“I feel as if I should be angry with that child, that naive young girl. Or that I must not forgive her for not recognising the nature of that monster. For not being aware of what she was getting into and especially that I went along without thinking because I wasn’t fanatical. I could have said, ‘No, I’m not doing it. I don’t want to,’ but I didn’t do that. I was too curious. I also didn’t realise that destiny would take me somewhere I didn’t want to be. But, nevertheless, I find it hard to forgive myself.”

As we reach the end of a long winter that saw snow remaining on the hills until mid-April, we might address the science behind global warming. Not a phoney cause and effect claiming a 0.04% concentration of carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere has an effect upon the weather, but rather the real measurable reason behind the global warming issue – one that lies between the ears.

The perceptive inquirer puts aside meteorology, climatology and physics and is obliged to a more honest prospect. The problem lies not at melting poles or burning equatorial latitudes but in the grey matter within collective minds.

Throughout history we have seen how beliefs and ideas can spread like wildfire, taking hold of entire communities and shaping their behaviour. This phenomenon is called mass psychosis, and it has far-reaching implications for our increasingly interconnected world.

In this article, we will explore the science behind mass psychosis and how it relates to the belief in global warming. We will examine the role of propaganda, the history of environmentalism and the psychology of belief formation. By understanding the root causes of this phenomenon, we can better address the perceived issue of global warming and its impact on our world when combined with the skills of the propagandist.

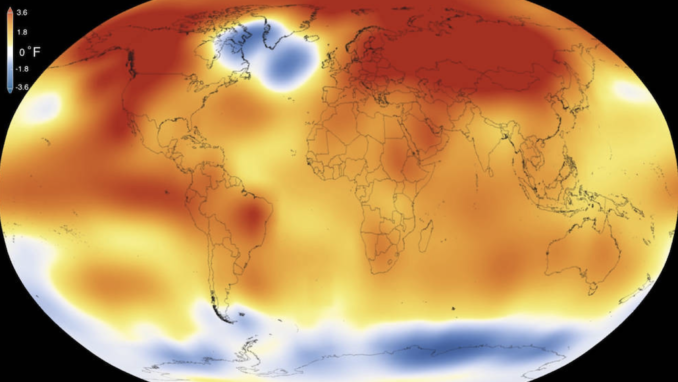

Record-Shattering Global Warm Temperatures,

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Global warming as a mass psychosis

Mass formation psychosis is when a large part of a society focuses its attention on a series of events and that attention is held to one small point or issue. Followers can be hypnotized and led anywhere, regardless of data proving otherwise. In his article The Mass Psychosis Of Our Time, biomedical gerontologist and specialist physician, Marios Kyriazis writes,

“It happens when a large section of society loses touch with reality and ends up in delusions. Those who suffer from mass psychosis do not realize that it is happening. People in this society subconsciously sink into a lower moral and spiritual level, become more irrational, irresponsible, emotional, unstable and unreliable, and worst of all, commit bad deeds they would otherwise never commit. Mass psychosis begins with fear or anxiety, which leads a person to a state of panic. There is a pervasive atmosphere of terror that ‘the enemy is among us’.”

How convenient if that enemy is colourless, odourless, tasteless and invisible, with carbon-phobia, Net Zero and the difficulties they create depicted as if for the good of the planet rather than for the self-interest of corrupt politicians, green-washing corporations and virtue signalling vacuous celebrities. Other bizarre obsessions and their consequences have been recorded through the ages:

- The Salem witch trials in 1692, where more than 200 people were accused of witchcraft resulted in 19 hangings and one person being crushed to death.

- The dancing plague of 1518 in France, where hundreds of people danced themselves to death due to a possible combination of stress, famine, and ergot poisoning.

- The appearance of the leaping demon Spring-heeled Jack in Victorian England, where people reported being attacked by a supernatural being with the ability to leap great distances.

The modern age is not exempt. In 1983, a West Bank fainting epidemic saw 943 Palestinian teenage girls and a small number of IDF soldiers experience fainting spells and other symptoms. The quote that begins this article are the words of Traudl Junge, a personal secretary in the Frurbunker towards the end of the war.

All of those events pre-dated the internet and a rolling news-dominated public media space whose obsessions become ubiquitous. Although the dancing plague may be attributed to the hallucinogenic effects of a chemical produced by fungus-infected grain, the others exhibit more as mental disorders based on hysteria. What of global warming? Might it be a mental disorder rather than a set of climatological circumstances?

Global warming as a mental health issue

Global warming is already recognised as a mental health issue. But which comes first, the donkey or the cart? A mainstream understanding of the psychology of global warming revolves around the mental health impacts of climate change on individuals. According to a poll by Pew Research Center, climate change is perceived as being one of the world’s top threats, ranked alongside terrorism and cyberattacks.

