Introduction

In March 2024 I purchased a first generation, Birmingham-made Parker-Hale replica of a Whitworth military pattern muzzle-loading rifle of the late 1850s. These iconic rifles gained legendary status following their use in the American Civil War of 1861-1865 by Confederate sharpshooters. Genuine examples of military and civilian Whitworth target rifles of the period occasionally crop up at auction but those that are shootable tend to go for eye-watering prices leaving replicas as the only practical route to Whitworth ownership for the majority of enthusiasts. Even among replicas, however, there is a hierarchy of desirability as when Birmingham gunmakers Parker-Hale ceased trading in the early 1990s all their existing stocks of barrels, parts and manufacturing machinery were purchased by the Italian company Armi San Paolo who later produced ‘Parker-Hale’ rifles under the Euroarms brand. These second generation rifles are generally considered to be of inferior quality and hence are less sought after by shooters. The Italian reproduction arms manufacturer Davide Pedersoli now produces an excellent Whitworth replica that retails for £1,789 at the time of writing.

Due to the way in which it was used in the American Civil War, the Whitworth rifle is now generally considered to be the first true sniper rifle.

The Early Years

Sir Joseph Whitworth, Baronet, FRS, FRSA was born in Stockport, Cheshire in December 1803 the son of a teacher who later became a Congregational minister. Whitworth’s interest in machinery and his aptitude for practical mechanics first became evident when he left school to became an indentured apprentice to his uncle, a Derbyshire cotton spinner, originally with a view to his eventually becoming a partner in the business. While Whitworth was fascinated by the workings of the factory machinery, he soon became critical of its lack of accuracy and precision becoming convinced that he could make a much better job of it himself.

After completing his four-year apprenticeship Whitworth left his uncle’s employ to work as a factory mechanic in Manchester for another four years before moving to the London premises of Henry Maudslay, a machine tool innovator, where he became interested in the concept of the flatness of surface plates.

Maudslay had demonstrated that perfect flatness is central to the philosophy of precision as by being perfectly flat, a surface plate can give precision to other things that are measured against it and thus be declared to be ‘true’ or not; ‘precisely made’ or not. In time the two men began to squabble as to who had originated this concept and how to achieve it. With the benefit of hindsight it seems clear that while Maudslay first had the idea, it was Whitworth who originated the means (the use of engineer’s blue and scraping as opposed to polishing techniques) to achieve it. In other words, Maudslay made the machines while Whitworth produced the tools, gauges and instruments to ensure their precision.

In 1833 Whitworth returned to Openshaw, Manchester to open his own workshop where he produced lathes that quickly gained a reputation for both quality and precision. Perhaps the two closely linked achievements for which Whitworth is best remembered to this day are his standardised (British Standard Whitworth or BSW) screw threads for fixing, measuring and moving cutting heads and for his principle of ‘end measurement’.

Prior to Whitworth’s involvement, measurement had been done by comparing an object against a linear scale on a ruler or straightedge but this is fraught with problems. This type of measurement is subjective as it relies on individual eyesight and judgement, for example how accurately is the item aligned with the line on the scale? How thick are the lines and what degree of magnification is needed to see them? Even when using a Vernier scale to make more accurate and exact decisions, good eyesight and fine judgement are still required.

Whitworth’s contribution to the new science of metrology, instead of relying on eyesight, involved the sensation of feel as the item to be measured was first tightened and then released between two plane steel sheets moved by a long, fine screw. When the item fell from the gauge by gravity alone, that was its true measurement. In 1858 and using these principles Whitworth produced a micrometer that could measure to an accuracy of one-millionth of an inch. To put this in context, only 80 years earlier John Wilkinson had initiated the concept of precision engineering by producing a machine that could bore a hole to the then amazing tolerance of one-tenth of an inch.

