Breakfast

His place was laid,

The messroom clock struck eight

The sun shone through the window

On his chair.No one commented on his fate,

Save for a headshake here and there;

Only old George who’d seen him die

Spinning against the autumn sky,

Leaned forward and turned down his plate.And as he did, the sunlight fled,

As though the sky he’d loved so

Mourned her dead.Hannah M. Hunt

On the evening of the 17th May 1917, near Douai in Picardy, a German pilot officer on the ground, Lieutenant Hailer, saw a British SE 5A fighter fall from a thunder cloud, spinning and inverted with a dead prop. The engine was leaving a cloud of black smoke, probably caused by oil leaking into the cylinders. The SE5a’s engine had to be inverted for this to happen. The Hispano engine was known to flood its inlet manifold with fuel when upside down and then stop running.

A crowd of Germans hurried to the crash site and found the British pilot dead in the wreckage. Nevertheless, they took the pilot to a field hospital where he was pronounced dead, due to a broken back and a crushed chest, along with fractured limbs. It was noted that the body and the crashed aircraft bore no signs of battle damage. Identification found on the body revealed the pilot to be Acting Captain Albert Ball, the British fighter ace with 44 confirmed victories. It was as though the Royal Flying Corps’ then premier ace, had simply fallen to earth.

Albert Ball was born in Lenton, Nottingham on 14th August 1896. His father, also Albert Ball was a successful businessman who would become the Lord Mayor of Nottingham and later knighted. Young Albert had two siblings, a brother and a sister. Albert’s parents could afford to be indulgent with their elder son and he was brought up to have working knowledge of things mechanical and electrical. And what may seem bizarre and trigger today’s social workers, Albert junior was raised with firearms and became a crack shot. He was also a deeply religious young man.

He studied at Grantham Grammar School, Nottingham High School and transferred to Trent College at 14. He was not particularly academic but showed a love of mechanical things, carpentry, modelling, the violin and photography. He served in the Officers’ Training Corps at college and when he left in 1913 at the age of 17, his father helped him gain employment at the Universal Engineering Works in Nottingham.

When war broke out in 1914, Ball enlisted in the 2/7th (Robin Hood) Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters (Nottingham and Derby Regiment). He was rapidly promoted to Sergeant and commissioned second lieutenant, Gazetted on 29th October 1914. He was assigned to training recruits, a rear echelon role that irked him. He tried to transfer to front-line duties but remained based in England. He managed to find time for a brief engagement to Dot Allbourne, but slightly caddishly, maintained interest in other girls.

Ball hit upon the idea of learning to fly to get to the front any way he could, and started private lessons at Hendon Aerodrome. He would wake at 0300 and motorcycle to Hendon for a pre-dawn flight, before riding back to commence military duties at 0645. He seemed to have an indifference to the accidents and suffering of his fellow student pilots that arguably bordered on psychopathy. He wrote to a friend:

Yesterday a ripping boy had a smash, and when we got up to him he was nearly dead, he had a two-inch piece of wood right through his head and died this morning. If you would like a flight I should be pleased to take you any time you wish.

He was considered to be a less than average pilot by his instructors, but gained his Royal Aero Club Certificate on the 15th October 1915. He was transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and detached to an aerodrome near Norwich. He soloed on a Farman biplane but his landing was rough after having stood guard all night. When his instructor commented sarcastically on the landing, Ball responded angrily, but would continue to have a series of rough landings. He completed training at the Central Flying School Upavon and received his wings on the 22nd January 1916.

Imperial War Museum Photograph Archive Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Second Lieutenant Ball joined 13 Squadron RFC at Marieux in France, on 18th February 1916. He was assigned to flying reconnaissance flights in a BE2c and was shot down by anti-aircraft fire on 27th March. A few days later on a flight, he had a running battle with a German observation aircraft, during which his observer fired an entire drum of Lewis Gun ammunition before they were driven off by a second German aircraft. In letters home to his father, he tried to dissuade his younger brother from following him into the RFC.

