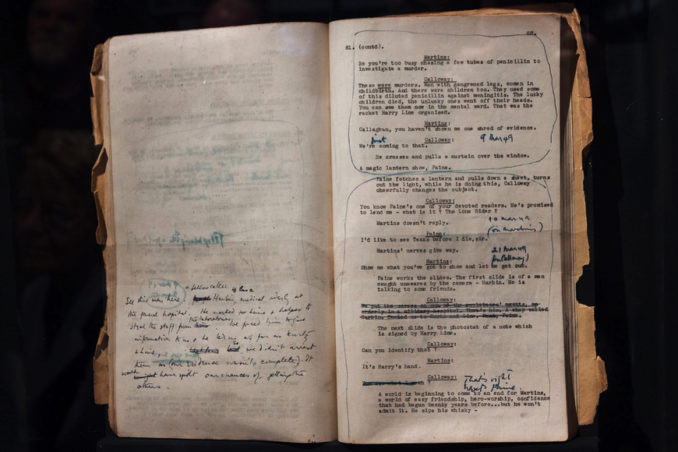

Vienna-The-Third-Man-Original-Director’s-Script,

Mr Snooks – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The Third Man is a wonderfully evocative, innovative, and fascinating film, directed by Carol Reed with the screenplay by Graham Greene, set in the dystopian ruins and chaos of immediate post-WW2 Vienna, which at that time was divided up amongst the Allies into zones/sectors of administration. Pulp Western writer Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) arrives to meet up with his old friend Harry Lime, (Orson Welles) only to find that he’s dead, killed in a street accident — or is he? The investigating officer, Calloway (Trevor Howard at his bluffest “British Major” best) informs Martins about Lime’s unsavoury character, but his grief-stricken lover, Anna (Alida Valli – here enigmatically channelling both Garbo & Bergman) doesn’t believe the stories, so perhaps neither should Martins. Deciding to investigate Lime’s death, Martins remains in Vienna to find an elusive third man who may have witnessed Lime’s accident. As the supremely naïve Martins, a monoglot stranger in a strange land, descends through the successive levels of deception, he discovers the extent of his friend’s corruption, & the moral choices loom. (Warning – some spoilers ahead)

The Third man (1949),

Insomnia Cured Here – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The Third Man (1949),

Insomnia Cured Here – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

TTM is basically a perfect film noir. It features a convoluted plot rooted in the banality of evil that (unlike The Big Sleep) never loses its own thread, and deeply flawed characters that draw the viewer in rather than disgust. And those are just the basics of its storytelling: the cinematography and music are now legendary in their influence on contemporary filmmaking. It’s is one of the handful of motion pictures (Rashomon, Casablanca, The Searchers) that have become archetypes — not merely a film that would go on to influence myriad others but a construct that would lodge itself deep in the unconscious of an enormous number of people, including people who’ve never even seen the picture. The first time you see it, your experience is dotted with tiny shocks of recognition — lines and scenes and moments whose echoes have already made their way to you from intermediary sources.

If you have already seen it, even a dozen or more times, (guilty, m’lud) the experience is like hearing a favourite piece of music — you can, as it were, sing along. For example, consider where else you’ve heard music quite like the entire film score of TTM. Did you guess Brazil? That’s no accident. Both films feature thoughtful protagonists lost in nightmarish cities where the law seems absurd and almost no one is trustworthy or reliable. The cheerful music provides an ironic background to the heinous acts depicted on the screen. (And in case the thematic similarities aren’t enough to convince you of the cinematic lineage between these two, Terry Gilliam’s co-writer on Brazil, Charles McKeown, plays a minor character called “Harvey Lime.”)

Similarly, the visual language of TTM has entered our cinematic lexicon. First, notice the deep, silken blacks. It must be watched with the lights off, or you’ll lose the subtle gradations of shadow to ambient glare. Second, notice the deliberately off-kilter angles that Reed uses to frame his shots. By keeping long portions of the film off-centred, he keeps the viewer off balance and communicates the confusion and anxiety that the protagonists experience whilst in Vienna. Third, notice how slowly the storyline unfolds. For instance the scene where each character is waiting on pins and needles for the villain to arrive, but instead an old drunkard selling balloons shows up. It’s the world’s longest cat-on-a-dustbin gag, but it’s also almost unbearably tense.

