Besides excitement and trauma, might the shock of the new also provide a synapse re-ordering adrenaline burst that remodels the brain? As a little boy the make-believe near-future modernist world of Thunderbirds (and the like) had me goggle-eyed in front of the goggle box. On the other side of our front window, slums were being cleared for real-life Gerry Anderson marionette drama-style brutalist blocks. In the fullness of time, yes, a disappointment, but in the ‘then’ a thrill for a little boy. Adrenaline surged, the mind changed shape.

One is reminded of Ken, the playwright’s son who takes a position down a coal mine.

‘Oh, it’s not too bad, mum…’ says Ken, breathless, ‘we’re using some new tungsten carbide drills for the preliminary coal-face scouring operations.’

‘Oh, that sounds nice, dear…’ replies Mum, to which Dad barks in exasperation, ‘Tungsten carbide drills! What the bloody hell’s tungsten carbide drills?’

From the Monty Python sketch featuring Eric Idle as Ken and Graham Chapam as Dad, a point can be made. No matter how better the old days were, some will always prefer the thrill of the modern.

In the first class lounge at Euston Station, the minute hand touches ten and the little hand pokes towards three. Time to decamp from the middle-aged male heaven of a stool at a lino counter watching the railway departure board. Myself and Mrs AWS are on the right side of the Pashtoon manning the first class information desk who we were earlier able to address in his native language.

© Always Worth Saying 2025, Going Postal

As proof, he said he’d have some inside info for us just ahead of our three-thirty departure. Booked on the 14:38 which had been cancelled, we had no reservations north on a day disrupted by Storm Floris. With all but two trains cancelled beyond Preston, we’d have to stand for hours – or would we? He taps his nose and whispers, ‘Platform One’ – a full fifteen minutes ahead of any official announcement.

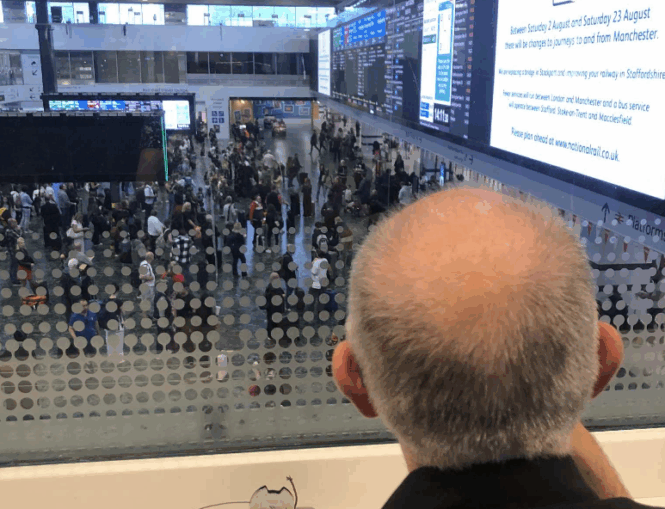

Sat in the lounge overlooking the concourse, we noticed an ebb and flow of people, as if pebbles jostled by an unwelcoming tide, when platform announcements were made. For the benefit of the uninitiated, such things are done at the last minute, resulting in a sudden movement of people jostling across the concourse heading for their train.

Number One is on the extreme right of the station next to the first class lounge but on a lower level. We made our way down the stairs and, without making it too obvious, snuck our way to the platform across the brutalist 60s concrete cube to be first in the queue at the ticker barrier.

Was it always so? Of course not. As per the neurological reasons noted, I think I’m the only person in the world who likes Euston as it is. Others prefer it as it was, or as it might be. The discerning reader must be allowed a history.

Euston first opened its doors in 1837 as the southern terminus of the London and Birmingham Railway, making it the first intercity railway station in the capital. At the time, the station was a monumental achievement and a symbol of the new industrial age, connecting the capital to the Midlands and later to the northern cities. The original station was modest in size but adorned with grandeur.

One of the most striking features of the original station was the Euston Arch, designed, as was the rest of the terminus by Philip Hardwick. This massive Doric propylaeum stood at the entrance to the station on Euston Grove. Made of Yorkshire stone and inspired by ancient Greek temples, it measured over 70 feet in height and 44 feet in width and symbolised the grandeur and permanence of the new railway age.

Euston Station on the London & Birmingham Railway,

Edward Radclyffe – Public domain

Behind the arch, a long, tree-lined drive led to the station buildings, which included a classical entrance hall and a pair of grand waiting rooms — one for ladies and another for gentlemen – with lavish furnishing and decorated with mirrors, chandeliers, and fireplaces.

The platforms themselves were below two train sheds with wrought iron and timber roofs, accommodating both arrivals and departures. The design was innovative for its time, combining elegance with functionality. The overall layout and architecture not only served the practical needs of railway operations but also impressed and reassured early passengers who may have been wary of this new form of travel.

Admired for its architectural sophistication and engineering foresight, Euston Station became a symbol of Victorian progress. Its original design embodied the confidence of a society on the brink of industrial transformation, offering a dignified and awe-inspiring beginning to journeys across Britain.