Whitworth’s Research into Rifle Ballistics

By the 1850s, Joseph Whitworth was known internationally as the foremost manufacturer of machine tools. Exhibiting at the 1851 Great Exhibition his catalogue reads ‘Self-acting lathes, planing, slotting, drilling and boring, screwing, cutting and dividing, punching and shearing machines. Patent knitting machine. Patent screw stocks, with dies and taps. Measuring machine, and standard yard &c.” Nowhere is there a mention of firearms yet in 1854, Lord Hardinge the then Commander-in-Chief of the British Army engaged Whitworth as a consultant with the brief of investigating the mechanical principles applicable to the construction of a more efficient infantry weapon. As he was unwilling to commit to the design of all the machinery necessary to produce a complete rifle, Whitworth’s negotiated brief was to consider constructing the machinery to produce the rifle barrel alone.

Anyone who has a practical interest in rifle shooting today will be familiar with the chronograph, an electronic device that measures the speed of a bullet passing over its sensors. By knowing the weight and speed of the projectile and the standard deviation of the data, calculations can be carried out regarding its down range performance and fine adjustments can then be made to reloading techniques to achieve optimum velocity and consistent accuracy. The latest developments in this technology are the ‘Labradar’ and Garmin units that instead of sensors use continuous wave Doppler radar and advanced digital signal processing technologies to measure velocities continually up to 100 yards from the muzzle, depending upon the size of the bullet.

Unfortunately for Joseph Whitworth, none of this technology was then available so he devised his own brilliantly simple yet effective method of down range bullet-tracking. To achieve this he constructed a roofed and walled gallery in the grounds of his home in Rusholme, Manchester that was 500 yards long, 20 feet high and 16 feet wide. Along its length he erected tissue paper screens through which the projectiles would pass proving as they did whether their points maintained a true forward direction. The positions of the holes in the paper screens also allowed him to calculate the bullets’ trajectories.

Before his research could commence a severe storm tore down the gallery which was rebuilt in 1855. In the meantime however Whitworth had not been idle and in December 1854 he patented ‘Improvements in cannons, guns and fire-arms’ which included the polygonal bore and mechanically fitting projectiles. Neither of these innovations was his own invention and they are now generally acknowledged to have been the brainchild of Isambard Kingdom Brunel who had previously engaged the services of the Birmingham gunsmith Westley Richards to construct experimental rifle barrels to his design but Brunel had never developed the concept further.

At the time of Whitworth’s research, the standard British military rifle was the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket that fired a hollow-based 530 grain .577” pure lead, paper-patched Pritchett bullet that expanded to grip the rifling in the barrel upon ignition of the 70 grain black powder charge. Lord Hardinge had stipulated in his brief only that the current bullet weight and powder charge must be retained.

Whitworth set about experimenting with a wide variety of rifle barrels with different rifling twists, calibres, barrel lengths and metals assessing the projectiles’ stability by the holes the bullets left when passing through the paper screens. From his research, Whitworth determined that optimum bullet performance would be achieved if its calibre were reduced to .451”, its length increased to three times its calibre (i.e. 1.35”) and the rifling twist increased to 1 in 20 inches to stabilise the longer bullet. By comparison the Enfield rifle with its .577” diameter bullet had a slow twist of only 1 in 78 inches. He also recommended that his patent hexagonal rifling be adopted together with a mechanically fitting, paper-patched, hexagonal section bullet that incorporated a twist that precisely engaged the rifle’s bore on loading.

Rifle trials were carried out on the ranges at Hythe in 1857 when Whitworth’s ‘small-bore’ design was proven to outclass the Enfield ‘full-bore’ rifle by a significant factor not only being far more accurate at 500 yards but able to hit a target at 2,000 yards that the Enfield could only hit at 1,400 yards. Despite this, Whitworth’s innovative barrel was never adopted by the British Army as it was found to become fouled with powder deposits much more quickly than its rival while being four times more expensive to produce.

While no large military contract was forthcoming, the Whitworth Rifle Company’s rifles did find favour among the ranks of the Volunteer movement that was founded in 1859 to counter a perceived threat of invasion by France. At the inaugural meeting of the National Rifle Association at Wimbledon in 1859, Queen Victoria had fired the first shot by pulling a silken lanyard attached to a Whitworth rifle mounted in a machine rest hitting a metal target 400 yards away slightly more than one inch from its dead centre.

