Speculative Theology articles, specifically addressing a reconciliation of the ideas of Free Will and Predestination, because as ever the Problem of Pain is another iteration of the gift of Free Will. The book of Job is focused almost heavily on this issue and how one should respond to apparently undeserved tragedy. It provides no easy or trite answers but is a meditation on the virtues of stoicism and the limits of human wisdom. Most people have no problem with the wicked getting their just desserts – it seems to fit the idea of a moral order in the universe – but the good dying young or the innocent suffering challenges the whole notion of a loving divinity.

Job is another of those previously much studied Old Testament characters who has slipped down the modern theology popularity rankings because it’s tough and seemingly cruel. Even a century ago, it was much more in vogue and was almost certainly influential in Shakespeare’s portrayal of King Lear. Our sheltered lives make dealing with the issues presented by Job unpalatable, but to earlier generations who were used to scarcity, danger, injustice, infant mortality and most illnesses being incurable, Job was a significant figure worth study because tragedy was almost an everyday occurrence.

Tough times make people tough or go under. Job is not a read for snowflakes, but for Puritans used to challenge, doubt and struggle.

Job the Book Itself and its Attribution

As with any part of the Old Testament, the date of the composition of the Book of Job is hotly debated, but most scholars put it in the time of the Babylonian captivity (first half of 6th century BC) when many of the earlier books reached their final form. Some scholars believe that this was when they were composed, but for others, myself included, this was when final versions were agreed as set texts after editing, but drew on earlier versions.

That said, I tend towards the view that Job itself actually was composed during the early 6th century simply because Job was almost certainly not an Israelite but from a related Semitic kingdom, probably Edom south-east of the Dead Sea. The Hebrew book of Job doesn’t say much about him other than that he was a rich and fortunate man from the ‘Land of Uz’ (most commonly identified with Edom), but the Greek version adds a final extra verse, probably taken from earlier Hebrew non Biblical writings, that says he was the grandson of Esau, the grandson of Abraham who married into the royal line of Edom and whose children did not go into Egypt with their cousins, the sons of Jacob.

This means that by the time of the Exodus several centuries later, all Hebrew knowledge of Job would have been lost and only reacquired when Moses married the daughter of Jethro, high priest of the Midianite tribal federation located south of Edom. It was almost certainly Jethro who reintroduced the worship of Jehovah to the Moses, and that it seems that Jehovah worship had continued to some degree among the small kingdoms of the area related to the Hebrews during their absence in Egypt. But how much memory of Job survived is moot, and it may have been little more than a folk tale that was written up centuries later by a once more afflicted Jewish people asking themselves how to endure slavery in Babylon and why God had permitted it to happen to them.

So that’s why I tend to the explanation that Job is a musing on the problem of pain from the 6th century BC projected onto a dimly remembered figure from many centuries earlier.

A Potted Summary of the Book of Job

It’s an interesting book in itself, being a mix of prose and poetic passages, with the latter appearing in a number of ‘scenes’ in the form of monologues and dialogues, and takes some interesting twists and turns.

Job is initially portrayed as very wealthy and blessed with children, consistent with the ruler he was elsewhere said to be.

Satan (meaning the ‘accuser’) challenges God by saying that the famously pious Job is only righteous because God has blessed him with such good fortune and that Job would curse God if it were removed. Accepting the challenge, God allows Satan to send disasters that kill Job’s children and destroy his wealth, but not to kill Job himself. Job still does not denounce God, so Satan then afflicts Job with painful boils, and now Job’s wife urges him to curse God, but Job refuses and argues that God’s gift of life brings both good and evil.

Now Job is being worn down by his continuing suffering and wishes to die to escape his misery. His three friends try to console him, saying that because God is just, Job must have done something terrible to bring such ills on himself. Job denies it, his power of resistance is failing, and he says that God is treating him unjustly as he is an innocent man.

There is now another dialogue involving another man which discusses the limits of human wisdom, and that Job might be innocent of Sin, but God must have just reasons for allowing Job to suffer that are beyond human comprehension. This is the argument of enduring faith being greater than human wisdom. Job is in despair because he can’t understand why.

