© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

A funny thing happened on the way to Lille university. Funny for the rest of us but not so funny for my wife. She got stuck in the Metro’s automatic doors. They closed on her and caught her by the backpack. Stickers are provided suggesting, ’Beware of the Hands’ but, unhelpfully, not of the luggage. There were gasps, and cries of ‘zoot’. An engineer was called. My French isn’t very good, and I did try very hard to bribe him, but I’m afraid he let her out. It was week one, I think, of the introduction of an even more automated Lille Metro. If you survive the sliding doors to the platforms, there is another set of sliding doors, next to the platform edge, which open when a train arrives. They are lined up with the train’s doors. Think Jubilee line extension.

The little trains are already automatic. How did Le Controller Gras get that past the unions? The stations are built for eight-car trains but only four-car trains run. Be careful where you stand, as they are prone to go past you and stop at the other end of the platform. Happened to me more than once.

On this day, we have rendezvoused at Lille Gare de Flandres, from our two different Novotels (beside two different railway stations), to head for the university, to visit Number One Son, who studies there. Not trusting our sense of direction, he meets us at Gare de Flandres to escort us via the Metro, notwithstanding a mother trapped in some sliding doors.

Our stop is a distance from the university, allowing a walk through a residential area, giving us an opportunity to see how ordinary everyday Algerians, Malians and distressed Syrians live their lives. The area is called Pont De Bois and is a late post war (1970s) brutalist social housing complex of concrete boxes piled up on top of each other. The university itself, properly monikered, ‘Charles de Gaulle University Lille III’, is boxy and utilitarian, cold and windswept but nicely proportioned, clean and not at all unpleasant to walk about in.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

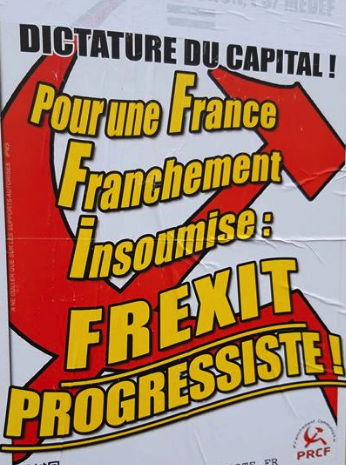

We see our first ‘Frexit’ poster, albeit from the French Communist party. We visit the library, suitably quiet, the young people refreshingly about their studies. We adjourn to a hall of residence to eat our snacks. The French have a special place for the English studying gentleman, below the stairs, underground, as if Harry Potter’s broom cupboard bedroom. Shall we call it ‘Le Salon Anglais’?

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

Imagine a fourth-class sleeping compartment on the Pakistan railways after the aforementioned has been neglected for many decades. Rather cramped, there are bars on the window, or at least a metal shutter. I made the mistake of excusing myself to le ‘en-suite’. I have, in the days of the ‘Franc’ used one of those Parisian automatic public lavatories. A sliding door opened, after slipping that Franc into a slot. Inside, nothing actually looked like a toilet. The Salon Anglais chambre de l’eau was something similar, except grottier and with foliage growing out of, what I assumed to be, a plughole.

The next part of the guided tour was the shared galley kitchen. Not quite the type of galley the Royal Navy use when roasting swan (twice a day) for the ward room’s silver platter. Rather, the type of galley that might employ rows of manacled Roman slaves, heaving oars in time to a drum beat. There was a giant American style refrigerator (perish the thought), inside of which there were individually locked and chained cold boxes. The one we were invited to examine, contained a single catering sized tin of baked beans, which, to be blunt dear reader, given the serrated nature of its bent metal top, looked as though it had been opened with the teeth. Are can openers too Anglo-Saxon?

Chastened by the accommodations we made our way back up the spiral staircase, above the humming junction boxes and steam bellowing pipes, to ground level. There are those who try to catch out a struggling author. I can hear them muttering, ‘How can there be a window with bars and simultaneously stairs back up to ground level?’ The flat ground left neglected; the French had tried to build everything on slopes. Very Alpine.

Back in the town centre we are reaching the end of our trip. We do some shopping. There’s a rather disappointing modern mall called Euralille. This is part of the Lille Europe complex built around the Channel Tunnel high-speed line’s station, which allows direct services to London, Paris and Brussels.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

Gare de Lille Europe was built in the town centre rather than as a ‘parkway’, surrounded by car parks, on the outskirts. It was completed in 1993 and is only about 400 yards from the original, Gare de Lille Flandres, on the ‘classic’ line to Paris. In another nod towards a worsening world, the giant rattle board at Lille Flandres has gone and has been replaced by daft little screens that gentlemen of a certain age can’t read. But there is a grand piano, accompanying you as you make your way to the wrong platform, to get on the wrong train.

Meanwhile, at Lille Europe, the surrounding developments are all part of one of those dreaded things, a ‘master plan’. Built for the benefit of the car, there are dual carriageways everywhere and hideous boxes to live and work in. Some are unoccupied, many are for the public sector. Do the high rises spell out ‘Lille’ in giant Lego tower blocks? I didn’t like to look.

