September 5th, 1809.

It has been a busy month. Our aimless wanderings took us to Guildford, where we have been encamped in a tumbledown barn. The farmer is quite content with our presence, as we are usefully reducing the numbers of rabbits, wood pigeons and other pests that would otherwise have despoiled his crops. For our part we are happy to walk down the edges of fields, close gates behind us, and generally behave as responsible people do in the country.

Occasional performances in the inns of Guildford and on village greens bring in enough money for our modest needs, but on most days we practise our skills in a clearing in a nearby wood. Bruin’s fire eating is now of a high standard, and he has progressed from the simple skill of extinguishing torches with which every fire eater begins his act, through the more advanced tricks such as transferring a flame from one torch to another on his tongue, and finally to the spectacle that the audience are waiting for, the ‘blow out’, in which he appears to shoot a long jet of roaring flame from his mouth.

The torches are metal rods with string bound around the tip to absorb a small amount of ordinary lamp oil. There is not much heat in them, and the flame can easily be extinguished by putting the torch in the mouth to cut off its supply of air – though the flame is real enough, and blisters are a constant trial to the performer, who simply learns to ignore them. The ‘blow out’ is done by taking a small amount of oil in the mouth a blowing it out in a spray past a burning torch which ignites the vapour. Bruin has to be very careful when performing this trick in the yard of an inn with a thatched roof, and we always have several buckets of water on hand – something that would have saved Jim Crint from the loss of his theatre.

Little Henry’s Velocipede act has developed in a surprising way. He had become adept at balancing tricks, including riding his machine poised on only the back wheel. However, he was limited by the fact that it can be propelled only by putting a foot to the ground and pushing it forward, which limits the length of any trick to a few seconds.

While watching him practise, the ingenious Jem was struck by an inspiration. The ordinary grindstone used for sharpening knives, sickles and swords is kept in constant motion by turning a crank handle. Jem thought, What if the principle of this handle could be used to turn the wheel of a Velocipede, and thus keep it in uninterrupted motion? He and Fred went off to a blacksmith to get the necessary metalwork done, and the result is a most curious machine. It has a single wheel turning upon an upright wooden fork at the top of which is a padded leather saddle. At each end of the axle is a crank, the two facing in opposite directions so that they can be pushed alternately with the hind feet, through wooden blocks free to rotate on the handles – or I should say ‘pedals’ – which are shaped so as to be easily gripped by a bear’s claws. I have christened this device with the impeccably Latinate name ‘Unirota’.

Henry was happily astounded by this unexpected gift, and has learnt to ride the Unirota in a few days. He now goes everywhere balanced on his machine, as if it were his natural form of locomotion. It has a particular advantage in that it leaves the rider’s front paws free, and Angelina is now teaching him to juggle.

Peter and Emily have abandoned their notion of a seesaw performance after a third plank broke under their combined weight. Perhaps this art is more suited to lighter creatures such as humans. They are now learning to walk on a slack rope. We found a length of strong hempen rope in a store outside the town’s House of Correction, and had no hesitation in appropriating it, for it was destined for the attention of the unfortunate prisoners who would have had to unpick it to make oakum, strands of hemp which are mixed with tar and used to caulk the seams of ships. Now the rope is stretched between two stout trees, and the ground shakes with heavy thuds as one of the bears falls off yet again. But they are undaunted. As Plutarch says, Πᾶν τὸ σκληρὸν χαλεπῶς μαλάττεται, Everything that is hard is softened with effort.

September 10th, 1809.

We have had two pieces of good news. Fred has visited London. For the journey he borrowed one of the farmer’s horses in return for the trifling payment of six brace of partridges, and he has just returned and restored the placid grey gelding to its owner.

His friends – he has friends everywhere – told him that Jim Crint’s baseless accusation against us bears that we started the fire in his theatre has evaporated, and indeed has Mr Crint himself. It seems that he had insured the theatre against fire, which is only prudent as these places constantly burn down, but that the policy did not cover him against a fire caused by his own negligence. He had indeed been careless in his penny-pinching way, for he ought to have rendered the drapes fireproof by painting them with a solution of alum, and had not troubled to do so. By calling a hue and cry upon us, he had hoped to divert attention from his own failings; but the insurers would have none of his story and refused to pay. Pursued by many creditors, Mr Crint has vanished into the wings, and let us hope that his re-entrance is not in the script.

