IT PAUSES, MONDAY BEFORE EASTER, HOLY WEEK

An early morning start for the whole household, Martha, Iltud, Sally, Josey, Narin and an insistent Sam, who refused to be left behind; fresh clothes, big breakfasts, a stroll down to the station to catch the first train to St Josephs. What Narin made of it all they struggled to see; she had caught something of the excitement from them, but was clearly nervous, pressing in between Sam and Martha on the train seats for comfort and reassurance. Her progress in learning English was continuing, mastering many everyday nouns, some simple pronouns, a few common verbs, and she was now haltingly trying to put some together in rudimentary phrases. She was bright; they could all see that and very eager to communicate after years of isolation.

It was a sunny day, mixed with oncoming clouds, a freshening sea breeze tempering the air with its south-westerly mildness. Docco was fussing over them, employing a blissfully happy Josey as his assistant guard, helping to check tickets, wave the flags at the various halts, miming unrequested explanations to Narin who looked at him in bewildered amusement and then, in Josey’s brief absences, watching the countryside rolling by, the little villages, churches, farms, wooded and flowered slopes rising above, the river at the bottom, occasionally asking for the names of what she saw. Two stops down the line Brother Peran clambered aboard, blessing the carriage and then filling half the bench seat opposite them, grinning broadly, telling stories of the sites they would see. The girl smiled at the sight of him and started to relax, clearly in her mind if he were going too it would be fine. He soon had them all laughing, even Narin and Sally, who realised that any chance to pump him for more information on this part of the trip was highly unlikely.

On arrival at St Josephs they walked up the main street to the Town Hall and then split up, Sally, her son and the priest headed down to the harbour to Thea’s to wait while the others went to the Town Hall for Narin’s interview, Sam muttering what was the point as no one could talk to her? Sally’s party would wait for the Abbot to return from the Town Hall and then head over with him, by boat, to the island Abbey.

Thea’s face lit up when Sally, Josey and Brother Peran came in, evidently regarding the monk as another island of culture and learning in her exile. Refusing all offers of payment, she ordered up small pastries, coffees and warm milk for Josey, joining them, asking how Peran’s studies were going and why they had come to St Josephs, calling in her family to show them off. Even Georgy, initially sulky when he realised Sally was one of the recipients of his mother’s earlier generosity, warmed up on learning of her friendship with Sam, recounting how they had rescued the girl and asking after her. He let slip that they had been warned they would be going back soon, more tasks to complete and so on, exactly what they were, he claimed not to know. Sally wondered how Martha and Narin would take the unanticipated early return of Sam to the outside, but Georgy seemed raring to go as if straining to complete unfinished business.

Thea though was not to be baulked of her desire to hold court for long. “I see,” she said looking at Sally, and smiling, “that Anna here keeps her promises to visit a lonely old woman, as does my favourite priest Brother Peran, unlike that ungrateful Iltud… Tell me Anna, how is Martha faring with my finest cloth. Will she, you, do it justice, resemble a Byzantine princess, and become an object of majesty and beauty?”

“I still can’t thank you enough Theophano,” the old lady was delighted by this reverent pronunciation of her full name, “for your unbelievable generosity, I did not fully appreciate it at the time. It is a thing of beauty, but the most beautiful thing about it is how it has helped raise the spirits of the young girl Georgy helped rescue. Martha says she is a far more skilled needlewoman than herself and the task has helped bring her back to life, perhaps it’s helped her realise that kindness and generosity can be found even when you are so far from home.”

She could see her host was pleased by this little speech, as was Peran who was beaming exuberantly. “When they have finished hers they will make mine, in time for the new arrivals Easter ceremony at the Abbey, I don’t have the skills to help.”

“Yes,” Thea replied conspiratorially, “but you have others, or so I hear, even more valuable to the cause.”

She caught Peran flashing Thea a warning look, and this time the little dynamo retreated a little.

“I’m sorry Theophano, what do you mean by my skills, my languages and what cause?”

