Portrait of Frankie Howerd in London,

Allan Warren – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Nothing spoils a joke more than having to explain it. There are six rules of humour. No there aren’t, there are eleven types of comedy. That’s not true, there are nine ways to make people laugh. Whatever. What we can say with certainty, is that any taxonomy of laughter should include ‘innuendo’. Although I’m not an expert on grammar (I never could grasp a dangling modifier), I can use the dictionary. According to the Oxford English, innuendo is “an allusive or oblique remark or hint, typically a suggestive or disparaging one.” It has a root in two Latin words, ‘in’, which means ‘towards’ and ‘nuere’ which means, ‘nudge, nudge, wink, wink, say no more!’. It should but it doesn’t. Not quite. ‘Nuere’ means ‘to nod’. Therefore innuendo’s literal meaning is ‘to nod towards’.

The word emerges in the mid 16th century as an adverb of explanation in legal documents meaning ‘that is to say’. In the modern-day, the romantic languages of the continent would use variations of ‘insinuare’ instead. In English, this means to suggest or hint (insinuate). The Latin root is ‘sinuare’ which means ‘to curve’. A bit more sophisticated than a nod, as the Continental can be a bit more sophisticated than the more direct Anglo-Saxon. The Germans use a different word altogether, ‘Anspielung’, which means, “a completely humourless race of people drawing unfunny cartoons about being forced to cut the grass, every Sunday afternoon after kirken, with a push-along mower.”

Those dry Puritan people of the United States often use innuendo to mean a reputationally negative suggestion, free of sexual double meaning. For instance ‘an innuendo surrounds Mr Biden’s IQ’. In English humour, our use of innuendo would be what the Americans would call ‘sexual innuendo’. Below the line, you will often see unread comments that contain but two words followed by an exclamation mark, ‘Sexual innuendo!’ Or rather, for some reason, you don’t. Explanation to come (oo-err).

Having defined sexual innuendo, why does it make us laugh? In these strange politically correct times, does it make us laugh? In fact, why do we laugh at all? In his Forbes Magazine article, ‘The Science of What Makes us Laugh’, Neuropsychologist Fabian van den Berg informs us that other creatures laugh during play behaviour, the assumption being that laughter conveys some social information. Human social behaviour is much more complex than that of animals. It follows, so is our laughter. Van den Berg goes on to say,

“When scanning [the brain], we notice that it has to do with expectations and the violation of scripts. We find things funny that don’t fit with what we think should happen.”

Our brains are good at predicting events, anything that deviates from a routine will ‘pop out’. If an unexpected outcome is non-threatening, we respond with laughter. Therefore, humour is highly social and based upon expectation and the contradiction of expectation. Van den Berg concludes,

“The entire process: the hows and whys aren’t known yet, but I believe the general consensus is that it relays social information to others. It signals that nothing bad is going on, everything is fine, so join in and don’t worry.”

How can expected and unexpected outcomes be categorised? In the completely humourless Huffington Post, Emily Blatchford, (in her article, ‘There Are Nine Different Types Of Humour. Which One Are You?’) lists:

- Self-deprecating

- Physical

- Improvisational

- Wit-wordplay

- Topical

- Observational

- Bodily

- Dark

You’ll note that there are only eight items in Emily’s list of nine. Is that an hilariously unexpected outcome? Is Emily being very clever? Or is she just thick and can’t count? Wikipedia tries a bit harder giving us:

- Repetition

- Hyperbole or overstatement (eg Dawn Butler, would)

- Understatement

- Pun

- Juxtaposition

- Mistaken Identity (Dawn Butler, would)

- Taboo (Dawn Butler…..)

- Comic timing (Daaaaaaawn But-ler),

- Slap(Dawn Bulter with a)stick

- Stereotype

The eleventh is a nod to the bellow the line Puffin community, who are awarded their very own:

- Double Entendre

Double entendre being defined as:

“a spoken phrase that can be understood in either of two ways. The first, literal meaning is an innocent one, while the second, figurative meaning is often ironic or risqué and requires the audience to have some additional knowledge to understand the joke.”

Now we know why unread commentators shout “Double entendre!” below the line. But they don’t. Further research is required.

The Greek Theatre Taormina,

Solomonn Levi – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

As every Puffin knows, our understanding of classical Greek Old Comedy derives from the eleven surviving plays of Aristophanes, who lived between 446 and 386 BC, a mere two and a half thousand years ago. His double entendre and innuendo are used as a political attack, thinly disguised as buffoonery, upon the then powers that be.