Extreme weather events such as wildfires and hurricanes attributed to climate change can lead to depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and climate anxiety. Natural disasters also have a massive psychological impact, including increases in PTSD, depression, and substance abuse, alongside wider social tensions and an increase in domestic violence.

The emotional responses caused by climate change can be harnessed to promote advocacy and social action. The immediate and personal impact of climate change is more powerful in motivating pro-environmental behaviour than abstract analysis. The psychology of global warming is a growing area of research, and a task force on the interface between psychology and global climate change has been established to address the challenges.

But from which end of the telescope should mental health/global warming be viewed? The counter-argument would be that it is a belief in global warming that is a mental disorder – of the mass psychotic variety. The evidence is there.

Catastrophising the ordinary

One of the key features of mass psychosis is the tendency to catastrophize ordinary events. Small environmental problems are portrayed as global crises. This is often seen in the way that environmental issues are framed in the media. Local-scale problems like droughts or wildfires are presented as global crises, creating a sense of panic and urgency.

after monsoon floods struck Pakistan,

Department of Foreigh Affairs and Trade – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Are these events catastrophes or are they ordinary events that are catastrophised? Last summer we had the worst (and wettest) drought for 400 years during which it kept on raining. As for the much-repeated phrase ‘month’s rainfall in a day,’ it is not uncommon. Entire dry months have always had less rain than a showery afternoon. The monsoon season in Pakistan is now reported not as an annual event but as a catastrophic and unprecedented one-off. Likewise, tornados in the US during the tornado season.

While it is important to address environmental problems, the tendency to exaggerate their impact can lead to irrational decision-making. For example, the commitment to extreme measures such as reducing emissions of carbon dioxide to an impossible and irrelevant Net Zero. These kinds of solutions are not only impractical but harmful.

Stigmatising dissenters

One of the most insidious effects of mass psychosis is the way it stigmatizes dissenters. When a particular belief becomes a cultural norm, those who question it may be ostracized or even punished. This can lead to a culture of conformity where independent thought is discouraged.

In the case of global warming, those who question the mainstream narrative are often labelled as “deniers” or “sceptics.” This creates a culture of fear where people may be hesitant to express their true opinions. It also makes it more difficult to have a rational discussion about the issue. Fear sells and fear of being pejoratized intimidates potential dissenters, even Mr A.I. Bot takes a less than even-handed view of the unconvinced:

Climate change deniers, also known as global warming deniers, are individuals or groups who deny, dismiss, or express unwarranted doubt about the scientific consensus on climate change. They dispute the evidence that human activities, such as burning fossil fuels, are causing significant changes in the Earth’s climate. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence on the matter, there are still elected officials, including 109 representatives and 30 senators, who deny the scientific evidence of human-caused climate change in the US Congress.

So how does this psychosis spread? By becoming an institutionalised cultural norm. For the origins of this we must look to the environmental movement.

The history of environmentalism

The concept of living in harmony with nature dates back to ancient times when early human societies such as the Indus civilization managed waste and sanitation to prevent pollution and its impact on human health. The roots of modern environmentalism can be traced back to England in the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution brought about significant changes to the landscape, and many people were concerned about the impact of pollution on their health and well-being.

The natural history movement viewed nature as evidence of the existence of God. During the Victorian era, there was a belief that human progress and survival necessitated mastery over the environment. However, by the end of the 19th century, a bio-centric conscience emerged, emphasizing the moral duty of citizens to protect the environment.

This included the formation of organizations like the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and the National Trust, which sought to protect the natural environment. These organizations were instrumental in shaping public opinion and promoting the idea that the natural world was something to be cherished and protected.

Animal agriculture is the leading cause of global warming,

Alisdare Hickson – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Environmentalists campaigned for preservation, starting with cruelty to animals and expanding to include the amenity movement, which led to the creation of natural reserves and the founding of the National Trust in 1893. The movement matured post-World War II, with single-issue campaigns evolving into protests for the defence of biotic health. Notable environmental crises such as the Great Smog of 1952 and the Torrey Canyon oil tanker spill in 1967 captured public attention.

Over time, environmentalism became more politicized, and the focus shifted to global issues like climate change. Today, many people view environmentalism as a moral imperative, and those who question the mainstream narrative are often stigmatised as immoral or unethical. Has environmentalism, therefore, become a religion?

Environmentalism as a religion

One of the most striking features of mass psychosis is the way that it can resemble religious belief. Religion can, and mass psychosis does, involve a deeply-held faith in a particular idea or ideology, often with little or no empirical evidence to support it.

In the case of global warming, some activists have referred to it as a “secular religion,” certainly some people have incorporated environmentalism into their spiritual or philosophical beliefs. This is because it involves many of the same elements as traditional religion, including a moral imperative, a sense of community, and a belief in something greater than oneself.

