If ye can break my covenant of the day, and my covenant of the night, and that there should

not be day and night in their season;

Then may also my covenant be broken with David my servant, that he should not have a son

In the year of our Lord 2033, Miriam, though still young, was not a happy woman. Miriam was what our elders, bless their hearts, used to call a widow. Barely one month before our narrative begins, poor Joe and 95 others had been lost in London when they met, quite by chance, an unfortunate lorry of peace with mental health issues. Since that day, shunned by most of her colleagues at the accounting firm where she worked, abandoned by her friends, Miriam had been quite alone, but for the last four days, she had been feeling ill, to boot.

Dr Gabriel, who had been born poor and Polish, was not a young GP; in fact, he had been Miriam’s parents’ GP long before she was born.

“From the symptoms you describe,” said Dr Gabriel, “I think you might be pregnant, Miriam.”

“But Doctor,” said Miriam, “I haven’t been with anyone since Joe died…”

“That’s not at all what I implied,” said Dr Gabriel. “What I suspect is that you’re at least eight weeks gone.”

What Miriam felt upon hearing those words was a mixture of elation and sorrow.

“So, I’ll have something, or rather someone, left of Joe, after all,” she cried.

Dr Gabriel was wearing a smug smile when, two days later, Miriam returned to the surgery for her test results.

“I might be an old fart,” he said, “but I’m not often a wrong fart.” You’re in your ninth week, Miriam. And to think I was the one who told your Mum and Dad you were on your way all those years ago… I was a young man then, and the world was a much better place.”

Miriam could not refrain from giving a yelp of joy and clapping her hands.

Meanwhile, Dr Gabriel’s face had become sombre.

“Miriam,” he began, “I’m under obligation to send you for an ultrasound scan. I wish I wasn’t, but I’d end up in a labour camp in Greenland if I didn’t. In the Wagnerian Onion, relatives of terrorism victims are persecuted. As soon as they find out you’re pregnant, and they will, they’ll pounce on you. I think you should leave, Miriam.”

“I know that we’re considered deviants,” said Miriam. “I couldn’t help but notice the way I’ve been treated since Joe died.”

“Again, this is between you and me and the lamppost,“ said Dr Gabriel. “As soon as I retire, my wife and I are moving to a chalet on Mount Lebanon. The Lebanon has been quite a charming place since it became Christian again.”

“But, Doctor,” faltered Miriam, “if you go to a non atheist or non Muslim country just for one day, they dispatch you to a Greenland gulag as soon as you return. Apart from Islam, all religions have been banned. I read that Buddhists and Sikhs are leaving the Wagnerian Onion in droves, now.”

“Who said you had to come back, Miriam?” Asked Dr Gabriel. “Go to Eastern Europe, Israel or Thailand. The Earth is a big place despite all their nonsense about global villages and the like; there are still plenty of civilised countries where you and your child will be welcome. Iran itself has turned into a decent place since the Zoroastrian Revolution ten years ago.”

That evening, alone in the flat she had shared with Joe, Miriam pondered her conversation with Dr Gabriel. The elderly GP was right: the Costal State under frozen Prime Minister Leona Brezhneva was no place to raise a child. Miriam had only two relatives left in the world. Her mother Ann who suffered from early-onset Alzheimer was confined to a home. She no longer recognised Miriam whom she now only remembered as a three-year-old. Miriam’s beloved older cousin, Lizaveta, and her husband had fled to Russia a little over a year ago. Czar Volodya had immediately granted them Christian asylum. All communications with exiles were intercepted by the police. Still, Lizaveta often sent Miriam letters through kindly Russian tourists. It was in one of those letters that Lizaveta had told Miriam she had given birth to a son, John.

Making her way to Russia would be her safest bet, Miriam thought. Since her departure, Lizaveta had many times begged her and Joe to join her there. Miriam would have to travel to one of the Yiddish City States, Cologne maybe, and once there, apply for asylum in Russia.