The value of the prizes (2025 values shown in brackets) competed for at this meeting was £2,238 (£341,026) of which £950 (£144,761) was reserved for the Volunteers, the forerunners of today’s Territorial Army. The prestigious Queen’s Prize of £250 (£38,095) awarded to the premier rifle shot of the year brought international fame to the winner and accordingly the most accurate rifle then available (the Whitworth) was eagerly sought after among their ranks of affluent gentlemen riflemen.

In 1862 Whitworth produced a thousand of his rifles for trials by the military and in 1864 more than eight thousand slightly shorter barrelled rifles were issued to a number of regiments for evaluation. By the 1860s, however, it was clear that the days of the military muzzle-loader were limited and consequently a decision was made by the army to convert its stocks of existing .577 Enfield rifle muskets into breech loaders using the Snider mechanism as a stop-gap prior to the adoption of the 577-450 calibre Martini-Henry in the early 1870s.

The Whitworth Rifle in Confederate Service.

At the outbreak of hostilities in 1861 the Confederate states were desperate to obtain stocks of rifles with which to equip their infantry and their representatives looked towards Europe to satisfy this demand. While impressed by the quality and performance of the Whitworth rifle, the Americans were shocked at the prices being asked. A bare rifle was priced at just short of $100 ($3,800) as opposed to $12-25 ($456 – $950) for an Enfield Pattern 1853 rifled musket. This seemingly exorbitant price soared to $1,000 ($38,000) for a cased Whitworth rifle complete with telescopic sight, 1,000 rounds of ammunition and all necessary accessories.

Somewhere in the region of 300 Whitworth rifles and their accessories were shipped to the Confederacy but it would appear that only 150 or so of these ever arrived due either to mishap en-route across the Atlantic or to the Union blockade of Southern ports. To date none of the missing rifles, which would be easily identifiable by their known serial numbers, has ever been located suggesting that they were indeed lost in transit.

Of the 150 rifles known to have been delivered, around 100 were fitted with side-mounted Davidson telescopic sights which in the hands of carefully selected sharpshooters were used to great effect against enemy gun crews and high-ranking Union officers.

By 1863, the Union forces had developed a fear of the Whitworth rifle with one of their Engineers commenting that,

“The least exposure above the crest of the parapet will draw the fire of his telescopic Whitworths which cannot be dodged. Several of our men were wounded by these rifles at a distance of 1,300 yards from [Fort] Wagner.”

Enemy soldiers would know when they were being sniped at by a Whitworth as their hexagonal bullets made a characteristic whizzing sound that was quite unlike the sound of any other projectile fired at them.

John West, a Georgian in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, wrote that,

“In ‘62 General Lee received thirteen fine English Whitworth rifles that were warranted to eighteen hundred yards. These were the best guns in the service on either side. Thirteen of the best marksmen in the army were detailed for this special service, and I was the only Georgian that was selected. We were placed under the command of General Brown, who had no other duty than to command us. We were practiced three months before going into service. A score of every shot was kept during these three months, and at the end I was 176 shots in the bulls eye ahead of the rest. The last day of practice in marksmanship was tested by our superior officers. A white board two feet square with black diamond about the size of an egg in the center was placed fifteen hundred yards away. The wind was very chilly and it was unfavorable for good shooting, and I put three bullets in the diamond and seven in the white of the board. I beat the record and won the choice of horse, bridle, spurs, gun, revolvers, and sabre. Our accouterments were the best the army could afford. Then we entered active service, and I have been through scenes which have tried men’s souls. I soon became indifferent to danger and inured to hardships and privations. I have killed men from ten paces distance to a mile. I have no idea how many I killed but I made a good many bite the dust. We were sometimes employed separately and collectively; sometimes scouting, then sharpshooting. Our most effective work was in picking off the officers, silencing batteries and protecting our lines from the enemies Sharpshooters. Artillerymen could stand anything better than they could sharpshooting, and they would turn their guns upon a Sharpshooter as quick as they would upon a battery. You see, we could pick off their gunners so easily. Myself and a comrade completely silenced a battery of six guns in less than two hours on one occasion. The battery was then stormed and captured. I heard General Lee say he would rather have those thirteen sharpshooters than any regiment in the army. We frequently resorted to various artifices in our warfare. Sometimes we would climb a tree and pin leaves all over our clothes to keep their color from betraying us. When two of us would be together and a Yankee Sharpshooter would be trying to get a shot at us, one of us would put his hat on a ramrod and poke it up from behind the object that concealed and protected us, and when the Yankee showed his head to shoot at the hat, the other one would put a bullet through his head. I have shot them out of trees and seen them fall like coons. When we were in grass or grain we would fire and fall over and roll several yards from the spot whence we fired and the Yankee sharpshooters would fire away at the smoke.”