I like this job, but nerves do not last long, and you soon want a rest.

Ball’s developing skills and penchant for aggressive action allowed him access to the Squadron’s single-seat fighter, a Bristol Scout. He found the small, agile machine a joy to fly and he lavished praise on the machine in letters home.

He was posted to Number 11 Fighter Squadron RFC on 7th May 1916, a unit that flew Nieuport 16s and FE 2Bb “pushers.” In one of his letters home at this time he complained of fatigue and the lack of hygiene in his assigned billet in the local village. Ball elected to live on the flight line and built a hut for himself, complete with a garden. One can’t help wondering just how popular this made the newcomer with his fellow pilots.

Ball adopted the tactics of a “lone wolf” pilot who stalked his prey from below until close enough to use the upper wing-mounted Lewis Gun angled to fire upwards into the enemy crew, a tactic beloved by German Night Fighters in WW2 against British bombers. He would hold the control column between his knees while he changed the drums of ammunition. He was a “lone wolf” on the ground as well as in the air and because he worked on his own aircraft, he presented a dishevelled and unkempt appearance. He scored his first kill on 16th May 1916, brought down two LGVs on 29th May and a Fokker Eindecker on 1st June whilst flying a Nieuport. He added a balloon to his tarry by destroying an observation balloon with phosphorus bombs on 25th June. On 2nd July he added two more victories and became an ace. As if in premonition, he wrote to his parents asking them “to take it well” if he were killed in action.

He requested time off, but was instead detached to No 8 Squadron where he flew BE2s from 18th July until 14th August. During this time he was tasked with dropping off an agent behind enemy lines. Having dodged three enemy fighters he landed in the field, only to have the agent refuse to get out of the aircraft. During his time with 8 Squadron, he was awarded the Military Cross (MC) for “conspicuous skill and gallantry on many occasions.” On his 20th birthday Ball returned to 11 Squadron and destroyed three Roland CIIs during one sortie on 22nd August 1916. He ended that day taking on fourteen German aircraft and struggled back, short of fuel to the Allied lines. He was transferred to 60 Squadron RFC on 23rd August and his new Squadron Commander gave him carte blanche to fly solo missions, plus his own aircraft and ground crew. He had the Nieuport’s propeller boss painted signal red and by the end of the month had increased his kills to 17 enemy aircraft, with three downed on the 28th August.

Ball went on leave to England where his feats had received much publicity. It had been British policy to not publicise RFC successes, but the carnage of the Battle of the Somme made all successes something to propagandise. The young pilot much enjoyed the attention, particularly that of the ladies.

He returned to France and scored two more kills on 15th September. He scored three triple daily victories and by the end of the month had amassed a score of 31. Making him Britain’s top fighter ace. His superiors ordered him to rest as he was taking unnecessary risks and arranged a Home Establishment posting in England. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and Bar “for conspicuous gallantry and skill” and the Russian Order of St George in the same month. Back in England he was lauded as a national hero and was invested with the MC and DSO and Bar by King George V. He was promoted to substantive Lieutenant on 8th December 1916.

Lieutenant Albert Ball was posted on instructional duties to Orford Ness in Suffolk. He was invited to test fly the new SE5a fighter in November, but he was unimpressed with the new aircraft. He found it to be heavy and too stable, compared with the nimble Nieuport. His views contrasted markedly with those of fellow pilots who had flown the aircraft. Perhaps they were looking at it as a type, which would give more inexperienced pilots a fighting chance against the superior German fighters. During this time, Ball met 18-year-old Flora Young and they became engaged on 5th April 1917. It was while serving on the home front that he was able to lobby for the building and testing of the Austin-Ball A.F.B.1 fighter, which he had designed and helped to develop. He hoped to be able to take an example of the type to France with him, but the prototype was not completed until after his death in action.