In those derelict days, the Supreme Leader of the Wagnerian Onion was a formless creature who called herself Adolfa Iosifovna. Long ago, she had asserted her divine right to lifelong rule on account of her being Josef Stalin’s sole daughter. Somehow, the news had wended its way to the Little Father of the Peoples in the Nether Regions. He appeared to the Chief Rabbi of Germwarfare in the form of a golem, shouting and cursing horribly in Russian. The Chief Rabbi was an Armenian Jew who understood Georgian but not Russian, so he asked the old dictator to switch to his mother-tongue and the two men got along quite well.

The Chief Rabbi had a huge problem on his hands: Sangria Occasional-Cortex, the President (for life) of the Banana Republic of America, was a rabid anti-semite, her unmentionable Vice President a murderous one. There, as in the Wagnerian Onion, Judaism had been banned and Israel was getting too small to receive millions of Jewish refugees. No one ever knew what passed between the golem Stalin and the Chief Rabbi, but a few days later, Adolfa Iosifovna ceded four of her major cities to fleeing Jews. Of course, she painted it as a grand gesture of humanity and compassion, but no one was fooled. Adolfa Iosifovna secretly hated Jews and wished them all dead and buried. On a recent visit to Auschwitz, when no one was looking, she had written in pencil in the corner of a wall:

“Dear Granddad, I promise I’ll be a very good girl and finish the job you started. I love you.”

Thus, the Yiddish City States were founded. Without further ado, the New Germans were shown the City gates (literally) while the Old German city-dwellers chose to convert to Judaism and learn Yiddish (which is easy if one’s mother-tongue is German) rather than live alongside New Germans under Adolfa Iosifovna’s increasingly psychotic rule. The Yiddish City States were friendly to fleeing Christians who used them as a gateway to Eastern Europe.

In those days, the results of compulsory ultrasound scans were automatically passed on to the authorities who then ordered abortions seemingly at random. If either future parent refused, they were declared unfit to breathe Wagnerian Onion air, stripped of their citizenship and expelled.

When Miriam submitted to the pimply, ginger sonographer’s ministrations, swift expulsion was what she secretly hoped for.

“Sorry to have to tell you this, Ms. Joe,” the ginger sonographer exclaimed, looking at his screen, “but your baby appears to be a boy.”

Although Miriam hated being addressed as Ms. Her heart leapt in her chest.

“But, don’t you worry, Ms. Joe,” the ginger sonographer continued. “As soon as xe’s born, xe’ll be able to choose xes gender. Then, later on, if xe isn’t pleased with things as they are, xe’ll be able to change again.”

“Sure,” thought Miriam, “everyone knows that sex comes in liquid form and behaves pretty much like mercury inside a thermometer.”

The following day, almost as soon as Miriam got home from work, someone knocked on the door. An apparently male human together with a specimen from some university department of animal husbandry stood on the threshold. Poor Miriam had no way to know that today’s scientists have christened that species, now fortunately extinct, Homo Liberalus. The specimen introduced itself as Mx. Phat Plawd, his colleague as PC Jordan and stepped into the flat, unasked.

“Your partner, one Joe Davidson,” said Mx. Phat Plawd, “killed himself last month.”

Miriam felt a flash of anger. “My husband…” she began.

“Do not use that lewd word in my presence,” Phat Plawd interrupted rudely. “It triggers my anxiety, then I have to take three weeks off work to recover from the panic attack. Then when I’m back at work I have to fill a mountain of forms and that chips my nail polish.”

“My husband,” resumed Miriam, “and 95 innocents were brutally murdered by a Muslim terrorist.”

“That’s a far-right Nazi racist invention!” shouted Phat Plawd. “There are no Muslim terrorists, just racist degenerates who deliberately provoke unlucky gentlemen of the Peaceful Persuasion with mental health issues. Do you know that, each year, far-right Nazi racist terrorists kill seventy billion people in the Coastal State alone?”

Miriam said nothing.