But Thea would not be drawn any further and in any case the others arrived and poured out their news that Narin’s interview had been just a formality, Peran’s written character witness and Iltud’s verbal summary settled the matter in five minutes, everyone smiling at Narin, a few with tears in their eyes, especially the Abbot himself. The only point of discussion had been her future, but the consensus was to wait for the Byzantine embassy, which was expected soon, and ask them, and likewise the mysterious unnamed ‘he’ everyone kept alluding to. Besides, it should be her decision, not theirs, and so they needed to wait for her to be able to speak with them well enough to discuss it if neither of the former could help. Narin was clearly completely mystified by it all, confused by the constant mentions of her name by strangers.

Thea had insisted she sat between her and the priest, and seemed to have taken on the role of her adoptive great aunt, offering cakes, anything, until Peran managed to convey to the girl by a mix of gestures and words that it was Thea who had given her the cloth. Tears flowed, hugs, almost prostration, embarrassing even the old lady, who insisted she follow her into the cloth room and see her stock, emerging fifteen minutes later with a fine white silk headscarf and matching waist band, the girl completely over-whelmed, Georgy just rolling his eyes in mock resignation. It was at that point that the Abbot arrived and came in to ask them to follow him to his gig for the trip to the island, but the thing that took Sally’s attention was a brief sotto conversation in Greek between Georgy and his mother, her face conveying a savage desire, bright and hard, almost without limit. Then as she finally got out, having thanked her hosts effusively once more, she overheard a snatch of a muttered conversation between Georgy and Sam, their expressions composed into blankness, “now do you understand…”

The gig ride took about ten minutes to cross the calm sheltered bay water, coming into a little landing stage below the Abbey. The Abbot, Brother Winwaloe, was full of solicitous enquiries of her, Josey and Narin, her accommodation, hosts, everything other than what she wanted to know, jokingly enquiring of her if Brother Peran really took his parish duties seriously or did he devote all his energies to his scholarship?

Sally could see this was something of a running joke between the two of them. He told Peran he could borrow a further three books from the Abbey Library and to meet them in the refectory in an hour. In the meantime he would show Sally and her son the Abbey and a little of the island; Peran later telling her this was a most unusual honour.

The Abbey was clearly ancient, but newer than the Basilica and built in more typical ancient Celtic ecclesiastical style, albeit with what looked like a parish church sized, Romanesque bell tower at the eastern entrance. It was surprisingly small and simply furnished in comparison with the town’s Basilica, white-washed rendered internal walls and all flagstone floored, other than by the altar where what looked like Byzantine tiles had been laid: small plain glass windows, gold and brass candelabra with carved oak seating in the two small side chapels only. The Abbot explained that the Abbey church was really only for use by the monks who lived there, about a dozen in total, who were the most scholarly of all and spent their time studying and practising the arts familiar from the Lindisfarne and other Celtic gospels. The only other regular congregants were the Duke’s personal retinue, based in the ancient fort at the summit of the island about half a mile away, around a dozen guards and the same number of servants. The Brothers lived in a small cluster of cells with a library, wash-house, storerooms and workshops, situated between the Abbey and the southern shore.

He was in a mood to talk, to explain, needing little encouragement from her. The Duke was an old man now; reclusive since a bad injury and the death of his wife long ago, only indulging in state business on Easter Day each year, otherwise everything was run by the Council. Since the start of contact with the Byzantines, who apparently had an insatiable appetite for vellum books illustrated by the Abbey’s Brothers, paying extremely high prices for them, and the advent of more immigrants from Logres, life in the Pocket had improved significantly. The population and the land itself were growing again, it was clearly His doing, confidence had returned, and they felt they were being directed to start to play a more active role in the world again.

Did he believe that stuff about the Pocket being set aside by God as a final refuge, an entry point?

Of course, wasn’t it obvious, could there be any other explanation?