The Confederate Whitworth Sharpshooters claimed they killed many Yankee Sharpshooters and didn’t seem to hold Berdan’s in very high regard. It seems they resented all the attention the Berdan’s were getting in the northern press and claimed that Yankee Sharpshooters killed very few Whitworth men and were not as “good shots” as they were.

Perhaps the most famous example of Whitworth sniping during the Civil War took place on May 9th 1864 at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House when following the earlier wounding of General William Morris, Major General John Sedgewick who, ignoring the advice of his Staff Officers not to visit that part of the line, went forward to speak to the men that he had seen ducking at the sound of Whitworth bullets.

According to Martin T. McMahon, Brevet Major-General, U.S.V.; Chief-of-Staff, Sixth Corps, who was present at the scene:

The general said laughingly, “What! what! men, dodging this way for single bullets! What will you do when they open fire along the whole line? I am ashamed of you. They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” A few seconds after, a man who had been separated from his regiment passed directly in front of the general, and at the same moment a sharp-shooter’s bullet passed with a long shrill whistle very close, and the soldier, who was then just in front of the general, dodged to the ground. The general touched him gently with his foot, and said, “Why, my man, I am ashamed of you, dodging that way,” and repeated the remark, ”They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” The man rose and saluted and said good-naturedly, ”General, I dodged a shell once, and if I hadn’t, it would have taken my head off. I believe in dodging.” The general laughed and replied, “All right, my man; go to your place.”

For a third time the same shrill whistle, closing with a dull, heavy stroke, interrupted our talk; when, as I was about to resume, the general’s face turned slowly to me, the blood spurting from his left cheek under the eye in a steady stream. He fell in my direction, I was so close to him that my effort to support him failed, and I fell with him.”

The fatal shot was at the time estimated to have been made from a distance of between 800 and 1,000 yards.

Shooting the Whitworth Rifle

Anyone familiar with a Pattern 1853 rifle-musket with its pour powder down barrel, ram lubed Minié ball on top, cap nipple, cock hammer and pull trigger loading sequence should have no problems loading and firing a Whitworth rifle provided some special bits of kit are available and far greater care is taken with its more complicated loading regime.

Before taking your Whitworth to the range, you will need to obtain a hexagonal punch for cutting out felt and card wads and a special hexagonal brass loading rod tip that is used for scraping fouling from the angles of the bore and for swabbing out between shots. If you want to shoot period-correct hexagonal, mechanically fitting bullets you will also need to buy an expensive bullet mould and source a supply of 100% rag onionskin paper for patching them. This once common paper is now hard to find and likely to be very expensive indeed.

Fortunately, heavy 530 grain cylindrical pure lead bullets also work well in the rifle as they swage into a hexagonal cross section as they travel down the barrel.

The best bullet appears to have been the British military straight-sided cylindrical, hollow-based, paper-patched round that was developed for the trials in the late 1850s but at the time of writing I have been unable to find a source for such a mould.