“Another thing,” Phat Plawd went on, “we’ve been informed that you and Joe the racist were actually married. The only reason we keep the obscene institution of marriage legal is so that gay people can avail themselves of it. It doesn’t mean we approve when the great unwashed do the same. And now, it’s been brought to our attention that you contrived to get pregnant by Joe the racist even though he’s dead. Personally, I’ve always been convinced that racists have supernatural powers. And on top of all this turpitude, that son of Satan you’re carrying is a toxic male. Do you realise how irresponsible you are?”

“No, I don’t,” said Miriam.

“You don’t,” hissed Phat Plawd. “It’s pregnant perverts like you who give Adolfa Iosifovna sleepless nights. How dare a worm like you deprive the greatest genius, the greatest general, the greatest economist, the greatest leader of the peoples of her much-needed slumbers? That spawn of the Devil inside your your womb is already plotting the massive hole he’ll bore into the ozone layer. What do you intend to do to prevent that unnatural disaster?”

“Nothing,” answered Miriam.

“Nothing!” shrieked Phat Plawd hysterically. “Then I’ll personally see to it that something comes of nothing,” it roared before storming out and banging the door shut as loud as it could.

Something quite unusual happened the following afternoon which was Saturday. It was unmistakable, considering the sounds coming from his flat, that Miriam’s next door neighbour, Stephen, had miraculously managed to snag himself a girlfriend. Stephen was an overweight, quasi autistic young man of 21 whom Miriam rather liked and felt sorry for. His doting parents had nicknamed him Sunny, though he was anything but, and paid the rent on the tiny flat from which he rarely emerged.

Quite by chance, Miriam caught sight of Stephen’s girlfriend later that day. She was a petite brunette, about twenty, with long wavy hair and light eyes. Miriam could not help but wonder what such a pretty, intelligent-looking girl was doing with a hopeless case like Stephen.

Stephen and his girlfriend got along extremely well until the following morning. Miriam, who had a good ear for foreign accents, determined that she was from Israel. Suddenly, early on Sunday afternoon, a violent quarrel erupted between the lovers. The girl reproached Stephen with neglecting her and professed her endless love for him. How could anyone ever fall in love with poor Stephen, Miriam wondered. The girl must be out of her mind.

The teary shouting was still going on when Miriam went out to the supermarket at about four o’clock. When she returned, an hour later, the Israeli girl was leaving permanently, or so it seemed, for she had many bags with her and, incongruously enough, a roll of tattered carpet under her arm. The sad, sheepish look in her eyes nearly broke Miriam’s heart.

Miriam had almost forgotten that ridiculous episode when, on Tuesday, she found a brown envelope on the doormat. Her heart started racing even before she tore the envelope open. Inside, she found a summons to be at a certain lab nearby the following morning at nine in order to undergo a test to determine whether her unborn child carried the racist gene.

Even though the humiliating procedure took no longer than five minutes, Miriam felt so faint when she came out of the lab that she would have fallen to the ground if a tall, dark young man pushing a bicycle had not caught her in time.

“Are you alright, Madam?” He asked. “Is there anything I can do to help?”

Miriam, her head swimming, her whole body still reeling from the near fall, could not speak. The young man expertly steered her to the nearest café, sat her at a table and ordered two cups of tea.

“Thank you,” Miriam mumbled, still in a daze. “What’s your name?”

“Ehuda,” answered the young man. “I’m a tourist from Russia, Southern Siberia actually, on the border with Kazakhstan. I’ve noticed that most people here don’t know Russia at all.”

“I’ve never been to Russia,” said Miriam who was beginning to feel better, “but I know a little bit about it. You see, my cousin Lizaveta lives there.”

“You’re Lizaveta’s cousin?” Asked Ehuda. “I read about her in the paper last year. She was granted Christian asylum by our benevolent Czar and recently had a little boy called John.”

“I didn’t know Lizaveta had made the Russian papers,” said Miriam, genuinely astonished.

“She’s famous all over Russia,” said Ehuda, his voice full of awe. “She’s become one of our most celebrated Christian missionaries.”

Miriam sipped her tea in grateful silence.

“I’m so sorry,” said Ehuda, “I don’t have much time. When you’re sufficiently recovered I’ll walk you to your house then I’ll have to leave you there. I’m worried about someone, you see.”