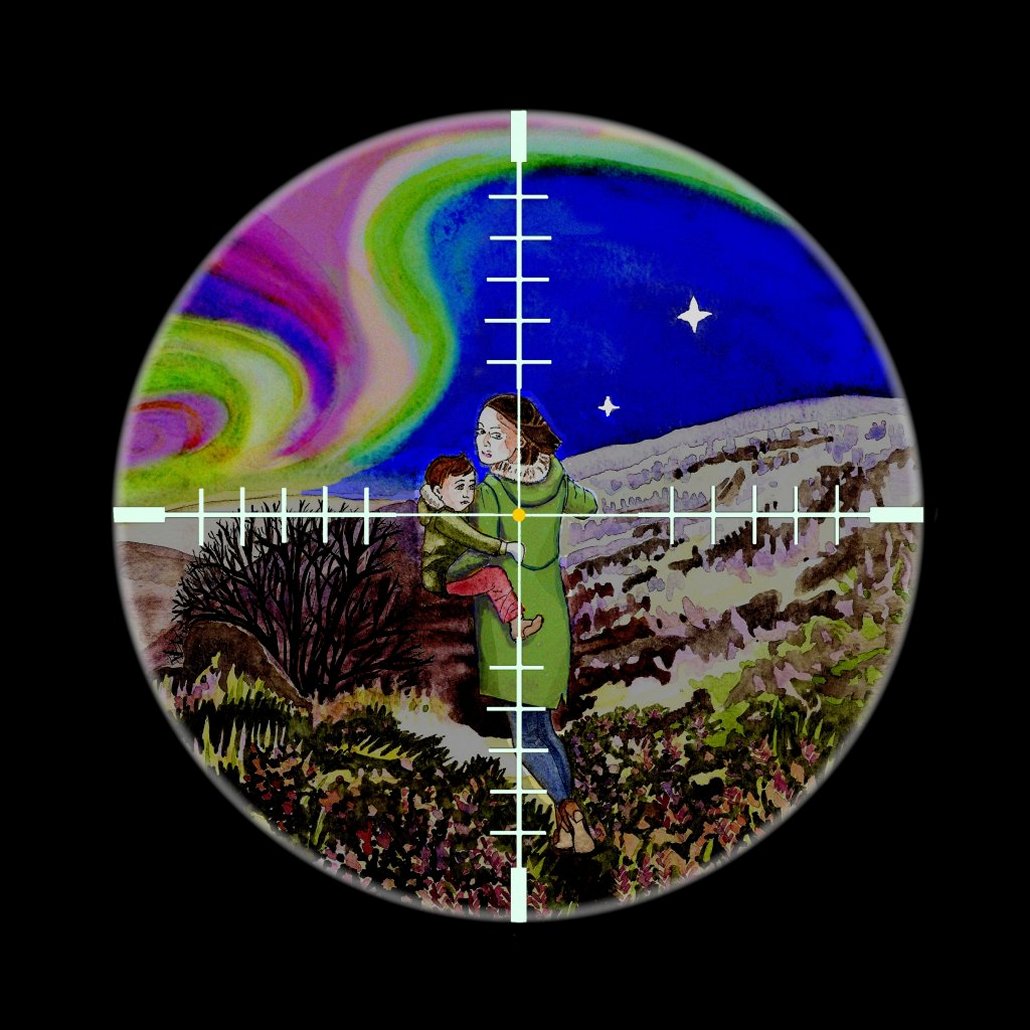

What were they trying to do, sending armed parties into Logres, attacking houses, killing people, rescuing girls like Narin?

Would you rather we hadn’t and left the poor child there?

Of course not, but that’s not the point.

It is, it’s the most important point, the protection of the weak and the freeing of captives.

Wasn’t there some bigger goal?

To slow the spreading evil, only God could stop it, but slowing it down meant more innocent souls being rescued; what else could they do?

Surely though, priests, monks shouldn’t and couldn’t condone killing, violence?

Yes, so long as the cause is just, the defence of the weak, resistance against evil is permitted, indeed required; so long as it is not for gain, it is righteous.

What did they want of her, what were those questions for?

We all must make our contribution to the good of all in our own ways; you have been given gifts, talents, that are needed and the time for them is near, it is His providence undoubtedly that you are here.

But my husband… He wouldn’t want us separated would He?

No, perhaps for a time if it serves His ends, but I am sure you will be restored to one another one day.

By now, they were on top of the bell tower looking over the eastern half of the island, just below the level of the walls of the fort on the slope above. Market gardens and orchards proliferated on the sheltered eastern side with a few gardeners, including monks, at work starting the planting of the Spring crops. To the north, near the edge of the island, was a graveyard surrounded by a drystone wall, containing low Celtic stone crosses.

He explained they were mainly the graves of monks, some Brothers at the Abbey in former times.

What about those in the far corner, they are bigger, laid out in an incomplete circle facing inwards, who are they?

Old non-clerical benefactors.

Why is the circle incomplete?

More may join them one day.

© 1642again 2018

Audio file