Last time on Nostalgia Album we became concerned about Ernestine, my great-aunt by marriage, who at first glance had moved on, relocating to Lancaster, after her husband had been killed in the First War (as had her sister’s husband). Her son John Jr, born in Liverpool where she married John Sr, was to die in the Second War.

The 1921 census shows her still in Liverpool, a widow living with her parents and three-year-old John Jr, in one of the neat back to back terraced houses characterising the tight-knit working and lower-middle-class areas of the Merseyside port. Such places were beginning to worry me too. Another son of the inter-war years, Coronation Street creator Tony Warren said he wanted his scripts to portray the social drama of such tight-knit Northern communities governed by strict rules, none of which were written down.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

A previous episode of Nostalgia Album contained the above photograph of my father with his grandparents. All were immaculately dressed. The pavement is spotless. Different times. Even in my 1960s childhood, doorsteps had to be polished with rud weekly. Clothes washing took place on a Monday. Every curtain in the street had to be opened and closed by a particular time.

The recollection of those strict social expectations began to nag at me, especially upon seeing in our family Bible John Sr had been born only six months after the Christmas Day wedding of my grandparents. John Sr’s marriage to Ernestine and the birth of his son, John Jr, were omitted from the Bible altogether.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

The 1920s and 1930s voter registration lists for Liverpool are available, however, despite the broadening of the franchise after the First War, not everyone was eligible to vote. Ancestry.co.uk explains,

“Property restrictions were finally removed for men in 1918, when most males age 21 and older were allowed to vote. The franchise was extended to some women over age 30 in 1918, but it was not until 1928 that the voting age was made 21 for both men and women.”

Although Ernetine’s father appears on the registry, his wife and daughter don’t as the franchise depended upon property ownership, residency and the rateable value of the property. Looking down the names on Ernestine’s Street suggests the ratable value of the street wasn’t high enough to allow everyone to vote. The only women on the register appear to be women householders or single occupants, therefore excluding Ernestine and her mother.

Universal suffrage as we would understand it today wasn’t introduced until 1928 when all over 21 could vote. However, there is no sign of any of Ernestine’s family on that register and working backwards shows Ernestine’s father disappears from it after 1922.

There is, therefore, a gap in her biography with the index of the government’s wartime residency survey showing Ernestine to be in Lancaster in 1939. However, during the gap, her son John Jr, albeit in his teens, lives in Carlisle (not in Lancaster with his mother or in his native Liverpool) and marries a Carlisle girl. The next port of call must be Ernerstine’s detailed entry in the 1939 residency survey which I was able to read after joining a genealogy website.

Familiar with the North Lancashire city, I recognised her address at once. Lancaster lies on the River Lune just before it reaches Morecambe Bay at the Sunderland point sand flats. It is hilly, tidal (there are neglected Victorian warehouses at the riverfront) and has an urban population just shy of 60,000. Visitors arriving by rail alight at Lancaster Castle station. The actual medieval castle sits on a sharp rise near the railway line and is kept company by its own priory. A working prison until 2011, it provided a secure court for the trial of the IRA’s Birmingham Six in 1976.

Ashton Memorial viewed from Lancaster Castle,

Stephen Gidley – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Beyond is a modestly sized but bustling town centre surrounded by tight-packed streets and mills reminiscent of its distant neighbour beyond Shap and its much larger mill town cousins of East Lancashire.

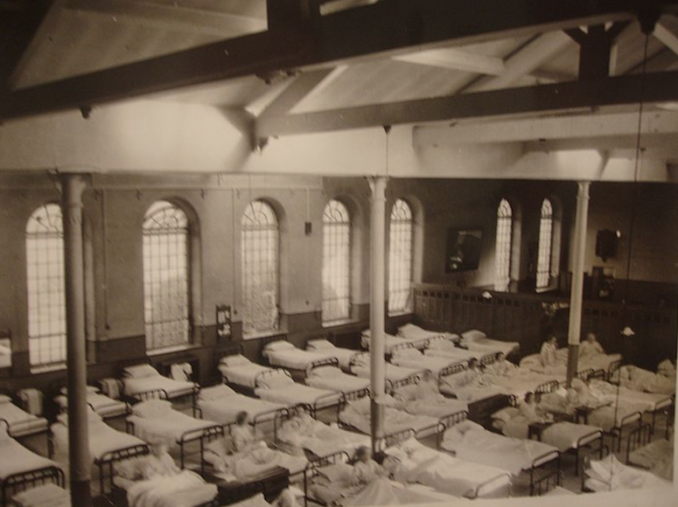

Once home to the largest linoleum factory in the Empire, proprietor James Williamson, the Lord Ashton, miffed at the local alderman’s refusal to allow him to build a memorial to the fallen of the Great War, erected an even bigger ‘folly’ which dominates the town on a hill to the south and announces the city to traffic on the M6. Beyond the memorial, on an outbreak of pleasant pasture rising slowly towards the Trough of Bowland, sits Ernestine’s 1939 residence. As his mother was also resident there, albeit decades later, its grim facade allows for a description from Alan Bennett’s memoir.