“I feel well enough now,” said Miriam, getting up.

“Don’t think me rude,” apologised Ehuda as they walked slowly towards the block of flats where Miriam lived. “I’d love to spend time with you and talk about Lizaveta, but an Israeli girl moved into the same hotel as me three days ago. Her papa died recently at quite a young age and this has affected her mind severely.”

“Is she, by any chance, petite with long brown hair and light eyes?” Inquired Miriam, surprised. “No more than twenty?”

“That’s right,” answered Ehuda. “How come you know her?”

“She had a brief but stormy relationship with my hapless next door neighbour,” explained Miriam.

“That’s the problem, you see,” said Ehuda. “She falls in love at first sight with just about anyone. I’m really afraid she’ll come to harm, so I’ve been doing my best to convince her to return to Israel and her mama. She alone can help her.”

Meanwhile, they had reached Miriam’s front door.

“I went to Salisbury last week to see the cathedral,” said Ehuda before taking his leave. “I’ve no idea what it is with us Russians, but we’re simply crazy about cathedrals. It seems that we can never get enough of them. I stayed at a friendly little hotel in a side street just off the city centre. The owner is the sweetest man, an ex-Muslim. Here’s his card in case you ever want to see the cathedral.”

Miriam took the proffered card and dropped it distractedly into her handbag.

“Take excellent care of yourself, Mrs. Joe,” said Ehuda before vanishing into the late morning haze.

Three days later, at exactly seven o’clock in the evening, a policewoman brought Miriam an official letter, which she insisted she read in her presence. Scientists had determined that Miriam’s unborn child carried the racist gene. She was to report at her local hospital at nine on Monday morning for immediate termination of her pregnancy. Should she try anything to avert that happy outcome, she would be sentenced to ten years’ hard labour in a Rotherham disorderly house and her racist child smothered.

Miriam did not sleep at all that night. To be quite frank, she did not even try. True, at first she had been tempted to sit on the sofa and indulge in a bout of sobbing, but a voice inside her head shouted that it would be lethal to do so. So she rummaged in her handbag to find out how much cash she had: about a hundred pounds, all counted. Replacing her purse, her fingers brushed against a piece of cardboard, the hotel card Ehuda had given her three days before. He had seemed a nice, caring young man, but Miriam had no idea whether he could be trusted or not. Still, in her heart of hearts, she knew that no one on Planet Earth was less trustworthy than Prime Minister Leona Brezhneva’s police. Miriam scoured the flat and found a further three hundred pounds in sundry notes and coins. Joe had been careless with money, leaving his spare change just about anywhere in their home. She then rushed to the shops and bought a pay-as-you-go mobile phone just in time before they closed. She considered getting hair dye as well but dismissed the idea almost immediately. If they were watching her, they would guess she was trying to escape.

As soon as she got back, she shut herself in the bathroom and rang the hotel in Salisbury. A gentle, not particularly young, male voice answered on the first ring. Miriam booked a room for two nights starting tomorrow. She gave her name as Mrs. Herod who would be arriving from London, but was not sure exactly when, as she had not bought her ticket yet.

“Don’t worry, Mrs. Herod,” said the gentleman from Salisbury, “we’re not very busy at the moment. I’ll have your room ready by midday and promise to keep it for you until you arrive.”

Should the police stop her, Miriam would lie and say she was taking a day-trip to London. Her handbag and the large brown suede shopping bag Lizaveta had given her as a present long ago were all she would take. She wrapped her favourite photographs of Joe in a white mantilla he had brought her from Spain and placed them at the bottom of her handbag underneath his well-worn copy of Bleak House, his favourite novel. The shopping bag she stuffed with clothes, a few toiletries and Joe’s toy elephant from his childhood.

Before seven, the following morning, Miriam was at the station. The next train for Salisbury went all the way to London; so, to be on the safe side, she bought a ticket to London. Changing one’s mind and hopping off the train before reaching one’s final destination was not (yet) illegal.

