Public Domain

Today A Bear’s Diary is published as a hardback. It has been available as an ebook for a couple of months. It’s a shortish novel at 65,000 words, decorated with old engravings which give it a spurious air of historical authenticity. If it has a genre it is a historical romance, but the fact that the narrator is a bear confuses things.

I never meant to write a novel. Originally I had planned a two-parter for Going Postal, based on a true story. In 1805 the young Lord Byron went up to Cambridge as an undergraduate and was dismayed to find that he wasn’t allowed to keep his beloved dog Bosun in his rooms. So he bought a bear instead – there were no rules about bears. We know that he kept the bear in a room in the gatehouse of Trinity College. We also know that Byron spent his three years at Trinity in drinking, gambling and chasing women and boys, with an occasional production of some poorish beginner’s poems, and that somehow at the end of this time he left with an MA.

We don’t know what happened to the bear, apart from a vague rumour that it died. But that was what Byron said.

So something had to get this silly young nobleman through his education, and clearly it was the bear. I called her Daisy, and saw her as a showman’s dancing bear who was getting old and over the hill as a performer, sold off to someone who could pay cash on the spot.

And there was the basis of a short story of 4000 words: Daisy observed the young waster making a mess of his life and, being a capable creature, stepped in to help. This was easy to write, as I was at Trinity myself and wasted the time much as Byron did. It was clear that when she had got him his degree he would leave Cambridge and dump her. So she anticipated that and decamped with Byron’s manservant and silverware, a reasonable deal as the servant had not been paid for several years.

It was a neat ending, but I hadn’t reckoned with the readers of Going Postal. They knew I had published some serial stories already in the form of the two Tilda plays, and the comments said clearly that they were expecting more.

Part two had been published in GP’s Sunday afternoon silly story slot. It was now Monday, and I had to write a new episode for the following Sunday and keep going. All right, I was a magazine journalist for many years and deadlines have lost their terror. So Daisy went to London with Jem the manservant and met her old master Fred on the way, and between them they resolved to set up a dancing academy for bears.

At this point a writer can only do one thing: stop trying to be creative and let the characters and the situation take over. We had three established characters: Daisy herself; the respectable middle-aged bear; her former minder Fred, a travelling showman; and Jem, the young manservant on the run with a sackful of cutlery. It was an interesting time: 1808, when King George III was mad and the country was being ruled by the Prince of Wales, and the Peninsular War was hotting up.

I allowed them a stopover in Kensington, where I was brought up and whose history I know well. Their lodgings at the corner of Hell Lane and Hogmire Lane, genuine place names, are now occupied by Mario’s pizza restaurant, reportedly patronised by Princess Diana, which I no longer patronise after two bouts of food poisoning from their salads which may have been caused by the whole district having been built in the 1860s on a thick layer of human manure from the former market gardens fertilised with ‘night soil’ from the city – what wonderful immune systems people had in former times. There was a chance for fun with the fat futile Prince of Wales, then deep in his current mistress the Marchioness of Hertford.

Then it was time to drop them in Portugal and see how well they would do in the war – and of course two resourceful men and a band of bears coped marvellously. The story was now telling itself. All I had to do was find out who was there – Paget, Moore, Wellington – and sure enough the band of bears and men would get into the plot. I owe C.S. Forester a debt of gratitude for his splendid book set in the Peninsular War, Death to the French, which shows how much can be achieved by one man with a Baker rifle but also casts a cold eye on the scene; the book is a literary equivalent of Goya’s Disasters of War engravings (two of which appear in my book).

They had to come home, of course, which was a bit of a letdown (and our own 1642 complained about it as he had been wanting more mayhem). But there was plenty for them to do. A troupe of dancing bears has to have somewhere to perform, and unless better options are available, it’s a cheap variety house. I set it in Percy Street because I have been into one of the ramshackle buildings there designed by If-Jesus-Christ-Had-Not-Died-For-Thee-Thou-Hadst-Been-Damned Barbon (just ‘Damned’ to his familiars) and the crazy tilts of stairs and floors caused by subsidence amused me. And of course the place caught fire: places like that always did. The little dark alley through which they escaped the angry crowd is still there, now called Newman Passage, and there is a little dark pub in it, the Newman Arms, where I must go if the reign of terror ever ends.

After this early failure, of course the resourceful Fred had a grander idea – buying a theatre and staging an opera, a French one because French operas had ballets as part of the spectacle and who better to dance them than our talented bears? La Vestale was an obvious choice: just premiered in Paris, the score readily available through the usual pirate network (things haven’t changed much), and a bloody silly plot even by the standards of opera. This gave scope for the usual scene (which has also not changed) of a grandstanding prima donna with a false name and a bunch of idle musicians doing their best to get away without having to waste time rehearsing (things really have changed here, greatly for the better).

And there we were, fortuitously just in time for the Old Price riots at Covent Garden and their side effects. I have made the Covent Garden proprietor Charles Kemble into more of a villain than he probably was, but it was clear that a successful upstart opera house would have been a threat to the established theatre and some kind of attack all too likely – followed, in my plot, by a false accusation of murder against the long suffering Fred.