God now appears twice to speak to Job in the form of a whirlwind, but does not answer Job’s demand for an explanation, but merely that He, God, has far greater issues, including the order of the cosmos, than just one man’s tragedy and that Job simply can’t understand what is at play or the nature of divine wisdom.

Job finally accepts that the explanation is beyond his limited wisdom and repents of his self-pity. God then tells Job’s friends that their attempts at explanation are wrong and that the correct response is Job’s acceptance of his limits and persistence in his faith in the just nature of divine providence.

God then restores Job’s losses and gives him even greater fortune than before. Job has failed in his quest for an answer comprehensible to his human condition (so has Satan because Job didn’t curse God, but rather himself) but his faith has not failed and that is the thing that restores him.

Meanings and Lessons

So when epitomised like that, one can see why it is regarded as a meditation on some of the great enigmas of life presented in the form of an allegory projected back onto an earlier legendary figure of famous piety, and that it deals with the big questions like the gifts of life and free will and their Implications, the problem of pain, the problem of human religion, the limits of human wisdom, and the nature of true faith and the response to tragedy.

So how do we make sense of all this? As ever when looking at these ancient stories there are deeper layers of meanings within the narrative. For me, there are at least five here.

- The Challenge to Mechanistic or Magical Religion

Ancient polytheism had more similarities with magic than with monotheistic religion in many ways, not least the belief that if one followed a particular ritual or made a sacrifice, one could derive material benefits from the gods or spirits, hence the growth of gods and goddesses with specific skills or areas of responsibility to whom one would address one’s needs.

Until the advent of monotheist thinking among the Greek philosophers for instance, this was rarely challenged outside Jehovah worshippers or followers of Zoroaster. The first challenge was Jehovah’s stricture to Abraham banning human sacrifice (disturbingly common among most Bronze Age polytheists), probably circa 1900 BC.

In the story of Job, his friends still think in mechanical or magical terms – Job’s blessings are because he is faithful and his tribulations because he has offended God. Satan’s challenge to God is that this is the real nature of Job’s faith, it’s magical rather than spiritual. The whole story turns on this question and Job eventually, after much soul searching, passes the test and for the Jewish reader in the 6th century BC, clarifies the exceptional nature of the Hebrew faith from the polytheistic world of the Babylon in which they are exiled.

- The Limits of Human Understanding

“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? Declare, if thou hast understanding.

Who hast laid the measures thereof, if thou knowest? Or who hath stretched the line upon it?

Whereupon are the foundations thereof fastened? Or who laid the corner stone thereof;

When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”

In the dialogue between God and a questioning Job, God reminds Job that he created the universe and gave life to Mankind, and that it’s beyond the wit of the latter to fully understand His purposes or the way things work. In other words, Humanity’s ability to comprehend is limited by its physical constraints, and that it must just have faith in the questions beyond its understanding.

This is the hardest thing for modern humanity, armed with the latest scientific theories and limitless ambition to keep learning, to accept and is perhaps partly at least for the decline of religious faith in much of the western world. And yet I remember seeing the famous cosmologist Sir Martin Rees, Astronomer Royal, interviewed in which he said that he no longer believed that humanity could discover the ultimate questions about the nation of Reality, not because we couldn’t ask the questions but because our limited monkey derived brains could not understand the answers, something which also reminded me of the quantum mechanics theorist who said that anyone who said they understood how quantum mechanics work was a liar or a fool.

Extraordinarily, this is the conclusion of the final dialogue between God and Job, proof that the ancients were no less intellectually sophisticated than we.

- The Gifts of Life and Free Will, and their Implications

Job has moral agency – or freedom to make a choice – even though he has limited knowledge, a very human condition as we all make every decision on that basis of using our prior experience and intuition to make a choice in every situation, so every decision is based on a degree of faith informed by our understanding of the world – that what has happened in the past is likely to happen again if circumstances are identical – a fundamental basis of scientific enquiry after all.

