Dartmoor

Brat Tor, Dartmoor,

Aidan Tor, Dartmoor – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Dartmoor is a vast, ancient landscape located in the county of Devon. Covering 20 miles by 14 miles, the 80,000 acres of extensive hilly district in the western part of the county are known for their rugged moorlands, granite hilltops (known as tors) and vast wildlife, making it a paradise for outdoor enthusiasts. Dartmoor National Park, established in 1951, four years after my grandparents’ West Country road trip, spans over 368 square miles, offering a rich blend of cultural heritage and natural beauty.

The area is steeped in history, with numerous archaeological sites from the Bronze Age, medieval villages and remnants of its tin mining past. Dartmoor is also home to the famous Dartmoor ponies, a hardy native breed.

Princetown is a small Dartmoor town known for its rich history and scenic surroundings of vast moorlands, tors, and wildlife and for housing the National Park Visitor Centre. It lies nearly in the centre of this desolate district, on a gentle declivity fifteen miles from Plymouth and seven from Tavistock. A popular spot for tourists wanting to learn more about the local wildlife and Dartmoor’s unique geography, in the vicinity you’ll find the Foggintor Quarry, St Michael and All Angels’ Church and several stunning outdoor areas including Bellever Forest and Wistman’s Wood.

Other nearby attractions include Dartmoor National Park, River Dart Country Park, Ashburton Antiques Trail and the South Devon Railway, which offer a diverse range of experiences for visitors. From historical explorations to outdoor adventures, Princetown in Devon offers something for everyone. It is also home to Dartmoor Prison.

Dartmoor Prison

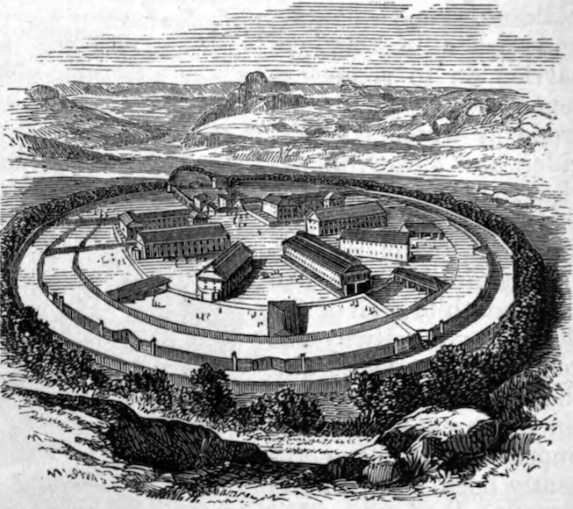

Dartmoor Prison has a full and complex history that spans over two centuries. The prison was originally constructed between 1806 and 1809, mainly to house thousands of prisoners of war during the Napoleonic Wars. The project was designed by Daniel Asher Alexander and was built using local labour. The first prisoners arrived on 22nd May 1809 and by the end of that year the prison was fully occupied.

An 1810 article in The Pilot newspaper described the Royal Prison of War, Dartmouth, as one of the most extensive establishments of the sort in the kingdom, dedicated to the kind treatment and humane attention to the unfortunate victims of war. Apparently, every comfort was administered to alleviate the prisoners’ unhappy lot by the resident agent, Issac Cotgrave Esq. An expenditure of £200,000 had provided a solidity of fabric, security and convenience. The structure was of stone that the neighbourhood afforded in great quantity. A circular perimeter consisted of iron railings surrounded by two solid walls.

Drawing of Dartmoor prison,

Unknown artist – Public domain

Within this were contained 6,000 prisoners wearing a conspicuous yellow and blue striped uniform which made escape impracticable. As well as turnkeys the prison was guarded by between five and six hundred soldiers attached to a barracks about a quarter of a mile to the south of the prison.

Manned in rotation by regiments based in Plymouth, the men guarded Broadmoor in two month-long postings. In anticipation of the end of the Napoleonic wars, it was intended to turn Broadmoor into a conventional prison with the convicts being used for labour on the moor, in the nearby quarries and in an attempt to turn the surrounding wilderness into farmland.

In April 1813 American prisoners began arriving as a result of the ‘War of 1812’ conflict between the United States and Great Britain. Already overcrowded, there were outbreaks of pneumonia, typhoid and smallpox that killed more than 11,000 Frenchmen and 271 Americans. Their graveyards and memorials are at the rear of the prison. When the wars finally ended the PoWs were repatriated, with the prison closing in early 1816.

Dartmoor Prison – the historic main gate,

Neil Theasby – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The incarceration of the Americans was not without its lighter moments. Sir Issac Coffin, a worthy baronet, arrived at the prison to facilitate the release of his wayward American colonial relatives who bore the same surname. Amongst the inmates was a black prisoner who also wished to claim his liberty from the purse of Sir Issac.