The hotel owner, a slight man of about fifty, stood behind the counter in the plain lobby when Miriam pushed the glass door open.

“Mrs. Herod, I assume,” he said as soon as Miriam stepped inside. “Welcome. My name is Tameer. Let me show you to your room. You must be tired after your journey.”

He took a key off a hook and led Miriam up the stairs, past a sunny terrace, to the first floor. The room was simple but extremely clean.

“We have a reading room downstairs and some computers,” Tameer said. “Also, my wife serves home-cooked Egyptian food on the terrace. It’s healthier and cheaper than eating out. We live in a flat across the terrace from your room. Don’t hesitate to come to us if you need any help.”

“Are you from Egypt,” asked Miriam.

“Yes,” answered Tameer. “A beautiful but cruel country, Egypt.”

Miriam fell into an exhausted sleep as soon as she was alone. She woke up five hours later, furious with herself for wasting time sleeping when she should have been planning her flight to Russia. She took a quick shower then ran downstairs to ask Tameer for a light meal on the terrace and the key to the reading room.

Tameer brought Miriam a tray of fragrant food.

“My wife would have liked to bring you this herself,” he said, “but since our daughter and her family were murdered she often finds it hard to get out of the flat.”

This revelation shook Miriam to the core, but she refrained from asking any question. She had so little appetite that she could have eaten nothing if the food had not been delicious. She was alone on the terrace, apart from a foreign-looking man, about her own age, in a reddish t-shirt, sitting at the other end drinking beer.

After dinner, Miriam made her way to the reading room on the ground floor. She ignored the three computers sat on the desks. The Internet was so heavily censored, it was practically useless. She and Joe never used it. The reading room contained a large section called “Leaving Islam.” Apostasy was considered racist in the Wagnerian Onion, though only when applied to Islam. When caught, Muslim apostates were sent to Greenland, or sometimes even handed over to fellow Muslims who swiftly beheaded them.

“How low we’ve sunk,” Miriam thought.

There were many classics in the reading room, which surprised Miriam. Practically all classic literature had been declared racist decades ago and banned. Plato and Aristotle were called monsters, modern writers such as Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie were depicted as criminals. When Joe’s parents had died, Miriam and Joe had discovered boxes upon boxes of books hidden in the darkest corner of the loft and had still been devouring Shakespeare, Dickens, Dostoyevsky and many more when Joe was killed. A book case against the back wall bearing the label “Soviet Dissidents” meant nothing to Miriam. She went back up to her room to think some more.

Miriam sat on the bed cradling Joe’s toy elephant, which had been his favourite possession in the world. His paternal grandmother had made it for him just before he was born. There were three tiny buttons at the back so that the outer cotton cover could be removed and washed. It had been been so cleverly stitched that the buttons were completely invisible. Was it Miriam’s imagination? The little elephant felt heavier somehow and there was an odd, rustling sound inside. She turned it round and unbuttoned the back. Instead of the well-known stuffing, she found a white linen bag she recognised as having come with the only pair of expensive shoes she had ever bought. Her heart pounding she unstrung the bag: wads of banknotes and a rolled-up piece of paper lay inside.

Although the paper was in Joe’s handwriting, it made no sense to Miriam. Why had he made a list of buildings and campsites, at least one in each county and big city in the Coastal State, followed by what appeared to be a mobile phone number? They bore Russian-sounding names Miriam had never heard of, Vladimir Bukovsky, Aleksander Zinoviev, Andrei Sakharov… She went down the list slowly, read it a second time, a third time, but still, nothing made sense. She turned the paper over. The back was blank. Suddenly, she remembered something, she did not know what. She read the list for the fourth time until she reached a name: Alexander Solzhenitsyn. She had seen that name before but, for the life of her, could not think where.

Miriam got up to wash her hands. As she was drying them, she recalled where she had seen the name: on the spine of a book called Cancer Ward downstairs in the reading room. She ran down the stairs to the reading room, shut herself inside and stood in front of the “Soviet Dissidents” bookcase. The buildings and campsites Joe had made a list of bore the names of writers! The Wagnerian Onion had obviously worked hard at concealing their existence for, even though many of them had been quite prolific, Miriam had never seen their writings anywhere. She picked up Cancer Ward and read about the author. “Poor man,” she thought.

