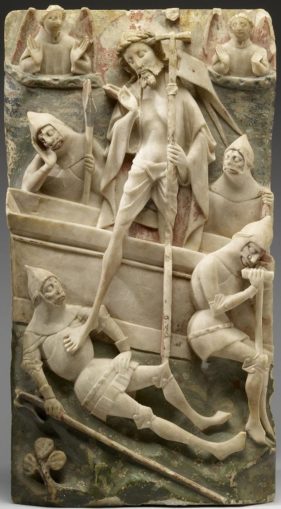

On a mini-break to London some years ago, we decided to have a look round the Courtauld Gallery (in the old Somerset House, which used for decades to be the central registry of birth, marriages and deaths, for those who remember ever getting a duplicate certificate from there!). Having crossed the magnificent courtyard, we went in a smallish, dark doorway and immediately to my right I noticed display cabinets on the wall, filled with tiny, white, ivory-like cartoony characters. Here was an emaciated Christ on the cross, an anguished-looking Mary; there were Noggin The Nog types with chainmail, pointy helmets and huge swords strapped to their belts. With their stick legs and beautiful oval faces, the figures exuded a sort of satiny glow in the dark corridor. These, I learned, were examples of English alabaster work, one of mediaeval England’s most popular exports.

Taking its name from a Greek term for a particular type of Egyptian jar, the word alabaster is used differently by art historians and archaeologists from the geological definition: geologists would say it is strictly a gypsum-based material, while museums and historians include calcite in that. Alabaster has been used since ancient Egyptian times and resembles marble, but is softer and easier to work. It appears in soft blends of white, cream, ochres, pinks and browns, occasionally streaked with red. With its soft warm glow and milky, creamy texture, it is ideal for representing flesh. As it is partly soluble in water, its main use over time has been for interiors, memorials or for portable objets d’art.

Competing with the Spanish producers, English mediaeval alabaster work is sometimes called Nottingham alabaster, as that was where the majority of workshops were clustered (although pieces were also produced in Burton on Trent and York). It was mainly quarried from thin deposits in South Derbyshire and shipped along the Trent. These English objects became very sought-after from the 1300s onwards, only tailing off in the late 1700s, often for panels used as altarpieces. Frequently polished, gilded and painted in rich colours, they depicted scenes from the New Testament such as the nativity, crucifixion or the life of the Virgin Mary, and were exported as far as Iceland, Croatia, Poland and France. Ten survive in Ireland. In an age of widespread illiteracy, scenes like these helped to bring Bible stories to life for the majority of the population. The delicacy and elegance of the small figurines is exquisite, full of life and vigour.

You can find examples in many different places: Bakewell church in Derbyshire claims to have the earliest surviving wall-mounted plaque, placed in the south aisle as a memorial to Geoffrey Foljambe and his wife, made in 1385, complete with painted coat of arms and two figures around a foot tall. There are also important collections in Nottingham Castle and the V&A. Westminster Cathedral has an example made in Nottingham in 1450 for a buyer in France, which was only repatriated in 1954 having been bought at the Paris exhibition and brought home. They were also commissioned by guilds and religious orders, and occasionally graced a private devotional setting for a rich merchant or aristocrat. Covered during Lent, they were flung open to spectacular effect on Holy Days.

Many of these figures and monuments, sadly, did not survive the Reformation – even when hidden for safekeeping. They were seen as emblems of the old Catholic order. “Our chancel floor is uneven where things have been buried’, complained a churchwarden in his report to the bishop in 1595. Following the accession of Edward VI to the throne, a number of royal injunctions were issued ordering the removal of images from English churches in 1548. An Act was passed in 1550 ‘for the abolition and putting away of divers books and images’. Fonts were defaced, stained glass smashed, walls whitewashed, mounted crosses (roods) removed. “I have digged of late in my own grounds and found a great number of alabaster images, whom (sic) I destroyed … and for such cause we lose the love of idolates”, [idolatry being the worship of images] wrote a vicar in Preston in 1574. Vandal. Some of the surviving objects were restored under Mary I, only to be destroyed a century later by the Puritans.

Later, alabaster retained its cachet as a luxury material and was still being used but in rather different and more grandiose private ways: by Robert Adam, for instance, for his elegant fireplace surrounds and for imposing columns in settings such as the so-called Marble Hall at Holkham, Norfolk. Its popularity was boosted again during the Victorian Gothic Revival. One seam, at Faulds, was in fact in use for 500 years, having been opened by John of Gaunt in the fourteenth century. It was still supplying 15-ton blocks for Cornelius Vanderbilt’s US mansion, for shipment via Liverpool, in 1894.

Always interesting to learn about things that England once did which started out seeming to be only of local significance, but, through ingenuity and skill, ended up being internationally renowned. Oh, and if you have a bit of pocket money and fancy buying one, Bonham’s sold a small example recently for £21,000.

Here is a nice blog full of examples English alabaster religious carvings, 15-16th centuries

© Foxoles 2018

Audio file

Audio Player