Traditional religious affiliation also plays a role in people’s views on climate change. In the United States, Evangelical Protestants are the most sceptical religious group, with many citing larger issues or believing that God is in control of the climate. The fastest-growing group in surveys asking about religious identity are the religiously unaffiliated, who tend to express higher levels of concern about climate change compared to other religious groups.

Political affiliation also heavily influences views on climate change, with the Right traditionally less likely to view it as a serious problem compared to the Left. No matter what your religion and politics it’s difficult not to acknowledge that a set of environmental issues and assumptions are presented to us in the West as if culturally normative in the way that established religion was prior to this more secular age.

How the brain forms beliefs

Belief formation is a complex process that involves many different factors, including personal experience, social influence, and cognitive biases. When it comes to global warming, these factors can interact in complex ways, leading to the formation of deeply-held beliefs that may be resistant to change.

One factor that can influence belief formation is confirmation bias. This is the tendency to seek out information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs and ignore information that contradicts them. In the case of global warming, people and media may seek out information that supports their belief in the issue and ignore information that challenges it.

Another factor is the ‘availability heuristic’, which is the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events that are easy to recall. This can lead people to overestimate the impact of environmental problems like hurricanes or wildfires, even if the actual data suggests otherwise.

Cultural norms created through propaganda

Propaganda has long been used to shape public opinion and create cultural norms. It is a powerful tool that can be used to manipulate people’s beliefs and behaviours, often without their knowledge. In the case of global warming, propaganda has played a significant role in shaping the public’s perception of the issue.

One example of this is the use of scare tactics to promote environmentalism. Many environmental groups use images of polar bears stranded on melting ice caps or flooded cities to create a sense of urgency and fear. While these images may be based on real environmental concerns, they are often exaggerated or taken out of context to create a sense of panic.

Bear global warming no go,

Monado – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Language is used to frame the issue in a certain way. In the Guardian newspaper the term ‘warming’ has been replaced by ‘heating.’ Phrases such as ‘climate emergency’ and ‘climate breakdown’ have been invented, disseminated, promoted and normalised.

The media plays a significant role in shaping public opinion, particularly when it comes to issues like global warming. News stories that focus on the negative impacts of climate change can create a sense of urgency and fear, leading some people to support more extreme solutions.

While it is important to inform the public about environmental issues, the media can also contribute to the spread of misinformation. Stories that are based on anecdotal evidence or personal opinion can be presented as scientific fact, leading to overreaction and panic.

Propaganda is a communication tool that aims to influence the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours of a target audience. Although there are as many or as few propaganda techniques as are needed to deliver the required effect, some of the more obvious principles are listed below. Readers will be able to fill in the blanks regarding global warming/climate change narrative strategies.

- Simplification: Propagandists simplify complex issues into simple messages that are easy to understand.

- Emotional appeals: Propagandists use emotions to create a positive or negative response to a message.

- Name-calling: Propagandists use negative labels to create an unfavourable image of a person, group, or idea.

- Assertion: Propagandists repeat a message over and over again, without providing evidence, until people believe it to be true. (How many times have you heard Puffins say, ‘It’s relentless.’)

- Bandwagon: Propagandists create the impression that everyone is doing something, and you should too.

- Plain folks: Propagandists present themselves as ordinary people, just like their audience.

- Testimonials: Propagandists use endorsements from famous people or experts to support their message.

- Transfer: Propagandists use symbols, images, and other associations to transfer positive or negative feelings to a person, group, or idea.

It is important to be aware of the principles of propaganda so that you can recognize it and make informed decisions based on facts and critical thinking.

The impact on policy

Mass psychosis can have significant implications for policy decisions, particularly when it comes to issues like global warming. When a particular belief becomes a cultural norm, policymakers may feel pressure to support it, even if the evidence suggests otherwise.

This can lead to irrational policy decisions that are based on fear and self-interest rather than reason. For example, some policymakers have advocated extreme measures such as banning fossil fuels, abolishing central heating and ending personal transport, even if these measures are not supported by the data.

In conclusion, mass psychosis is a complex phenomenon that can have significant implications for our society. When it comes to global warming, it can lead to irrational decision-making, stigmatization of dissenters and a culture of fear.

By understanding the root causes of mass psychosis, we can better address the issue, real or imagined, of climate and the resulting policy decisions’ impact on our world. This means promoting rational discussion, challenging propaganda, and encouraging independent thought. Only by doing this can we hope to create a sustainable future for ourselves and future generations.

Whether this can be achieved in the present febrile atmosphere before irreparable harm is done remains to be seen. Arguably a post-Enlightenment Age of Reason has been ended by the recent emergence of instant, hysterical, ubiquitous and emotion-driven global communication. As Frau Junge also said when reflecting upon the pre-war experiences of her generation, “A madness had descended.”

© Always Worth Saying 2023