Ball chafed at instructional duties and wrangled a posting back to France as a flight commander with newly- formed 56 Squadron RFC. It was to be equipped with the SE5a and Ball was unhappy, insisting that his aircraft should have modified gun mountings to fire upwards and downwards instead of the two Vickers Guns synchronised to fire through the propeller. He flew the SE5a when on patrol with the rest of the Squadron, and used a Nieuport for his “lone wolf” sorties. During this time he continued to score a steady rate of kills, despite having constant problems of his guns jamming in the SE5a. He reverted to the Nieuport and scored his 44th kill on 6th May, an Albatros DIII. He continued to fly lone patrols, but the German fighter pilots were getting much better as were their tactics and he was increasingly returning with more comprehensive battle damage. On his final letter home, Ball wrote:

I do get tired of always living to kill, and am really beginning to feel like a murderer. Shall be so pleased when I have finished.

Arnold, Norman G, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On the 7th May 1917 Albert Ball was leading a patrol of eleven aircraft in his SE5a, when the patrol encountered a large number of German fighters from Jasta 11. The two sides engaged in a confused, running dogfight in decreasing visibility and the two formations became scattered. Albert Ball was last seen in pursuit of a red Albatros DIII, the mount of Lothar von Richthofen, the Red Baron’s younger brother, until the Germans went to the crashed SE5a that had fallen from the thundercloud.

The Germans credited Lothar von Richthofen with shooting down Ball, but he disputed this as he claimed that he shot down a Sopwith Triplane and not an SE5a. It is probable that the younger Richthofen was caught up in the propaganda game, spun by the German High Command. It is more likely that Albert Ball became disorientated in the storm cloud and suffered vertigo, inverting the aircraft and cutting out the engine. The fact there was no battle damage on the crashed SE5 supports this hypothesis.

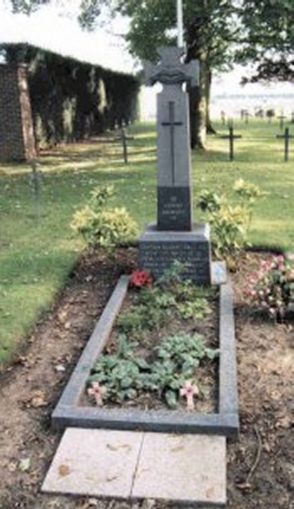

At the end of the month that the Germans dropped messages behind Allied lines announcing that Ball was dead, and had been buried in Annoeullin with full military honours, two days after he crashed. Over the grave of the man they dubbed “the English Richthofen”, the Germans erected a cross bearing the inscription In Luftkampf gefallen für sein Vaterland Engl. Flieger Hauptmann Albert Ball, Royal Flying Corps (“Fallen in air combat for his fatherland English pilot Captain Albert Ball.” The tragedy is, there was a certain inevitability about the death of Albert Ball. Notwithstanding the terrible attrition rates of RFC aircrew, Ball was driven and took too many risks. He was a loner and died a loner’s death, disorientated in a dead aircraft spinning to earth.

Citation for Posthumous Victoria Cross:

Lt. (temp. Capt.) Albert Ball, D.S.O., M.C., late Notts. and Derby. R., and R.F.C.

For most conspicuous and consistent bravery from the 25th of April to the 6th of May, 1917, during which period Capt. Ball took part in twenty-six combats in the air and destroyed eleven hostile aeroplanes, drove down two out of control, and forced several others to land.

In these combats Capt. Ball, flying alone, on one occasion fought six hostile machines, twice he fought five and once four. When leading two other British aeroplanes he attacked an enemy formation of eight. On each of these occasions he brought down at least one enemy.

Several times his aeroplane was badly damaged, once so seriously that but for the most delicate handling his machine would have collapsed, as nearly all the control wires had been shot away. On returning with a damaged machine he had always to be restrained from immediately going out on another.

In all, Capt. Ball has destroyed forty-three German aeroplanes and one balloon, and has always displayed most exceptional courage, determination and skill.

The original uploader was Peter Warrington at English Wikipedia., CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

© Blown Periphery 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player