Another peculiarity of the Whitworth is that it has a ‘patent breech’. At the breech end of the barrel there is a reduced diameter powder chamber which is said to aid ignition and improve the burning of the main powder charge resulting in higher pressures being generated and thus higher muzzle velocities. The increased blast produced rapidly erodes ordinary nipples to the point where pressures are drastically reduced so a special, platinum-lined nipple that will last for thousands of shots is essential. Mine cost £100 plus postage. Who said that shooting antique guns is a cheap hobby?

So, once you have cut out a load of card wads with your hexagonal punch (beer mats are ideal for this); cut out a supply of square, cloth cleaning patches half of which are slightly dampened (I use Windolene spray with added vinegar for this); punched out a supply of thick, hexagonal felt wads that you have soaked in a 50:50 mix of molten beeswax and animal tallow; carefully measured some powder charges into plastic vials and cast, sized and lubricated a load of pure lead bullets – you can finally go to the range.

The first thing you have to do when the range goes live is to swab the bore with a dry cloth patch to remove any oil deposits and then snap a couple of caps on the empty rifle to clear the nipple and ignition channel of oil residues. Now you can load the rifle by first pouring a measured amount of powder down the barrel followed by a hexagonal beer mat wad. Next a lubricated felt wad is pushed down on top of the card wad followed by another card wad. Before loading the bullet, the wad stack is pressed down firmly but without crushing the powder granules. The bullet which has been pre-sized to .451” is then pushed (not rammed) down the bore. The rifle can now be capped and fired.

This procedure is repeated but with the added complication of cleaning the bore carefully between all subsequent shots. Once the powder and wads have been loaded, the bore must be swabbed out with a moist cloth patch on the hexagonal cleaning rod tip making three or four passes up and down the bore. This is then repeated with a dry patch after which a bullet can be loaded as previously described. You would be surprised just how much black powder residue is removed during this absolutely essential cleaning process.

It is perhaps now obvious why this supremely accurate wonder weapon was never adopted by the British army and why only the most intelligent and gifted marksmen in the Confederate army were entrusted with its use and care.

But is it worth all this faffing about?

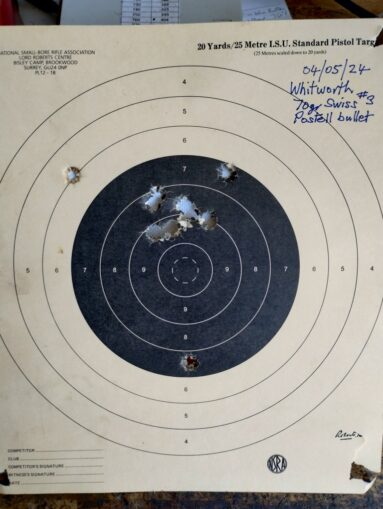

That of course is a matter of opinion and down to personal preference. I regularly have fellow shooters watching me load and fire the Whitworth, most commenting how much they admire my dedication to replicating Victorian muzzle-loading techniques whilst expressing no desire whatsoever to do it themselves. Those who take up the offer of shooting my rifle are generally surprised and impressed by its kick with only 70 grains of Swiss No.3 powder behind the heavy bullet. Out on the ranges at Wimbledon in the 1860s our Victorian forefathers would have used a minimum of 90 grains of the finest quality Curtiss and Harvey black powder (and frequently more) when competing at 1,000 yards and beyond. Shooting prone and self-supported these loads must have given them a fearsome wallop in the shoulder and cheek every time they fired.

The reputation of the Whitworth has been so hyped that it is natural to assume that it will be easy to put every bullet through the same hole right from the start. Nothing could be further from the truth and only recently two friends who each own an original Whitworth have sought my advice as they were having problems even getting their rounds on paper at 50 yards. Both seemed surprised when I shared the original loading techniques with them. Shooting the Whitworth isn’t difficult but it does require consistency of loading and close attention to detail which clearly was lacking in both their approaches.

All that now remains is for me to modify my foresight so as to lower the point of impact and then I’ll be able to get down to some serious shooting with this beautiful historic rifle.

© text & images except where indicated; Tom Pudding 2025