So what makes “TTM” so remarkable? First of all, it has first-class acting. Even though Orson Welles is on screen for only about ten minutes, he leaves an indelible impression. He also wrote the now-famous line about the Swiss cuckoo clocks. Cotten and Valli play their parts outstandingly. Director Reed took full advantage of the decrepit condition of post-World War II Vienna and spent six weeks filming there. The city had been bombed relentlessly. The shattered buildings, piles of rubble and their evocative shadows form a haunting backdrop to the outdoor scenes, particularly at night. Vienna’s division into four occupation zones (US, Soviet Union, United Kingdom and France) with four distinct armies, also adds to the chaos that was Vienna.

Other scenes, such as those on the Ferris wheel, in the central cemetery and the rat-filled sewers each have a built-in drama of their own. Graham Greene’s screenplay is superb, where his genius for dialogue and suspense shines through. His glimmer of an idea, written on the back of an envelope, became the plotline of “The Third Man”. He actually wrote a novella version of “The Third Man” at the same time he wrote the script. (In fact, Greene wrote both versions at the Sacher Hotel, where Martins stays in the film). Robert Krasker’s quirky cinematography was avant-garde in 1949 and most of it holds up well. For example, he evoked the Austrian food shortages with fleeting shots of hungry and desperate men. His expressionist use of light and shadow help make the film suspenseful. His oblique camera angles and harsh lighting seem a bit clichéd now, but are nevertheless effective in capturing the mood of Martins’ disturbing and disquieting time in Vienna. Finally, there’s the zither music. Whilst out for an evening, director Reed and some cast members heard Anton Karas, a 40-year-old local musician, play the zither for tips. Immediately struck by the melancholy sound, Karas was signed to compose and perform the soundtrack for the picture. The “Third Man Theme” subsequently became an international hit.

The Third Man (1949),

Insomnia Cured Here – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Naturally, we turn now to the villain who takes so long to arrive: the third man, Harry Lime, played unforgettably by Orson Welles. This was another collaboration between Cotten and Welles following Citizen Kane, and to some extent they play grittier, more human versions of their characters in that film. As Holly Martin, Cotten is the friend who wants desperately to believe in Harry Lime. But over the course of the film, Martin must confront once and for all Lime’s selfishness, duplicity and appalling lack of a moral compass. Because as we discover, Lime is not only a smuggler and racketeer, but one who has been selling diluted antibiotics to the families of children with spinal meningitis. Small children have died in horrific agony because Lime wanted to make a quick buck. He had no other reason for conducting this scheme — just simple, common avarice and an utter disregard for human welfare. It’s a small act with wide-ranging consequences, and Cotten’s expression as he looks at the twisted bodies of dying kids makes the film’s (and Lime’s) ending inevitable.

How did Graham Greene arrive at this unusual and moving story? Settle down Puffins for some background information, interwoven with fascinating and bizarre threads. In April 1946, in the bleak aftermath of the second world war, American and British intelligence services arrested seven men and three women in Berlin on charges of manufacture, possession, and sale of fake penicillin. A former German army private was the alleged chief of the fake drug ring that included,

“Two former GIs in love with frauleins and an American doctor with a passion for fine cameras…who got at least $13,000 [about $170,000 (£120,000) today] in cash from one Berlin druggist for penicillin.” The fake penicillin was apparently prepared in two forms: vials of glucose liquid and stolen used penicillin bottles filled with crushed mepacrine (antimalarial tablets), and face powder. Although we can find no clinical trials of intravenous face powder, it seems doubtful that it is beneficial, and mepacrine is unlikely to be effective against bacteria, the resulting powder for reconstitution for injection is also likely to have been dangerously contaminated with environmental pathogens. A Russian officer given an injection of the fake penicillin was described as being in a “critical condition.”

