Public Domain

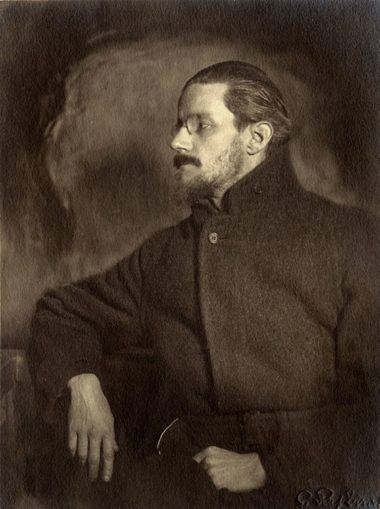

One of the greatest literary works of the age, James Joyce’s “Ulysses”, reveals its author’s surprising, yet profound, understanding of some of the most basic issues in economics. In the early days of the 20th century, when living with his sister in Trieste, near Venice, she told him that the city had 21 cinemas; whereas Dublin, a European city with a population of 350,000, had no cinemas at all. Indeed, two other cities in Ireland, Cork and Belfast, likewise had no cinemas.

With true entrepreneurial insight Joyce recognised the commercial opportunity that this presented, and he decided to open Ireland’s first cinema. However, he had no money and knew that he would need to secure financial backing – which he quite easily achieved in the commercial milieu of Trieste. As vividly described in an essay by economist David McWilliams, Joyce returned to Dublin and initiated negotiations with landlords, discussed designs with painters and decorators, film choices with distributors, fabric for cinema seating, projection methodology – and competitive pricing. He talked to newspapers and journalists about publicity and reviews, and familiarised himself with the attributes of a successful cinema. This assiduous research and implementation guaranteed that the opening night of his “Volta Picture-Theatre” in December 1909 was a sell-out event.

Joyce didn’t merely recognise the opportunity – it was, after all, obvious both to him and his backers. He exploited it by innovating, that ubiquitous feature of economic success recognised by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter 100 years ago. Schumpeter termed the process creative destruction, which he described as a “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one”. In this instance, of course, there was no earlier cinema to destroy but, in Ireland, independent thought and diversity were venerated, society was non-judgmental and favoured rationality over rules – and that was enough to demonstrate Schumpeter’s principle in action. Joyce created something completely new, requiring capital in the form of savings – not necessarily his, but the savings of his backers, and their trust.

And there’s more…..

In Ulysses, Joyce’s anti-hero, Leopold Bloom, takes the next fundamental step: he sizes up the money-making potential of running a tramline down the street from O’Rourke’s Bar and concludes that “property values would go up like a shot”. In fact Bloom recognised the very same insight as that of the contemporary economist Henry George, outlined in his popular book “Progress and Poverty”, a best-seller in America and admired by Shaw and Tolstoy. Central to George’s thinking was the observation that public investment, such as a new tramline placed where it would yield maximum return, enriches private property owners who have contributed nothing towards its cost, rather than the general citizenry. This troubled Bloom: (i) Who should finance public investment? And (ii) who should benefit from it? The taxpayer or the property speculator?

By way of illustration, when the American West was opened up between 1850 and 1900, four out of the five transcontinental railroad companies received land grants from Congress on which tracks were laid and eventually sold, the proceeds of which enabled those companies to finance their railroad construction.

This was also the funding model that facilitated Hong Kong’s sophisticated mass-transit infrastructure: the incremental gains in property values were taxed as the obvious means of paying for the infrastructure that generated those gains. Both logical and fair. Answering Bloom’s conundrum, the gains created by new infrastructure creates the taxable capacity that can pay for it; the citizenry in general, not speculators, are the beneficiaries. Bloom, the innovator, seizes the possibility of economic wealth creation through the prism of principled opportunism – not dated ideology.

The lessons to be drawn from James Joyce’s insights are not time-limited, but their implementation demands freedom from unnecessary regulatory interference. As already noted, Irish citizens enjoyed a large measure of civil liberty and independent thought that favoured rationality over rules. It was their birthright and was taken completely for granted. It also provided the perfect setting for a free market in business, commerce and trade. But the greatest gifts endowed by natural law, like fresh air, are unseen and unacknowledged – until they are lost. Only then do we wonder why we never noticed them.

When abject, unquestioned compliance is demanded

I have written extensively on the limp submission of our citizenry to the autocratic militarization of lockdown enforcement. In “Economic Consequences of Demented Leadership” I wrote: “It was the UK government’s choice to address [the Covid threat] by slavishly adopting scaremongering measures devised by conflicted “experts” – a choice that put the economy into enforced coma for two years, while other jurisdictions achieved better outcomes by allowing their citizens to evaluate the risks, both to themselves and others, and then make up their own minds on how to behave”. But in this country lockdowns demonstrated how easily the power of fear may be commandeered by the authorities when they require abject and unquestioned compliance. Officialdom and its tiers of willing lackeys were treated to a seminal training-session on the techniques of public mind-control. The lack of vigilance that allowed fear to intrude and take such a powerful hold is itself an attribute of the very freedom it insidiously proceeds to destroy.

Now the same fear-based formula is being applied on the issue of climate change. I stress that I am not addressing the issue of whether there really is a “climate crisis” – only that I’m considering the state’s methods for framing its antidotes – in particular the type of wartime language being deployed. It is difficult to engage in the scientific processes of criticism, disagreement, debate and rigorous interrogation, all the very essence of true education, when we now have a primacy of authority closer to Galileo’s dispute with the Vatican over whether the earth rotates around the sun, rather than observation-based science which, at that time, was embargoed.

Putin is green after all!

It is interesting that “Politico Europe”, a publication steeped in green politics, has wryly named President Putin as a “power player” for having inadvertently advanced Europe’s green agenda. Because of his war against Ukraine, and his ensuing manipulation of energy supplies, clean energy is now at the heart of European security.

Unintended consequences seem to work in many ways: the Covid experience showed the ease with which a society can descend into autocracy; Putin is praised for advancing Europe’s green aspirations; energy availability has been decimated and price rises have been astronomic. China, already tyrannical politically, is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, but also the world’s largest producer of hydroelectricity, solar and wind power – and therefore the world’s largest producer of renewable energy. But China’s industrial needs determine its energy needs – and this determines whether more coal-fired power stations – and coal-mining – are needed.

EU rules guarantee its own demise

Meanwhile the EU continues to frame belief-defying policies that might as well have been designed to wreck what’s left of its deeply indebted economy. Its latest wheeze is a new “carbon border” tax “designed to level the playing field between the EU and the rest of the world, ensuring that environmentally friendly goods made in Europe cannot be undercut by goods made in countries with less stringent green standards.”

So here we have the ultimate encapsulation of protectionist trade policy – and yet another example of the EU’s obsession with tax competition and a “level playing field” – all entirely consistent with its frantic drive toward total economic extinction.

© Emile Woolf January 2023 (website)