An even greater slab of armour plate than the one we had stumbled across decades before, stood upright blankly showing its wounds, punched through and scored by shot, rusty red, the memorial to those Finns who lost their lives among these vistas of trees and lakes, of whom more than 700 have no known graves.

The Spanish Civil War just preceded the war in the north. It too came to be seen as an opening act in a wider European conflict, a theatre for the entr’acte where understudies, surrogates could rehearse scripts written in Berlin, Moscow or Rome. But nothing like what was to come, nothing. Spain either from its un-European culture – not just trailing behind but on a different path in all but a few cities of the coast, – Spain was exciting! It was vivid, sharp, exotic, at once violent and indolent, mingling blood and passion. It was everything Finland and north was not. Heat and death seem to grab the imagination of a swarm of young outsiders, artists as much as workers, that arrived to fight battles, mostly uninvited and ignorant beyond a slogan. No wonder the books, memoirs of the Anglos piled up, the combinations intoxicated these first of our 20th centuries tourist soldiers; it wrote itself on the page. None went to Finland for the opportunities to create.

Perhaps that is it; the Winter War (1939-40) and it’s deadlier follow up for the Finns lacked glamour, that adoring context. That and the cause was too ‘problematic’ for the few western intellectuals still swarming around Republican Spanish victimhood – the engagé. True, a small democracy, a country like Czechoslovakia, across the Baltic was being bullied by a powerful neighbour. But the powerful neighbour had won hearts and minds in the big cities, small circulation journals and ‘workers press’, common rooms and debating societies. It, not Finland, was ‘vulnerable’ according to precise Marxist doctrine:

Today the potential danger of imperialist intervention against the Soviet Union is greater than at any other time since 1921. This is the logical outcome of Stalin’s fundamental error of attempting to build “Socialism in a single country,” at the expense of the Revolution abroad. We regret the Soviet’s attack upon Finland and we must hold Stalin responsible for this major blow to the prestige of international Socialism. Nevertheless, it is necessary for the British working class to be on guard against being dragged by their capitalists into a war against the Russian workers and peasants under the hypocritical guise of defending “poor little Finland.” – George Padmore (My emphasis – Larkers A.D.)

Whatever it takes.

George Padmore, born in Trinidad, became a Communist in the U.S. and went to live in the Soviet Union in 1929, from where he preached the doctrine of ‘Pan-Africanism’ and anti-colonialism. When Stalin produced another straight faced shift in his foreign policy seeking now to disarm the suspicions of Great Britain and France, old colonial powers indeed – or possibly to soften up the Germans, the better to make a Pact? – Padmore felt betrayed. Soon he came to London as all England’s bitter enemies do, to find shelter and ways to finance his plans. Such was the deck chair re-arranging going on across the globe at that time, ‘a low dishonest decade’ as ‘Bomb Dodger’ and fellow traveller Auden put it. [Strangely, Auden and Louis MacNeice had been to Iceland and wrote about this trip as of a modern day Saga, but it didn’t produce anything relevant to the Finnish cause.]

‘Hands off Finland’ became the catch phrase of a not very subtle policy of throwing Finland to the wolves by the British Communists and their acolytes, of whom there were now many. By this Finland ought to have done what was a shocking thing when applied to Czechoslovakia – concede to the territorial demands of power politics and like it. The Party demanded nothing less.

Finland had been a Duchy of Imperial Russia until 1917 and the Russian Revolution when the Finns assumed their Independence. A bitter civil war followed – are there any other kind? – between Whites and Reds, nationalists and socialists. This conflict was ended by German troops but it lingered for long afterwards in Finnish life as all such wars do.

In 1939 Stalin gave Finland an Ultimatum at the beginning of his war as ally and best friend to the German Corporal. He had also just completed his purge of the Red Army and Navy. He told his incompetent and presumably suitably terrified of him Red Army commanders he expected a short war and complete victory. What took place was an epic of heroic resistance and superb use of the terrain and climate. The Russian columns laboriously slicing through the centre of the country were ambushed, pinned and surrounded by a nimble adversary. Despite this and all but abandoned for their reliance on the Nazis as their only material supporters of note, Finland signed an Armistice of what is called ‘The Winter War 1939-40’.

But the real war was to come. When Hitler opened his operation against his erstwhile ally Stalin in July 1941 Finnish detachments formed a part of the armies sent to first isolate and then take Leningrad. That is another story beyond the scope of this memoir.

Knocked out of the war finally, the terms of the peace that gave away chunks of the country on the Baltic and in the far north access to the White Sea, Petsamo and to the south the whole of Karelia, creating mass refugees. This also marked the end of the free ranging ancient Sami culture, but not its marginalised existence. The Finns were required to expel the German forces that had been fighting alongside. A bitter task for all concerned. By a miracle and much sacrifice, the Finns had fought the Soviets to a standstill by August-September 1944 – for now. Both sides needed to end the fighting.

Finland was led through these events by a remarkable figure, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1867-1951), Russian soldier, explorer and spy, then Regent of an Independent Finland, Commander-in-Chief and finally, briefly, reluctantly, President. Despite operating against the Allies on the side of Hitler, even meeting Hitler twice, Mannerheim’s motives have largely been treated sympathetically. He was indeed between the Devil and the deep blue sea. Finland suffered for its efforts to hold on to what it had, though never so much as others. It somehow was never quite behind the Iron Curtain but intimately involved in ways that are still hidden behind rumours and Cold War misinformation. It provides in hindsight an example of a particularly adroit Scandinavian form of pragmatism. It may be required again.