Miriam read for an hour. The writers on Joe’s list had the same thing in common: they had been accused of crimes they had never committed and sent to labour camps for many years. “It’s exactly the same as what they do here,” thought Miriam, “except that here, they accuse you of racism rather than sabotage, speculation, or intelligence with the enemy.” She opened a volume entitled Within the Whirlwind. The summary on the back cover was harrowing: the author had worked as a nanny at infant day care centres inside Siberian labour camps. A folded piece of paper was tucked between pages 162 and 163. It looked the same as Joe’s list, except that it said at the top: “Secure Accommodation for Dissidents within Great Britain.” Miriam loved that. Calling the Coastal State by its real name had been a crime for many years.

Miriam galloped back up to her room, sat on the bed and checked Joe’s list against the one from the reading room: save for the missing title, they were identical. Because she loved Exeter Miriam selected the Aleksander Zinoviev Building and, her fingers shaking, dialled the number. A woman picked up before the phone had even started ringing.

“My name is Mrs. Joe,” Miriam began.

“It’s enough,” the woman said in a neutral tone. The line went dead.

Miriam sat on the bed, nonplussed. Because she was very tired and it was getting late, she decided she would not try the other numbers on the list until tomorrow. That night she dreamt that Mx. Phat Plawd had managed to come into her hotel room even though it was locked and stood above the bed uttering threats, a malevolent smile on its face. She woke up at dawn shouting “No!”

Shortly after eight the following morning, someone knocked on the door.

“Who is it?” Asked Miriam, instantly alarmed.

“It’s me, Tameer, Mrs. Herod.”

Reassured, Miriam opened the door.

“Someone’s just brought a letter for you, Mrs. Herod,” said Tameer handing her a small white envelope.

“A letter for me!” Exclaimed Miriam. “Who gave it to you?”

“An elderly lady,” answered Tameer, “quite respectable.”

Miriam slit the envelope opened carefully. Inside was a short note.

“The ___ ___ Building is full. However, I have passed your request for shelter on to the campsites. One of them will be in touch shortly. Destroy this letter once read.”

Miriam did not go out that day. In fact, she did not go out at all all the time she was in Salisbury. She spent the whole of Monday wondering how the dissidents, for, surely, it was what they were, knew so much about her. At six o’clock Tameer brought her another letter.

“A quite man gave it to me,” he told Miriam, “quite respectable.”

“The ___ ___ campsite is able to offer you accommodation. Don’t hope for anything luxurious. A red Mini (a real Mini, not the German rubbish) will wait for you outside Barnstaple railway station at 12 noon on Wednesday. An elderly lady will be at the wheel. You can’t miss the car: a small brown dog with a purple collar will be sitting on the front passenger seat. The lady will say, “I hope you like dogs.” Answer, “I love them,” and get into the car. Do not say anything else. The lady will drive you to the campsite. Destroy this letter once read.”

Tameer insisted on driving Miriam to the station on his moped and stood on the platform until the train had pulled off. Strangely enough, he had suggested his wife give Miriam a haircut on Tuesday. Mrs. Tameer was a sweet lady who spoke hardly at all. The pain in her eyes shook Miriam to the core. Miriam’s heart hammered in her chest all the way to her destination even though her journey was uneventful. A man in his late thirties, his fair hair greying, sat across the aisle from her, reading a caravanning magazine. He wore a gold wedding band, which surprised Miriam. In the Wagnerian Onion, unless they were gay or Muslim, people hid the fact that they were married. The man vanished when they reached Exeter. On the second leg of the journey, an old man studying a Russian grammar book sat next to Miriam. Russian-learning was discouraged in the Wagnerian Onion. Those who spoke Russian were, more often than not, accused of intelligence with racist white supremacists and sent to Greenland.

It was sunny when Miriam stepped out of Barnstaple railway station. There were few cars on the concourse, so Miriam spotted the red Mini immediately and made her way to the driver side. The lady rolled her window down.

