18th Summit of Non-Aligned Movement gets underway in Baкu,

Press Service of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

Flash, bang stuff

Last week, we visited British Guiana for our Railway Review and, as is sometimes the case, found ourselves in the wrong place but at the right time. We tootled along some 15 miles of sugar-plantation iron road, consulting Major F. von Bouchenroeder’s Batavian map all the way to the wooden staithes at Parika – land once owned by 18th-century Demerara sugar magnate John Daly. Meanwhile, the flashy, bangy stuff was going on next door in Venezuela.

As the ink was drying on another unread article – telling of Dutch settlers and Chinese indentured labour – the modern day was intervening in the shape of a Delta team relieving Venezuela of its president and his wife. US special forces captured Nicolás Maduro in a pre-dawn military operation in Caracas last Saturday and flew him to New York to face narco-terrorism charges. Maduro, who claims he is kidnapped, pleaded not guilty in a Manhattan federal court on Monday.

Although this article was supposed to be a Railway Review concerning the possible presence of a Pechot prefabricated railway in the jungles of French Guiana, we shall pop next door in the other direction, and be topical and newsy rather than esoteric and niche. Not going to lie, this humble scribe is not familiar with the territory, but can inform the reader that in the east of Venezuela two railway lines connect the mighty Orinoco with iron-ore deposits.

Rail, ore and hydro

A line from Cerro Bolívar runs to Ciudad Guayana on the banks of the river, as does another to the east from Upata. As ever, a knowledge of railways and their history is transferable and helps us to understand what is happening now. The line from Cerro Bolívar to Ciudad Guayana in southeastern Venezuela hauls high-grade iron ore from the Cerro Bolívar mine to steelworks and export facilities near Ciudad Guayana and Puerto Ordaz. It forms part of the CVG Ferrominera Orinoco freight network, transporting millions of tonnes of ore for domestic use and export.

© Google Maps 2026, Google licence

In doing so, it follows the flooded valley of the Caroní River, a tributary of the Orinoco containing hydroelectric plants. Despite being a dot on the national map, as the fish swims it is 119 miles long, giving us an idea of the size of the country. At 354,000 square miles, Venezuela is seven times bigger than England. A population of 28 million is concentrated close to the coast, around the capital Caracas, and in the far west of the country where the oil lies. Or rather, in the far west where the oil reserves are being exploited.

Maracaibo oil

The oil-producing area is easy to spot on the map as it is centred around Lago de Maracaibo near the border with Colombia. An estuary rather than a lake (if it were a lake, it would be the largest in South America), a narrow opening joins 5,000 square miles of fresh water to the sea. The mouth was dredged in the 1930s and a two-mile-long breakwater constructed. As a result, the waters of the northern part of the estuary turned from fresh to brackish and, more importantly, ocean-going tankers could enter the lake to access inland oil terminals.

The Maracaibo oil field was discovered in 1914, with the first well drilled three years later. Large-scale production began in 1922. The fields are concentrated along the lake’s northeastern and northwestern margins, where (those who understand such things inform us) hydrocarbons occur in Tertiary sandstones and Cretaceous limestones. The productive area covers around 500 square miles within a belt of coastal waters on the eastern side of the lake measuring 65 miles in length and 20 miles in width.

On the northwestern shore lies Maracaibo, the capital of Zulia State, Venezuela’s second-largest city, and one of the world’s major oil export ports. The early development of the field was driven by foreign oil companies, with a strong American and European presence. The original Creole Petroleum Corporation came under the control of Standard Oil of New Jersey. Royal Dutch Shell, through subsidiaries such as Venezuelan Oil Concessions Ltd., also played a major role in early exploration and development, including significant discoveries like the La Rosa field.

© Google Maps 2026, Google licence

Untapped potential in the Orinoco Belt

All very interesting. However, when in the modern day our curiosity is pricked by commentators referring to Venezuela as having the largest oil deposits in the world, we must head back east, to the Orinoco and the likes of Ciudad Guayana. About them sits the massive Orinoco Oil Belt, underdeveloped as a result of several interlinked factors, including the difficult nature of its extra-heavy crude, prolonged economic mismanagement, chronic underinvestment in the state oil company, and the effects of international sanctions.