To our delight Fred told us that he had visited the Admiralty, where he was greeted with the most welcome news one could imagine. The prize court has decided to buy Incroyable, the French privateer vessel we captured, for £1750 – that is, £250 more than we had expected. The extra price was decided in view of her usefulness as a small speedy ship of war, something of which their Lordships stand sadly in need, as our shipyards still cannot match the French in the construction of such vessels.

We have stayed too long in the provinces. Our performances are well rehearsed, our company of bears and men unprecedented. It is time to return to London and show off our skills. Our goal is, in the immortal words of Homer, αἰέν ἀριστεύειν καὶ ὑπείροχον ἔμμεναι ἄλλων, always to excel and to be better than others.

September 17th, 1809.

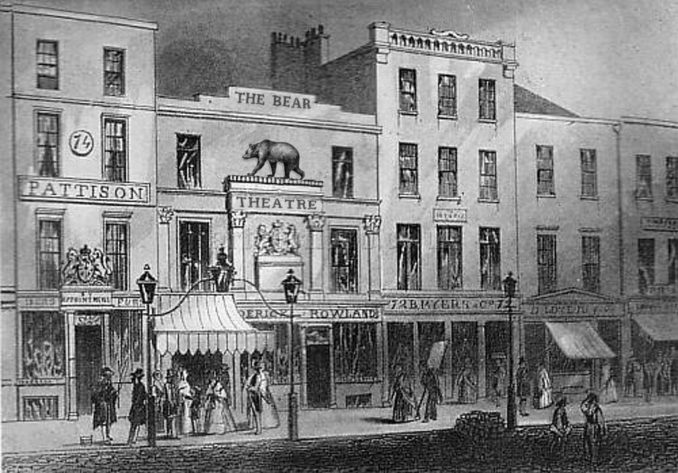

We are returned to London. With our new-found riches, Fred has secured the lease of a theatre in Oxford Street, and we have not delayed in renaming it The Bear Theatre, and have installed a painted plaster statue of a bear on the front. It is spacious but a little decayed and shabby. However, a lick of paint here and there has restored it to an acceptable state. The bears have been helping with a will, and we all smell of the turpentine we had to use to remove the splashes of paint from our fur. Sometimes humans, with their removable clothes, are at an advantage.

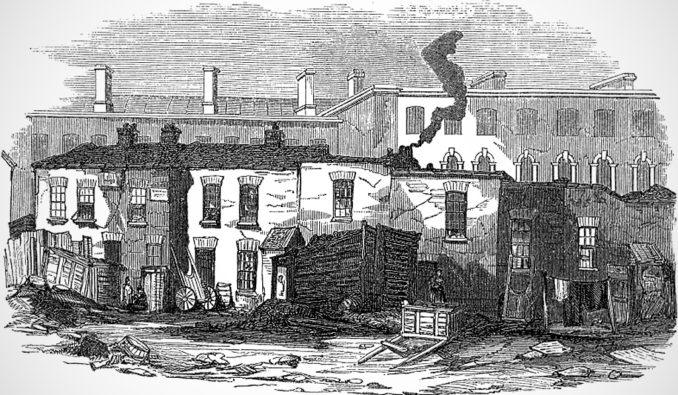

We need to live close to the theatre, and Fred has secured us premises in Bell Street, off the Edgware Road and a little way to the north-west of the theatre. The building will soon be demolished to make way for a new row, and it is in a tumbledown condition, but we have seen far worse and it will serve for now.

September 20th, 1809.