Naturally the jury was nobbled, and poor Fred sentenced to hang. And a rescue followed as a matter of course. A new character had entered the scene, Dolores, a girl with fiery red hair, and she made her mark by playing a leading role in the escape. It was clear that she and Jem would fall in love, but first of all they had to get out of the country as quickly as they could.

I didn’t choose their destination, Russia. It was only after they had insisted on going there that I discovered that the infamous John Bellingham, who was later to shoot the British Prime Minister Spencer Perceval, was stranded on the waterfront at Archangel unable to leave and pursue his mad mission, and our gallant band turned up just at the right time to release him. These historical links just happen when you stop trying to push the plot and just let it run.

Now the last of the main human characters arrived, the rich and generous Count Bagarov, who was to be the enabler of all the adventures in the rest of the book, because you can’t have a proper adventure without a substantial supply of ready cash. So off they went, picking up a couple of polar bears on the way, as one does. Thanks to Johan Turi, the Sami (Lapp) author of Turi’s Book of Lapland, for his information on the myths and songs of his people.

Bagarov’s dream was to sail through the Northeast Passage, along the northern coast of Russia and through the Bering Straits to the far east. Today this is a routine trip for a convoy of ships headed by an icebreaker, in late summer when the ice is at a minimum. Could it have been done then, when the world was only just emerging from the Little Ice Age? Anyway, they made it.

And then we had the return voyage by the old long route, via the Indian Ocean and the Cape of Good Hope. Plenty to see and do on the way, and a visit to Batavia (now Jakarta) just in time to meet Stamford Raffles, who really was there at the time. I haven’t interfered with the time or place of any of the historical characters – they were there when the book says they were. Naturally Dolores had to have her baby during a hurricane, she wouldn’t have settled for anything less.

Finally the motley crew had to come home and settle down, and the loose ends of the plot had to be tidied up, for every comedy has to have a proper ending and you can’t just leave it with the main characters still on the run from the law. They found their home in Wiveliscombe in Somerset, a town I know well because my family comes from there. There really was, and still is, a Bear Inn where they brew their own beer on the premises. A final meeting with the judge who had presided over Fred’s mistrial, and legal matters were resolved and it was time for our heroes to Live Happily Ever After.

And there it was, a book, perhaps even a sort of novel. It had been written in thirty weekly episodes, all of them except the first two against a close deadline, but somehow it seemed to stick together as a coherent narrative. At this time 1642 had just published The Unseen Path and, ambitiously, I thought I’d follow him. He had published with Troubador Books under their Matador imprint, which is for books published at the author’s expense but a big step up from ordinary vanity publishing, as your book gets treated seriously and launched on the market in the same way as one produced by the standard firms.

So I tidied up the manuscript and sent it to Troubador, who quickly accepted it, and the mills started grinding. For much of my life I have been a freelance editor for various publishers, and was used to the production process, which is generally fairly dull. But this was different: the book was my own baby, and I was surprised by the enthusiasm of all the people I worked with.

And there was work to be done. Most of the pictures were old engravings, out of copyright and in the public domain, but some were reworked photographs of unknown origin, and these had to be replaced. (The version now on the GP site also has these revisions.) The text contained quotations in classical Greek, thanks to Daisy’s annoying habit of citing ancient authors at every opportunity, and that meant careful choice of a font that had the necessary character set. I steamrollered that problem by sending them a font I had designed myself called Orthos, and to their credit they happily accepted it.

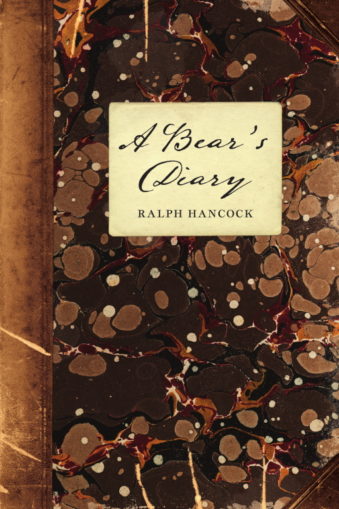

The cover design was my own idea. I wanted it to look like a real private diary of the early 19th century, in a battered old book bound in quarter leather and marbled paper, with the title handwritten on a bit of yellowed paper glued on to the cover and spine. I sent them some images, and they took the idea and ran with it. Their design is in a handsome bear brown, and the font is their choice of what a contemporary bear’s handwriting would be like – apparently they spent some time in finding this, and the result is just right.

Cover design © Troubador Books 2020

The same font is used for headings and page numbers in the text, preserving the idea of a handwritten diary, and the smaller illustrations are slotted in like pictures in a scrapbook. I’m very happy with the result, and working with Troubador has been a rewarding experience. But not a cheap one: you have to pay for what you get, and I’m not really expecting to make a profit on this publishing adventure.

The book is dedicated to you, dear Puffins. It’s on Amazon as a hardback and a Kindle ebook, and the electronic version can also be got in appropriate formats from the Google Play Store and Apple Books, if you can face shelling out for it. I hope that those of you who do will enjoy it.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file