‘How old are you?’ asked the Baronet.

‘Thirty, Sir,’ replied the hopeful captive.

‘You’re not from my branch of the family,’ Sir Issac quipped, ‘We don’t turn black until we’re forty.’

From 1815 to 1850, the prison sat empty. In May 1846, Samuel Pym the admiral superintendent of Devonport dockyard addressed a newspaper advertisement to iron-pounders, soap-boilers and builders. An auction was to be held at the site of the late prison. Valuable materials were to be sold by auctioneer Mr D H Hainsselin comprising; forty tons of cast and wrought iron, 24 large cast boilers (suitable for soap boilers), chandeliers, several thousand bricks, 1,300 fire bricks, several thousand feet of floorbaord and much, much more.

With the kind of foresight the Navy is famous for, a few years later the stripped-bare prison was reopened. The new prisoners were put to work. By 1887 they were making boots and great coats for the Metropolitan Police and seaman’s sacks, coal sacks and hammocks – by the thousand – for the Navy.

War time and austerity

During the First World War the prison was designated as a government labour camp. Convicted criminals were removed and replaced by about 1,000 conscientious objectors, those whom tribunals of exemption had allocated non-combat duties in camps on moral or religious grounds. A fairly relaxed regime, the conchies were allowed unlocked cells, to wear their own clothes and to visit the nearby village in their off-duty time.

Warders acted as supervisors only. Even though, the objectors suffered hardship with both they and their families being generally despised. Despite the relaxed conditions, the conchies went on strike in February 1918 in protest to the death of a comrade, H W Firth, over their indignation of his treatment in the prison hospital. A jury disagreed. Satisfied with the man’s treatment, they returned a verdict of death by natural causes.

Besides Coffins and the unfortunate H W Firth, inmates have included (Puffins will be pleased to hear) Eamon de Valera, one of 62 Irish nationalist prisoners confined following Dublin’s 1916 Easter uprising. During questions in the House of Commons, the then Home Secretary stated that 40 Broadmoor Fenians were employed in mailbag making, 18 in halter making and four were in hospital.

Released in June 1917, the following month De Valera was elected MP for East Clare. In a recollection that makes this author feel very old, De Valera was president of Ireland when I visited Dublin for the first time. While fact-checking on Wiki I couldn’t help but notice that O’Connell Street’s Nelson’s column was still standing too. Time doesn’t pass, it flies. Rather like the good admiral when subsequently his column was blown from beneath him by the IRA.

Post war

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

Nineteen-forty-seven, the year of my grandparents’ visit, was an interesting year for the prison. Dartmoor became a military as well as a civilian establishment. In April the borstal institution on the site closed. Military prisoners numbering about 200 remained with a proposal to also house about 150 recidivist (i.e. re-offending) convicts. The future of the prison was ‘under consideration’.

There were demonstrations amongst civilian prisoners regarding the potato ration. A Cecil Elvin Davies escaped and was on the run for 20 days before being caught in his native South Wales having navigated 200 miles while a fugitive. His was the eighth recent escape, another had absconded at Tavistock railway station during a transfer. A military prisoner had made a break in the early summer.

As for my grandparents’ photograph, it must have been taken from Tavistock Road, beyond the village of Princetown and just past the prison’s distinctive main gate. You can have a look around here. Then as now, an austere edifice of 19th century correctional architecture dominates the neighbouring farm buildings.

© Google Street View 2023, Google.com

To the right in the old photograph can be seen the back end of a pony. I wonder if it was one of the famous Dartmoor ponies? If so, it was an austere time for him too. During harsh post-war winters, the ponies were reported as starved of food, half-frozen and in a desperate plight. In February 1947 a relief expedition including vans loaded with fodder was rushed to their aid. Some of the ponies’ tails were found to be frozen stiff and gnawed raw by starvation.

Supt G Planton of the Bristol branch of the People’s Dispensary For Sick Animals trampled the moors bringing them aid between making SOS appeals to local farmers for more supplies of fodder. He explained to the newspapers, ‘I round up the ponies and drive them down towards the road where I spread out hay for them. Their condition is pathetic.’

In the intervening seven decades, according to the prison website, much has changed. The bad old days are gone with no more quarrying or digging barren moorland by hand under armed guard. Even brutal punishments have been abolished. The prison now holds low-category prisoners, encouraged to undertake training programmes to help them on their release.

‘Skilled advisors hold discussion sessions to make them aware of how unacceptable their crimes are. They are not here to be punished; their punishment is loss of liberty tempered by help towards reform and rehabilitation.’

Drowning in Woke, the cons yearn for the days of cholera, potato shortages and raw tails being chewed by famished ponies.

© Always Worth Saying 2023