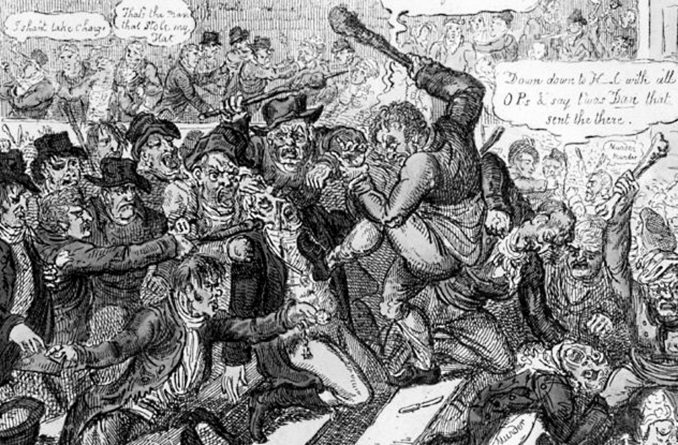

There has been much excitement in London. The old opera house at Covent Garden had burnt to the ground a year ago – a common occurrence for all theatres, of course, and how we all wish for a system of lighting that does not involve naked flames! It has been rebuilt, and on the 18th it opened for its first performance, not yet a full opera for which they are not ready, but a staging of Shakespeare’s Scottish play, which I will not name for fear of bringing bad luck on ourselves. And indeed, the traditional ill fortune associated with this play has manifested itself.

To defray the great expense of rebuilding and furnishing the new theatre, the management has been obliged to raise the price of admission. They have been quite modest in their demands – for example, a ticket to the pit, which used to cost 3s 6d, now costs 4s. However, the increase incensed the public, especially those who bought the cheapest tickets, and their protests grew into a riot which spilled out into the surrounding streets.

Last night the disturbance continued, and it seems that it will continue for some time. The slogan of the rioters is ‘Old Prices’, and they carry banners with the letters OP. Performances at the opera house continue with difficulty, but the conflict cannot be sustained and one side or the other must yield.

September 21st, 1809.

‘Right,’ said Fred, ‘we’re goin’ to ’ave an opera.’ He has somehow secured the score of La Vestale, a work by the fashionable composer Gaspare Spontini, which created a sensation at its first performance in Paris two years ago. There is a distinct advantage in such a choice: since we are at war with the French, we are at liberty to pilfer their creations without paying them. Thanks to this economy we can stage our performance at ‘Old Prices’, and we shall have little difficulty in drawing audiences away from the other place.

The libretto is in French, and I am now translating it into English for our performance. That is in itself a novelty, since the opera house at Covent Garden performs its works in Italian, and most of the audience have little idea of what is supposed to be happening on stage.

The plot is risible, as is usual in opera. It is set in ancient Rome, and the heroine is a Vestal virgin, Julia, who is pledged to perpetual virginity and charged with the upkeep of the sacred flame at the temple, which must never be allowed to go out.

Of course – for this is an opera – she is in love with a Roman general named Licinius. Though she strives to shun him and attend to her duties, she is obliged to present him with a wreath when he returns from a successful campaign. The inevitable consequence follows, and while the two are dallying at the temple she forgets to add fuel to the sacred flame, which goes out.

For this grave breach of her duty Julia is sentenced to be buried alive – the Romans were not slack in their administration of punishments. But, by a divine miracle, a thunderstorm relights the flame, and this is taken as a sign that she should be spared – and into the bargain, that she should be released from her vows and allowed to marry Licinius. As it is said, tragedies end with a death, and comedies with a wedding.

September 23rd, 1809.

Fred has engaged a band of musicians and singers, on the strict understanding that they must attend all rehearsals and no substitutions are possible, except in the case of genuine illness.

To play Julia, we have found a young singer named Adelia Catelani, a name to conjure with – though she is not the famous Angelica Catelani who performs to huge acclaim and huger fees in Covent Garden and elsewhere, but her sister-in-law. Nevertheless she sings prettily enough, and we are all delighted with her. In the usual French style, the opera begins and ends with a ballet, and of course it is we bears who will be performing here. They do not have such attractions at Covent Garden.

Fred’s plan is to stage our own performance every afternoon, and the opera in the evening. It seems a thoroughly sound idea – and let us hope so, as we have invested all our capital in the lease and repair of the theatre and the hiring of the singers and orchestra. To quote Plautus, Videte, quaeso, quid potest pecunia, See, I pray you, what money can do. Let us hope it does what it can.

We are all busy with rehearsals, and eagerly await the first performance on Monday the 25th.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file