In the Aristophanes play, Peace, war has ended and two sisters have been released from heaven to return to live with the mortals. Their names are Theoria and Opora. As well as being a girl’s name, Theoria also means ‘something to look at’ or ‘to see explained’. In modern-day English we still use words derived from it, such as ‘theatre’ and ‘theory’. To the ancient Greeks Theoria would have meant theatre, spectacle and the times at which those things happened, for instance ‘festival’ or ‘holiday’. Then and now, we can have a lot of fun with a girl called ‘Holiday’. If you are thinking that everybody likes to be on Holiday, everybody’s been on Holiday and everybody’s looking forward to going on Holiday, then Aristophanes thought of it before you and put it into his routine. Theoria’s sister Opora’s name can also mean ‘harvest’ or ‘ready to harvest’ or ‘juicy’ or ‘ripe’. Fun can be had there too.

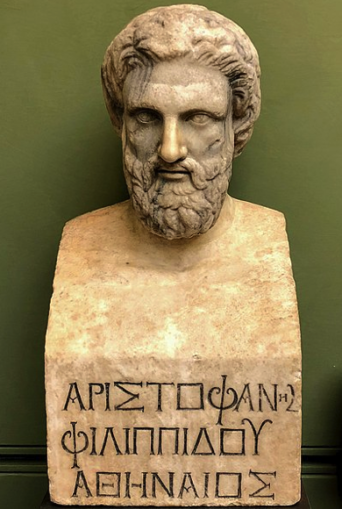

Bust of Aristophanes in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.,

Alexander Mayatsky – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

Although much of Aristophanes’ script is based on clever wordplay and variations on the meaning of the sisters names, some of it is a bit more direct.

TRYGAEUS: “No, for she would touch neither bread nor cake; she is used to licking ambrosia at the table of the gods.”

SERVANT: “Well, we can give her something to lick down here too.”

Filth! Kenneth Williams would be proud. Likewise, *Frankie Howerd Voice*, as Theoria hurries from the bath to the kitchen.

“The girl has quitted the bath; she is charming from head to foot, belly and buttocks too; the cake is baked and they are kneading the sesame-biscuit; nothing is lacking but the bridegroom’s tool.”

Upon Theoria’s arrival in the kitchen naked, and politicians (then as now) being assumed to be corrupt and venal, the staff comment on the stove, or do they?

SERVANT God, what a beautiful one! It’s black with smoke because the Senate used to do its cooking there before the war.

Geddit? Sniggers. Matron! Ding-dong. Oh-behave. I’m free! As Theoria also means ‘games’ the double entendres can be laid on thick and fast by referencing her to different sports.

TRYGAEUS: Now that you have found Theoria again, you can start the most charming games from to-morrow, wrestling with her on the ground, on all fours, or you can lay her on her side, or stand before her with bent knees, or, well rubbed with oil, you can boldly enter the lists, as in the Pancratium, belabouring your foe with blows from your fist or something else. The next day you will celebrate equestrian games, in which the riders will ride side by side, or else the chariot teams, thrown one on top of another, panting and whinnying, will roll and knock against each other on the ground, while other rivals, thrown out of their seats, will fall before reaching the goal, utterly exhausted by their efforts.

So why, below the line, do we shout ‘filth!’ instead of ‘ὀπώρα’, ‘θεορία’, ‘double entendre’ or ‘sexual innuendo’? Because ‘filth’ is such a good word. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as being, ‘disgusting dirt’. Further investigation reveals that the word, in keeping with the elevated literary skills of the Puffin, means a bit more than that. Although we use the word to mean ‘dirt’, it’s origin is the Old English, ‘fylth’, from the Germanic. This means more than dirt, it means ‘rotting matter, rottenness, corruption, obscenity’. It is related to the Dutch word ‘vuilte’ and hence the Afrikaans word, ‘vuil’. But, passing into Old English, the ‘fylth’ in question defines the detritus left behind the as the body rots. In Latin, the connection between the body and its decomposed fate is more linguistically clear, ‘corpus’ (the body) becomes ‘corrumpere’ (‘is destroyed’ or literally, ‘altogether broken’), words that can be applied to morals as well as flesh. These Latin words survive in English today as ‘corporal’ and ‘corruption’.

Kenneth Williams,

Ruby Goes – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Our word ‘filth’ becomes the corrupted division between the corporal and the spiritual. The rotted flesh that remains behind in the fallen world, after the eternal soul has returned to God, as if the intended pure meaning of the writer and a more (literally) earthy interpretation of a reader with that ‘extra piece of (worldly) knowledge’.

Generally, Puffins are not commenting at an obvious double entendre, they are laughing at a realisation that it could be a double entendre, not meant. In doing so they are invoking, amongst other things; wordplay, puns, overstatement and even taboo, an awful lot of what triggers those expected and unexpected scripts that force us to laugh. In keeping with that spirit of wordplay, when a GP author offers to bash one out if given a subject, you know what he will be obliged to research when the Puffins below the line respond, ‘filth!’.

© Always Worth Saying 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player