The oil itself is heavy and viscous, with a high sulphur content, making it far more complex and costly to extract, transport, and refine than conventional light crude. Production requires blending with lighter oils or imported diluents, adding further expense and logistical difficulty. At the same time, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) suffers decades of underinvestment, poor maintenance, and infrastructure decay. Rather than reinvesting revenues into field development and technology, successive governments under Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro diverted funds toward social programmes, political priorities, and their own bank accounts, thus eroding the company’s technical capacity.

© Google Maps 2026, Google licence

This is compounded by political and institutional instability with nationalisation, resource nationalism, and repeated purges of experienced managers and engineers hollowing out institutional knowledge and deterring foreign firms with the capital and expertise needed to develop such complex reserves. U.S. sanctions have further constrained Venezuela’s access to international finance, specialist equipment, and the diluents required to process heavy crude, limiting export options and accelerating a collapse in production. Meanwhile, prolonged political and economic turmoil drives a sustained brain drain, with skilled oil workers leaving the country and further weakening operational capability.

All of this may change through new investment under The Donald’s stewardship. Or it may not.

Corruption

This takes us back to the iron ore industry and the hydroelectric schemes along the Coroni River. The Caroni is Venezuela’s second most significant river and a cornerstone of the country’s hydroelectric power generation. It has one of the world’s most developed cascades of dams, all operated by state-owned companies such as CVG-EDELCA.

The most prominent of these is the Guri Dam, a massive structure completed in stages between the 1960s and the 1980s with an installed capacity of over 10,000 MW. This makes it one of the largest hydroelectric plants on the planet and a crucial source of electricity for Venezuelan industry and its national grid. But there is a but.

The Tocoma Dam project on Venezuela’s Caroní River became emblematic of the country’s infrastructure struggles. Budgeted at around $3.1 billion, its cost had ballooned to $9 billion by 2018, with an estimated $1.5 billion thought siphoned off through corruption involving government officials and a Brazilian construction consortium. As a result, the dam and associated power plant were never completed, and the stalled project now stands as a high-profile example of how cost overruns, mismanagement, and graft have undermined Venezuela’s electrification ambitions.

© Google Maps 2026, Google licence

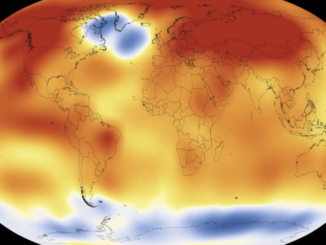

Venezuela’s hydroelectric system has also been tested by environmental and operational challenges. The Guri Dam faces reduced reservoir levels during droughts exacerbated by climatic variability, such as El Niño events, contributing to widespread energy shortages and rolling blackouts. Operational reliability has been further weakened by ageing infrastructure, insufficient investment, and broader systemic issues, leaving the hydroelectric network vulnerable when water inflows decline and demand remains high.

Yes, the country with the world’s largest deposits of hydrocarbons and abundant hydroelectricity suffers blackouts. As for those foreign investors…

Nationalisation

In the early 1970s, Venezuela began asserting control over its energy resources. In 1971, under President Rafael Caldera, the government passed a law to nationalise the country’s natural gas sector. This trend toward resource nationalism continued under Carlos Andrés Pérez, whose economic programme La Gran Venezuela championed sovereign control of strategic industries. As part of that agenda, the oil industry went into state hands on 1 January 1976, when the government created the state‑owned PDVSA to run the sector and replace foreign concessionaires.

At the same time, the iron and steel industries were also targeted for nationalisation. The iron ore sector came under control in the mid‑1970s as part of the same drive to capture more value from Venezuela’s natural resources. Decades later, President Hugo Chávez expanded this approach. In the late 2000s, his government nationalised a series of iron and steel firms, bringing them into government‑run ownership as part of a broader socialist industrial strategy.

These moves aimed to consolidate national control over strategic sectors and redirect revenue toward domestic priorities and the Chávez family. However, the long‑term outcomes have been mixed: despite initial support from some workers, many of the nationalised enterprises have struggled with declining production and limited investment, contributing to broader challenges in Venezuela’s industrial and energy sectors.

This is the tar pit of corruption, politicking and inefficiency that The Donald chooses to dip his private parts into.

We wish him luck.

© Always Worth Saying 2026