“Lancaster Moor hospital is not a welcoming institution. It was built at the beginning of the 19th century as the County Asylum and workhouse, and seen from the M6 it has always looked to me like a gaunt grey penitentiary.”

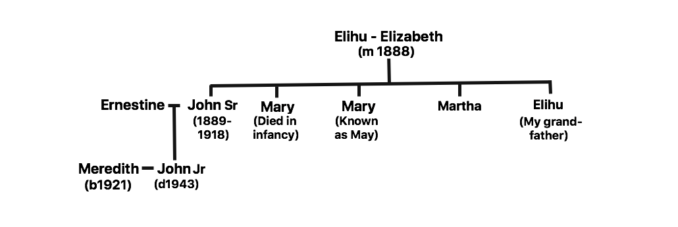

Looking through the 1939 Residency register, I set about counting the patients. Towards the bottom of the 71st page, I began to encounter the staff – of which there were another several pages. With 44 names per page, there were over 3,100 mental patients at Lancaster Moor Hospital in 1939, in the days of hundred-bed dormitories tightly packed with steel-framed beds.

Lancaster Moor dormitory 1948,

University of Liverpool, Faculty of Health – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Later in his memoir, Untold Stories, the Leeds born actor and author describes visiting time,

“… a scene of unmitigated wretchedness. What hit you first was the noise. The hospitals I had been in previously were calm and unhurried; voices were hushed; sickness, during visiting hours at least, went hand in hand with decorum. Not here. Crammed with the wild and distracted, lying or lurching about in all the wanton disarray of a Hogarth print, it was a place of terrible tumult.

Some of the grey-gowned wild-eyed creatures were weeping, others shouting, while one demented wretch shrieked at short and regular intervals like a tropical bird. Almost worse was a big dull-eyed woman who sat bolt upright in her bed, oblivious to the surroundings, as silent and unmoving as a stone deity.”

Ernestine’s husband died of sickness after the war following an injury ominously described by an understated Royal Army Medical Corp doctor as ‘wounds to the head and chest’. We must imagine her nursing and losing a physically and mentally scarred young husband while bearing and caring for their newborn son. Ernestine’s father disappeared from the Liverpool voters register because he died in 1923, aged 62. His wife died the following year, aged 67.

Lancaster Moor Hospital,

Ian Taylor – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

A pre-war Lancashire Evening Post article reported the Lancashire Public Assistance Committee’s concern at the increase in mental illness in the county. An Accrington councillor, Mr Constantine, told the committee,

“This increase is largely due to the stress and strain of life in Lancashire. The conditions in which people, particularly women, have to work at the present time, and insufficient money, are having their toll. The Means Test and unemployment are also having an effect, but the greatest thing is the uncertainty of what is going to happen in the future.”

Widowed and alone with a small son and in dire and uncertain economic times, we must presume life became too much for Ernestine, leading to her incarceration at the Moor Hospital and to her young son being passed to his surviving grandparents in Carlisle. Although Bennet is harsh on the institution, previously others had been more positive. The Lancashire Evening Post of Thursday 5th October 1933 told of an alderman Smith of Nelson reporting to No.6 Burnley Area Guardians Committee,

“Upon a visit of inspection to the county mental hospital, Lancaster … this institution was a good example of what a mental hospital should be.”

A more recent local history piece by Joscelin Woodend entitled The Evolution of the Treatment of the Mentally Ill: How Lancaster County Lunatic Asylum Changed the Face of Treatment gives guarded acknowledgement to progress made there.

“The Lancaster County Lunatic Asylum played a crucial role in the development of the treatment of the mentally ill not just in Lancaster, but throughout Lancashire. … The change that occurred between treatments in the Early Modern era and those used in the Victorian and Modern era developed greatly. Despite its contribution to development, it is still difficult to ignore the negative feelings and memories attached to the Moor Hospital. It carries a stigma of mistreatment, like many other asylums, that is hard to remove.”

Ernestine died in the County Mental Hospital in 1951 aged 61. We must assume she spent half her life there. Her son was killed serving his country in Bône, Algeria, in 1943. Perhaps the news was kept from her or perhaps she was too ill to understand?

***

With the eldest son killed in the First War and his son killed in the Second, the family Bible passed to the eldest daughter, my great-aunt Mary (known as May). She wrote the entries many years in arrears, as I was too for the present generation. Dating mistakes show she filled it in after 1965 and when doing so was referring to family events that occurred up to four decades earlier. So why did she miss out the marriage of John Sr and Ernestine and the birth of their son?

We must return to Alan Bennet’s memoir. Upon admitting their loved one to the hospital, Alan and his father have a chat with a doctor. The doctor asks if the mother had any history of mental illness. Young Alan says of course not while his father stares at his shoes. The doctor asks what the grandparents died of. Alan explains but his father is forced to interrupt. Unbeknown to Alan, his mother had a previous ‘episode’ before he was born and one of his grandparents had committed suicide by throwing himself in the canal.

Such things weren’t spoken of in those days and Aunty May (who ironically was to lose her mind and spend the last years of her life in such an institution) will not have hesitated to omit a fallen brother conceived out of wedlock and his widow who spent decades incarcerated in an asylum.

Different times indeed.

© Always Worth Saying 2022