Euralille mall contains predictable, omnipresent generic brands, amongst many empty units. It lacks high-end branded retailers, who prefer the city centre.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

However, you can spend eight hundred Euros on a Lego set. You can also buy little plastic characters to plug into your ‘Playbox Cube Three Plus’ and assume their characteristic’s when you operate ‘Fortnight’. Whatever that means and whatever that is.

There is a giant Primark. The ladies shopped there. I sat on an uncomfortable plastic bench, wedged between two North Africans, while looking miserable and pretending to charge my mobile phone.

Back at the concrete trench at Gare de Lille Europe, I’m one of those irritating people who arrive far too early. We are seated outside the international check-in, looking at the signs prohibiting machine guns, knives and unexploded ordnance, from the Eurostar trains. Why would anybody think that they could? Fashionably closer to departure time, Number One Son must return to the Salon Anglais to resume his studies.

We will not see him again for many months. As he embarks upon his own life of derring-do, we will meet again in China, in Wuhan. Or so we think. I’ve never been to China, unless their embassies count as sovereign Chinese territory, in which case I have. In our house, this is a point of contention at mealtimes, over vigorous games of ‘Been There’ and ‘Contradiction’. There is a 3D version of this high jinks (as in three-dimensional chess) when visitors from places like Marseille and Taiwan join in. As an aside, why do African’s say that they can swim when they can’t? Nasty business, a tale for another time.

From Hong Kong to Shenzhen (on the metro), to Wuhan (standing class on the ‘classic’ line), good news, change out of a tenner. Bad news, it’s a fifty-four hour round trip; standing up. A long story as yet untold, suffice it to say, life’s never dull and if the Chinese Communist Party refuse your son a bank account because they think his father is (or was) a ‘civil servant’ then you might want to stop at home (or stop in Honkers, if the tear gas has cleared).

Lille Europe’s grand piano played a mournful tune as Number One Son disappeared as if to infinity between the parallel lines allowed by the long, straight concrete box of Lille Europe’s architectural missed opportunity. Just as I was about to wipe a tear from my eye, I was distracted by a queue-less Gallic surge towards an opening Eurostar check-in.

The journey to London is nondescript, too much of it in tunnel, cutting or between train noise-reducing barriers. Looking at myself in a dark window, I reflect upon how much I despise France and the French. I hope never to go back. The new bits of Lille make it look like Stalingrad. The old bits are impressively preserved but for all the wrong reasons – the lack of a stout wartime defence against the Germans. The French bits don’t work and are full of distressed inhabitants from neighbouring continents. The bits that do work (and precisely because they do) are very Anglo-Saxon and I can see all of that at home for free.

We troop from St Pancras International to Euston, and this time, unlike fifty-plus episodes ago, I had planned it perfectly. There was time to squeeze into the first-class lounge. We shall consume our train fare in complimentary biscuits, coffee, shortbread and orange juice. But why is it called ‘first-class’? There’s nothing first-class about it. It’s like being jammed into a seventies Wimpy Bar opposite a football ground on match day, just before the fighting starts. It’s even clothed in that same horrible colour scheme.

On the other hand, the concourse at Euston is even worse, as if Hampden Park (when it held 130,000 Celtic and Rangers fans), just before the fighting starts. One super good thing is that the first-class carriages are at the ‘town end’ of the platforms, allowing one to step down the ramp and straight onto the train. Another bad thing, on our journey, no hot food owing to the lack of a chef. If this travelling gentleman didn’t look too disappointed, it may be because there was now a lot to complain to Branson about. Approaching re-fund o’clock, I was beginning to feel my trousers being stretched by a swelling wallet.

My companions announce our trip to have been a resounding success; a very welcome change of scenery, time with Number One Son and the exciting, pampered novelty of travelling at the expensive end of the train.

That reader trying to catch me out might note that I often travel in first. I do, but the family don’t. Ordinarily, I sit in luxury and pass the occasional message back to the rest of them, if I feel like it. Similarly, chastened by the hair-raising maritime safety standards in the Philippine Islands three decades ago, I always reserve a top deck cabin next to a lifeboat.

If you ever and see a fellow passenger with his pullover over his head (to simulate the middle of the night in a power failure), counting out the steps and remembering his lefts and rights to a lifeboat (like a Gurkha on the QE2 heading for the Falklands), it will be me.

On another trip, many episodes away, I am in the lift of a Scandanavian ferry for an overnight journey in the general direction of the Soviet Union. I was popping to see the family for a few minutes before bedtime. A helpful chap, with his hand hovering over the elevator buttons, asked me, ‘Which deck?’

‘Two’, I replied.

‘Crikey,’ he quipped, ‘are you sleeping in the engine room?’

‘No,’ I was forced to whisper sheepishly, ‘but the wife and kids are.’

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

Creeping out of London, our train prepares to thunder northwards. Travelling as a party of five, we are seated as a four and a one, myself being the one. Like many a couple in early middle age, my wife and I, though only feet apart, communicate by text message. The food is excellent (but cold). We are amongst our own young brood. They are happy and excited.

‘How did all of this happen to a sad, undeserving, miserable, anti-social curmudgeon like me? *puzzled face*’, I ask her.

‘Something in the jungle? *palm tree*,’ she texted back.

To be continued …

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file