“I hope you like dogs,” she said in a neutral tone.

“I love them,” answered Miriam before getting into the car.

The little dog settled on Miriam’s lap, gazing at her with adoring eyes. They rode in total silence through lovely countryside until they reached a dirt track. The lady stopped her car at a white metal gate in the middle of a tall fence. The gate opened and a young man stepped out. Miriam’s heart froze inside her chest: the young man was PC Jordan! He ambled to the Mini.

“Hey, Dasia, you old spook,” he guffawed, “give everyone’s favourite double agent a hug.”

Dasia got out of the car, hugged PC Jordan without a word then walked towards a middle-aged lady who had just appeared at the gate. Dasia stopped and kissed her cheek. At that precise moment, joy exploded inside Miriam, for the woman whose cheek Dasia had just kissed was Lizaveta.

Miriam jumped out of the car, upsetting the little dog in the process, ran to her cousin and, embracing her with all her might, asked breathlessly,

“Lizaveta, how come you’re here?”

“Dasia called me to say you were on your way,” explained Lizaveta, “so I flew over to be here when you arrived.”

“But isn’t coming back dangerous for you?” Worried Miriam.

“Not at all,” said Lizaveta mysteriously. “You’ll learn our dissident ways as you go along, dear Miriam.”

She put her arm around her cousin’s shoulders and gently guided her past the gate into the campsite.

“I won’t be able to stay for long,” apologised Lizaveta, “but I’ll come back in time for your baby.”

Miriam was pleasantly surprised: the campsite looked lovely. Colourful caravans, rainbow camper vans stood harmoniously next to small bungalows and wooden cabins along a circular path. An attractive woman approached Miriam and shook her hand.

“I’m Mrs. Gideon, Rosie for short,” she said. “My husband who’s one of our leaders will be back shortly together with Mr Cohen. Meanwhile, let me introduce you to Selina and Mrs. Cohen.”

Mr and Mrs. Cohen, whom my esteemed readers met in the last instalment of this magnificent saga, had given up their London flat after many tribulations and moved into a two-room bungalow at the Andrei Sakharov campsite. Although Gideon’s dog Marius was at present pretty senior, his passion for Mrs. Cohen, now in her eighties, had never abated.

Presently, two gentlemen arrived riding an old-fashioned scooter. Miriam’s heart did a somersault when she recognised the married caravan enthusiast and the elderly Russian student from the train.

“Here they are,” said Rosie merrily. “Miriam, meet Gideon and Mr Cohen. Simon’s his name.”

Miriam shook hands with both men.

“We’re so glad you’re here, Miriam,” said Gideon. “Why don’t we all go and sit outside our caravan? Is Savannah around?”

“She’s at the shack,” said Mrs. Cohen. “Selina, do call her, please.”

As they all took a sit on garden chairs Miriam noticed a large army tent in the centre of the campsite. Grey-suited, Slavic-looking elderly men came in and out, sheaves of documents in their hands, chatting to one another and smoking cigarettes. Before she had even had time to inquire, Gideon explained:

“They’re this week’s batch of KGB agents.”

“KGB!” Exclaimed Miriam, shuddering.

“Dasia has a particular fondness for KGB agents,” Gideon resumed. “They arrested her five times when she worked in the Soviet Union. So, she’s founded the Royal Society for the Protection of KGB Agents. They’ve become an endangered species, you know. They were so grateful, they repented of their evil ways and now come every week to teach us useful skills such as infiltration and influence.”

“But, weren’t they thugs?” asked Miriam timidly.

“They weren’t thugs,” said Mr Cohen. “They were ordinary men in an evil system. Plus, they were the ones who built and started this monstrous machine which has the gall to call itself Liberalism; the least they can do is show us how to stop and reverse it.”

Meanwhile, a diminutive woman with long, chestnut-brown hair had joined them.

“Miriam,” said Rosie, “this is Savannah. Believe it or not, Savannah is our carpenter.”