In having Free Will, Job like all humans, has the ability to choose right or wrong, and exists in a universe in which good and evil consequences are permitted. Such consequences may have appalling effects on others seemingly far removed from the decision maker, the ‘Quantum Butterfly Effect’. Complex systems (about which I have written before) can produce seemingly (from a parochial point of view) to have chaotic and even arbitrary effects far removed from individual morality or choices. Now elevate that to a physical universe in which impersonal forces operate, according to universal laws, but their sheer complexity creates the impression of an uncaring and arbitrary universe because it just runs on heedless of us.

Clearly if God stepped in every time an individual was to make a bad decision or be affected by a conjunction of other forces, there would be no Free Will or Cause-and-Effect. Humans would no longer be moral agents and the universe no longer operating on the basis of abstract fundamental principles. So evil consequences and choices have to be permitted to exist within the universe, and to be able for all sentient creatures to embrace. This is what the quoted piece of Jehovah’s dialogue is saying to Job – ‘you are subject to greater laws of the universe which have to be allowed to operate unchecked if you are to have Free Will, no matter how unjust it may seem to your parochial viewpoint’.

Job struggles with this because, like all humans, he is at the centre of his own universe, it all exists to serve him, and by implication so does its creator. But it doesn’t, he’s looking through the wrong end of the telescope – it’s the other way around and he exists to be given the chance to fulfil purposes greater than himself beyond his comprehension.

In a way it’s all summed up by the allegory of the Garden of Eden and the Tree of the Fruit of Knowledge of Good and Evil – by eating the fruit, humanity achieved moral agency and Free Will, with all it’s consequences for joy and suffering.

- The Triumph of Faith over Bewilderment and Despair

One can succumb to the obvious temptation to say that fate is capricious and that either there is no God or only one that is uncaring because He permits His creations to suffer. I’ve lost count of the people I have heard say this. That is the reaction that the Satan is trying to provoke in Job – anger or disbelief – but God has more faith in Mankind than has Satan and, so it turns out, does Job in God. In some ways, Job has parallels with Noah as both are characters who retain their faith when most others around them don’t and mock them for it.

Job accepts, hard though it be, that his comprehension is limited by his humanity and that he must place his trust that it is all for the best, even though it may be crushing at the time. In other words, only Faith can see him through bewilderment and despair. Certainly for myself, I have sometimes faced the most crushing disappointment, rejected for a job I really wanted or a relationship collapsing, and then a year or two later looked back with the benefit of hindsight that it was for the best because a better opportunity came long, so much so that I came to develop the capacity never to panic or lose my nerve in extremely tough situations, not from optimism but from faith it would all work out if I kept doing the right things.

So its Job’s faith that sees him through; without it would not have worked out for the best; he could have succumbed to despair or disbelief, and been left stranded there. Without faith and hope that things may get better in future when undergoing dark times, why would anyone persevere?

- Job and Jesus

Those who have read the previous articles in this series may recall that I have speculated that the personalities and stories of the Old Testament prophets all, in different ways, point to Jesus, His personality and mission, and the this is why Christ is always presented as the fulfilment of the core message of the Old Testament.

This is particularly striking to me when, in the climactic moments of the Gospel story, Jesus accepts his fate while praying in the Garden of Gethsemane, even though he fears what is to come, and later dying on the cross He cries out, “My God. My God. Why have you forsaken me?” Just so human and so like Job, the dark night of the soul, then acceptance of the awful things happening and pushing on by faith in the belief that far better is to come once through the darkness.

So Job’s suffering and response to it points the way to the greater ones of Christ to come, and this is why, until recent times, Job was much more studied in a harder and more precarious world.

So, I hope you will agree with me that there is far more happening in Job that certainly I had previously thought. It’s a profound and sophisticated meditation on the deepest questions about the human condition and our responses to it. One can see why it might have been written when it was, in a long dark night of the soul of the many Jews held captive in Babylon, but it’s more than a means of sustaining the despairing, valuable though that is. It helps us understand what it is to be human, our place in the order of things and our best response to tragedy. I will never look at the story of Job in quite the same way again.

© 1642again 2018

Audio file

Audio Player