Another factor that occurs to this writer is that Finland serves as a useful distraction from examining the wartime record of the Baltic and Nordic countries in its neighbourhood. But independent Finland survived and for that the Finns were quietly thankful. The war was over; the Cold War that placed the Finns on the doorstep of their Soviet mega power neighbour’s war machine, living a life in suspended animation for decades, history prorogued, silent, whose own striking Modernist response to defeat was built over the ashes of wooden cities fire bombed and populations re-located from ancestral lands bounded by minefields and watch towers; a wary neighbour swift to see and mark any slight shift of Finnish behaviour, remembering for both their countries.

Norway too has its scars. The term Quisling enters our lexicon. In the north the silence was not so much for fear of offending the Soviet neighbour – there was great care to be taken of course – but because of its compromised and shameful aspects. Here too, along this strangely unbeautiful shoreline the creations of the Todt organization that could not be taken away remained for long ignored. Only after the collapse of the Soviet Union was there recognition that this or that emplacement, hunks of cracked concrete and worse, ‘trenches’ cut from hard brittle rock were completed by Russian P.O.W.’s worked to death.

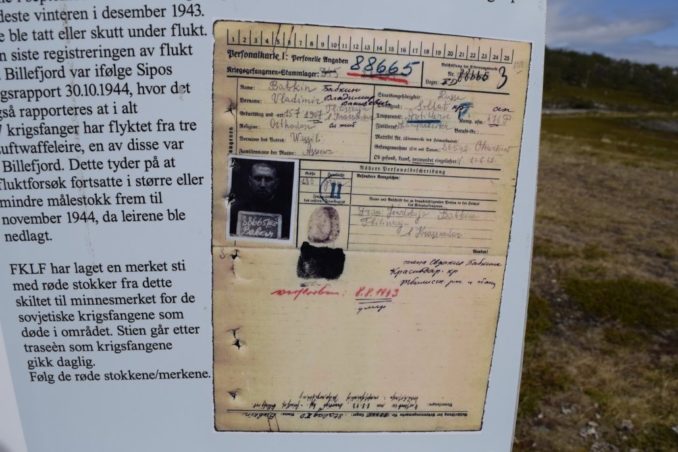

Sites such as these were formerly abandoned and unexplained. Nowadays they have new information boards. (See below)

The conditions under which these prisoner’s worked are difficult to imagine. It snows here in June and between October and March, there is no daylight.

Brand new and painted a rather gaudy red. Russia is, confusingly for this Brit, just out of sight opposite (right) and to the south. Locals told me that there is an now a ceremony held here annually with Russian guests at which speeches are made and lots of vodka drunk.

The countryside – all but tundra and vast forests and massive lakes with unpronounceable names – is to me superb but not everyone’s taste. In the early endless daylight Summer – here June – it frequently becomes very hot. An old companion who has travelled there more times than myself met two oil workers from Libya one time who thought that going north would make a nice change and hit Lapland in a heat wave – 100 F plus in old money. There is also a Mosquito hatch like no other I wish to experience. Net veils and gloves are essential. Even so the view in front of ones face is blurred dark grey by a haze of insects and I have been bitten through my clothing. You don’t want to be there in those weeks.

In 1940-45, this would have been considered a very good road. Today most roads have been tarmacked. As bad as these roads can be in the wet, I somehow miss them now.

The Sami people have had their culture restored – language and customs and costumes respected and their own radio station. But they cannot wander as they did once following their reindeer herds wherever they roamed. Now they live in large modern insulated houses scattered among the trees, snow mobiles and four by fours parked outside.

The people are friendly and polite; it’s not uncommon to meet assistants in shops hundreds of miles north of the Arctic Circle who speak perfect English. I know less about the cities but those who have shared stories speak about the civilised and stylish experience with pleasure.

Lapland has changed since I first visited. What once was frontier and wild is now much, much, less so. It’s always the case as one gets older. Nothing remains the same. Everyone wants better, so old and picturesque cabins have been replaced and the grit roads tarmacked, the horizon punctured by mobile telephone masts of great height. (Nokia was once a timber company.) But If I walk away from the now busy road to the Norwegian border along some sandy track through the stunted Scots pines and feel the breeze off a recently iced covered lake on my face – I’m back.

Coda.

In December 1972 Scottish judge David Colville Anderson was charged and subsequently found guilty of attempting to solicit two under age girls to perform a perverse act upon him. There was certain evidence that placed doubt on the identification of the man the girls described in their complaint. This episode ruined his career. Anderson always denied the charges unto his death.

In his defence Anderson revealed that he had been sent on secret mission to Finnmark behind the Russians back to persuade the German forces holding a well fortified northern Norway to surrender to the British, which they did. Soviet forces in the far north had seized Kirkenes in Norway, on the south eastern shore of the very wide Varanger Fiord – still a sensitive border point – and poised to reach further. A Soviet occupation of the north of Norway was something of a threat even before the smoke of Hitler’s funeral fire had cleared. Anderson suggested on appeal the K.G.B. knew about his role in this successful plot and wanted revenge. This seems unlike the K.G.B. to me. They might have found a kinky Scottish judge with excellent social and political connections of more use blackmailed than disgraced.

Currently N.A.T.O. are increasingly anxious about this northern flank. The thaw is over.

© text & images Larkers A.D. 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player