“Savannah is a genius at her trade,” Gideon took over. “She built her cabin with her own hands,” he added, pointing at a beautiful blue hut. “Recently, we requisitioned a small piece of land adjacent to the campsite. Using our enemies’ own methods, we claimed it would be racist not to hand it over to us. An old shack stands on it. We’ll show it to you in a minute. If you like it, Savannah will transform it into a comfortable cabin for you and your son to live in., Mr and Mrs. Cohen have offered to take you in until it’s ready.”

“I really wouldn’t want to impose on your kindness…” Miriam began.

“You’re not imposing,” interrupted Mrs. Cohen. “We love children here. We even have a small school, nannies, a doctor and a midwife.”

“Why don’t we all go to the shack?” Said Lizaveta. “I’ll have to leave with Dasia soon.”

“Doesn’t Dasia live here?” wondered Miriam.

“No one knows where Dasia lives,” answered Gideon.

“Dasia lives in the Soviet Union,” quipped PC Jordan. “Dasia may have left the Soviet Union, but the Soviet Union never left Dasia.”

“Don’t mind Jordan,” said Gideon, laughing. “He’s our resident jester.”

The shack was old and stood in the middle of a lovely meadow. Miriam asked her hosts to leave her alone for a few minutes. A ray of sunshine came in through a gap between two planks. Miriam took out of the bag her favourite photograph of Joe, which she had taken herself shortly after their wedding, and fixed it to the wooden wall. Then she stood in silence, she never knew for how long, gazing at Joe’s beloved face.

“This is our home,” she told her new friends when she came out.

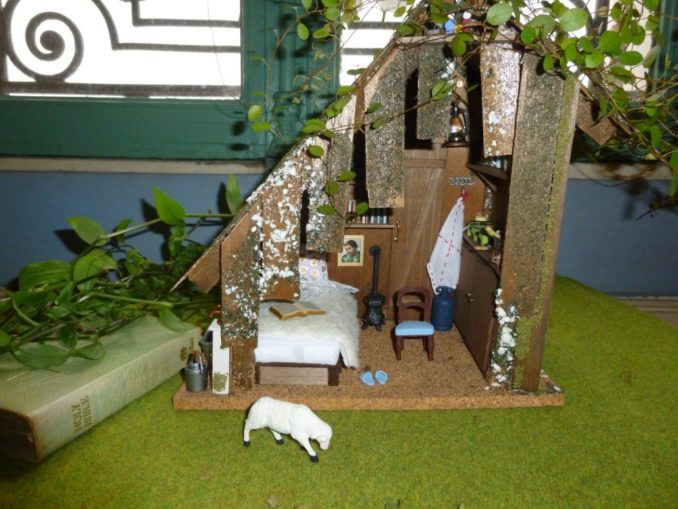

It was now December, cold and snowing lightly. Miriam’s baby was due any time soon. Though the Cohens had insisted she stay at their bungalow until after the birth, Miriam had moved into the shack as soon as it was ready. Savannah had made a magnificent job of it: a bed with a large drawer underneath, a worktop, shelves, cupboards… The KGB agents had magicked a perfect little stove which kept the shack at ideal temperature.

That morning, Miriam announced that she had decided she would give birth alone in her shack, guided by Joe’s spirit. Despite many misgivings, the campsite inhabitants respected her choice, but made her promise she would call for help if anything went wrong, or she simply changed her mind.

Everyone prepared for a long, sleepless night. Mr and Mrs. Gideon, Selina and Savannah settled to a game of Monopoly in the Cohens’ living room. Mrs. Ida Noodle, the campsite cleaner, did not return to the village, but stayed drinking tea (and stronger beverages) in the campsite office with Lizaveta, who had come back as promised, and PC Jordan. Inside their tent, the KGB agents lay on sleeping bags, drinking vodka and eating smoked sausages. Dasia, who did not like children, sat in her car, rereading Crime and Punishment.

Towards eleven the snow began to fall harder, blanketing the campsite in total silence. At midnight, in Miriam’s shack, an infant cried.

© text & pictures Doxie 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file