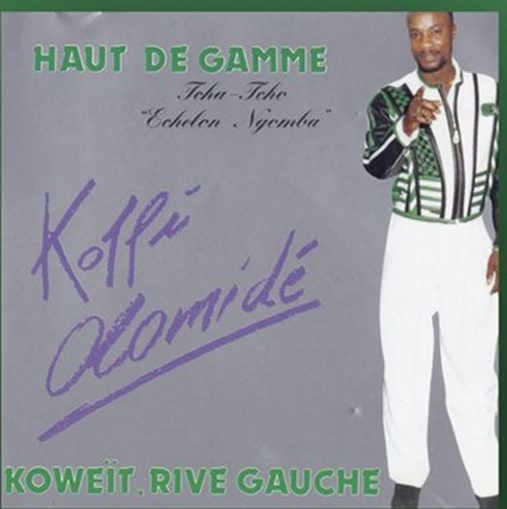

Haut de gamme (“Top of the line”) is an apt title for an album by Koffi Olomide; a man who, in 2001, said of himself “I am different, I have class”. Quite.

Haut de gamme, his 1992 offering issued when the DRC was still under dictatorial rule and known as Zaire, oozes, brims and overflows with the musical offerings western listeners have come to expect from “African” music: cutesy high-fretted guitar riffs endlessly repeated; synthesised drum beats; and calls and answers in local dialects (in this case Lingala mostly).

To give Olomide his credit, he croons cliches over tight musical outputs akin to the strongest cheddar dripping in honey (see song Elixir). Accusations of musical self-indulgences wouldn’t be amiss here: the shortest track comes in at 4:51 with six out of the nine clocking in over the 6:30 mark.

Admittedly, 1992 wasn’t the best year for Zaire: spiralling inflation, internal tensions and external disputes were threatening the already-weak stability of an impoverished and troubled nation, although it would be another five years until Seko would flee the country to spend the few months of his short exile abroad before dying in Morocco.

In this context, opening track Papa Bonheur / Father Happiness makes complete sense: a proverb-laden invocation of Dieu le Pere…calling on the telephone. The stardom of Olomide, with tours outside even Africa, provides comparisons and context for his beloved fellow Congolese (When I arrived in Dusseldorf…. when I arrived in Geneva…when I got to Paris….I just heard the news. That Kinshasha, no matter what, in my name). “The news”? “Hello Dad happy on the phone…soldiers come” perhaps.

A smidge over seven minutes later takes us into the synth-led slow number Desespoir (Despair) with progressive minor chords underlying guttural vocalisations before Olomide’s singing comes in dark, slow and pained. Singing of whom, exactly? A love unrequited? Lost? He sings “mua bana, wa baba”: My children, you’re bitter”. The overt Christian imagery typical would lead us more toward a religious interpretation than personal; however as the song plods onwards (it’s not likely one you’d listen to specifically and repeatedly, despite it being the highest played song off the album on Spotify – as of Aug 2022 clocking in at 367,000 plays) there’re many name drops: Mathy Masongi, Nono Lomboto, Beniko the Wolf, Willy Mamoma, Tity the Devil….

Following Desespoir, Koweit Rive Gauche offers, despite the enigmatic title, a clearer meaning. Over a beautiful looped guitar riff and simple beat with a shaker of kind, we are told “Ever since you came, into my life, Angie, my heart seems pretty small, To contain, all the love I carry, Come back!”. It’s cute stuff.

Seek and you shall find!, or more accurately, Qui Cerche Trouve follows. Less Westernised, a female choir provides a response to various proverbial calls: the rope of life is in god’s hands (Singa oy’a la vie eza na maboko’a Nzambe); God will not leave you he will give you a hand (Nzambe akotika yo te akopesa yo loboko); Let my name be sweet in people’s mouths (Mokolo’akufa na nga okozala olela ngai).

The album continues in similar vein whether in Lingala or French with Elixir for example containing some fantastic cliches of a ‘wild haired’ and ‘fiery-eyed’ love. Money and its corrupting force is a key message within Porte-Monnaie but frankly by this point the same pace, BPM of the electronic drums and lack of much variety is starting to bore. Olomide doubles down though, with the final three tracks clocking up just shy of twenty minutes of playtime.

In our world of quantity and ease of variety it is easy to forget this wasn’t always the case. In central Francophonic Africa in the early 90s, a radio serenading kerb-kickers and queues of waiting patrons outside endless rows of coiffeurs would’ve graced the ears with this album. Seven minutes then is different to seven minutes now. In a fragile country, with pitiful employment figures and hyperinflation (1992 saw the introduction of a Z5,000,000 denomination with devaluation of the currency going from US$1 being worth Z114,000 around March 1992 to Z2,000,000 by the end of the year) what difference would a couple of minutes make in a song preaching better times, salvation, lost love.

And that therein likely lies the charm of the album on the whole. Listening to Haut de Gamme with the luxury of 30 years’ distance and associated development, it’s not just of a time, age and culture far beyond the grasp of any modern Western listener, it is similar to a naïve gap-yah NGO going off to build a school later raided for its roofing sheets and furniture-firewood. Who are we to sit back and critique and judge it now?

For all its Lingala-based inaccessibility the first half of the album stands up and provides the Kwasa-kwasa hip jiggling and guitar refrains we want and expect. And for that it should be more than applauded. A listener closure in culture and language will get more out of the second half than us, but then they’d not likely be reading this. For the genre this falls under, (grotesquely broad “African”) it will provide what you expect, and you’ll feel the happy-go-lucky approach that characterises the continent. But beyond that, you’re unlikely to ever really pull it off the shelf and listen through time and again; because, quite simply, you aren’t ever going to connect well enough to it. So don’t be that gap-year student thinking it’s all wonderful and sooo interesting. Give it a spin, let it put a smile on your face and, like the opening track of Dieu de Pere calling you up on the telephone, don’t take it or yourself too seriously.

Koffi Olomide – Haut de Gamme

© Cromwell’s Codpiece 2023