The criminal network was uncovered when a drunken gang member dropped a penicillin bottle in a bar. Penicillin was scarce but much sought after as an innovative cure of bacterial infections, and had become a currency in post-war Europe. The Times reported from Berlin,

“There is great illicit demand for penicillin here for the treatment of venereal diseases. Supplies are strictly controlled by the British and American authorities, being reserved for the treatment of their soldiers, and secondarily for the treatment of German women likely to spread disease. Otherwise supplies are not available.”

There is also evidence of an illegal penicillin trade in post-war Vienna. Zane Grey Todd was head of criminal investigation in the American sector. His obituary tells us that,

“His most dangerous case involved two American medical officers who were stealing and selling penicillin on the black market, aided by a former Miss Austria, with whom they were living.”

That Todd may have been a key source for Greene is suggested by a tributary clue in the film — Martins gives a cultural talk on the American author Zane Grey. Another source was Peter Smollett, ostensibly The Times correspondent in Vienna, who apparently told Greene about “a children’s hospital and diluted antibiotics.” Smollett was a Soviet double agent born in Vienna as Hans Smolka, and a scene in the film takes place in a fictional Viennese Bar Smolka. During wartime, Greene had worked for SIS under Kim Philby, one of the “Cambridge five” Soviet double agents, who recruited Smollett.

Alexander Korda, the executive producer of The Third Man, was also a British spy in the US. Greene carefully blended these multiple murky strands of spying into fiction. Although Greene credited Charles Beauclerk, a British intelligence officer in Vienna, as a source, he may have used Beauclerk as a smokescreen to protect Smollett and perhaps even Philby. Penicillin was so coveted that it was used as an espionage tool at the start of the Cold War. In post-war Vienna a US intelligence officer, Major Peter Chambers encouraged Russian soldiers to share Red Army secrets and defect, in return for penicillin to treat their gonorrhoea and syphilis………..

Whilst most film noir are about betrayal, The Third Man is one of the few that lays that betrayal at the feet of an old and dear friend and not a woman. Stories about conniving femme fatales, like Double Indemnity or The Postman Always Rings Twice, are easy to tell and preach at men to stay away from strong women (who will go to the same lengths as men) and stop at nothing to get what they want. But TTM gets at the unspoken core of male friendship and pries the lid off the dishonesty that occurs when one person is carefully, tactically blind to the flaws of another. It’s no surprise when we learn that Lime has always been a sucking parasite of a friend. What does surprise us is Martin’s willingness to finally admit it.

The Third Man (1949),

Insomnia Cured Here – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Holly Martin isn’t the only one who’s been blind to Lime’s flaws. Lime’s girlfriend, Anna, knows exactly what he’s been up to, but refuses to internalize the implications or consequences of his behaviour. She loves him, purely and at her own expense and to her detriment, even choosing to remain in Vienna where the Russian authorities are looking to put her in prison rather than leave Lime behind. It’s disgusting and tragic, but also deeply human and true. When Anna leaves Martin behind at the end of the film, she’s doing her best to remain faithful — even if her loyalty means her destruction.

This ending articulates one of the key values in any noir film or story: no good deed goes unpunished. Martin chooses wisely, but doesn’t win the girl. The Allies won the war, but Vienna is still a den of iniquity. And in fact, it’s that win which allowed a villain like Lime to arise. Without the absurdly complicated division of Vienna into Allied “zones” following the war, Lime would have no market for his misdeeds. If goods could flow easily throughout the city, he wouldn’t get a high price for smuggled drugs. The system, despite being created by well-meaning people, created the opportunity for this man to thoughtlessly and indirectly murder scores of children. Lime himself (with writing assistance from Orson Welles) explains this rather beautifully – possibly the best 3 minutes in cinema history:

“In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

An instant classic and international hit, “The Third Man” won the (then) prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival (1949), the British Film Academy’s best British film award (1950) and an Academy Award for Robert Krasker’s cinematography (1951). The British Film Institute selected “The Third Man” as the best British film of the 20th century (1999). It was also named as The Greatest Foreign Film of All Time (in Japan), & is warmly recommended to the Puffins assembled.

© 2021 DJM

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player