Interior of Great Hall at Euston Station,

Ben Brooksbank – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

‘Old Euston’ Arrival side,

Ben Brooksbank – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Just north of the original Euston Station lay one of the most unusual and fascinating features of early British railways: the rope-worked incline between Euston and Camden Town. This incline, about a mile in length, represented a compromise between contemporary engineering limits and an ambitious railway design.

The incline rose at about 1 in 75, a steep gradient for early locomotives. This posed a challenge to the steam engines of the time, which were not yet powerful enough to haul heavy trains up the slope from the low-lying Euston basin. To solve this problem, engineers devised an innovative system of stationary steam engines and a continuous rope to haul trains up the gradient. The rope attached to departing trains and wound around a drum powered by a pair of stationary steam engines housed in a purpose-built engine house at Camden Town.

The rope-worked incline remained in use for a near decade from 1837 to 1844 for passenger trains and for a while longer for freight. By the mid-1840s, advancing locomotive technology resulted in engines becoming powerful enough to climb the incline under their own steam. Over the decades, as the railway network expanded and traffic increased, Euston underwent several redevelopments. By the end of the Second World War, the station had suffered wear and damage. The post-war years saw a further decline in its condition.

This deterioration influenced the decision in the 1960s to demolish the original Victorian structures and replace them with the modernist station seen today — a decision that remains controversial given the loss of the iconic Euston Arch. This act provoked widespread public outrage and marked a turning point in Britain’s architectural preservation movement.

Euston station and Stephenson Square,

Hugh Llewelyn – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The new station, completed in 1968, featured a stark, utilitarian design typical of the era, prioritising function over form, and has been criticised for its lack of character. Architectural societies and conservationists such as John Betumen led efforts to save the arch but the preservation movement was still in its infancy and lacked the legal powers or public momentum it would later gain.

In 1961–1962, the arch was dismantled and demolished. Its stones were not stored — in fact, most of them were dumped into the River Lea near Stratford or used as fill in other locations. In a twist of history, in the early 1990s many of the original stones were rediscovered in the Lea. Since then, there have been campaigns to rebuild the Euston Arch in conjunction with the ongoing redevelopment of Euston Station for the High Speed 2 (HS2) rail project. The Euston Arch Trust, founded in 1996, continues to advocate for its reconstruction using surviving material and modern techniques.

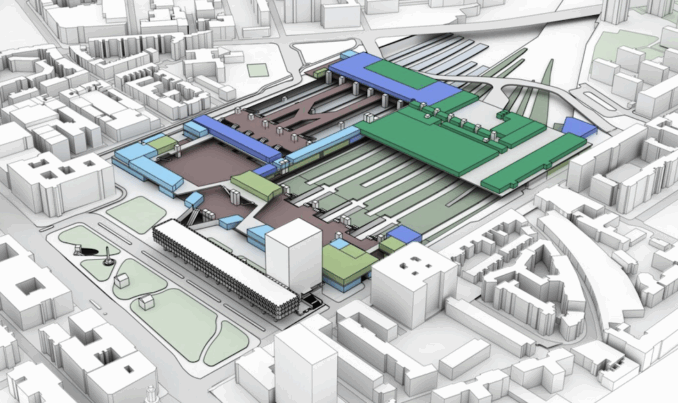

In recent years, Euston has once again become a focal point of transformation due to its role as the future London terminus of the HS2 line. This project is triggering extensive redevelopment aimed at modernising the station and surrounding area, with debates ongoing over design, costs, and environmental impact.

At first the early HS2 vision for Euston called for 11 new platforms, built in two phases: first to connect London to the Midlands, then later expanding for services to places in the North (eg Manchester/Leeds). The station would be built in three levels, with a 300m concourse, a dramatic roof letting in natural light, and extensive public space and retail. The platforms would be subsurface, each around 450m long, to accommodate long HS2 trains. There were also plans for improved connections to the Underground (Euston and Euston Square stations) to make interchanges easier, as well as new entrances on multiple sides and new public/green spaces north and south for cycle parking, etc.

Euston Station revised proposal,

Via Architects Journal – Fair use, illustrative, no alternative

However, a number of changes have been made, prompted by cost pressures, delays, and politics. Key changes include: In December 2024, the rail minister confirmed the new HS2 Euston station will now have only six platforms. This is a major reduction from earlier plans (which had up to 11 HS2 platforms). The scope of the station has been “rescoped” to reduce cost. The government remains committed to completing Phase 1 of HS2 (London/Birmingham), but the station design has been simplified to make it “affordable and deliverable.”

Some work paused in March 2023 due to inflationary pressures and to find more affordable design solutions. Cost estimates have increased. Concerns from the National Audit Office point out that the cost is rising well above earlier budgeted figures. Amidst headlines noting ‘Euston, we have a problem’, the existing buildings may well remain, with something similar – slab-sided and utilitarian – slapped next door for the HS2 platforms.

Although a rope worked incline will be out of the question, might the New Euston benefit from a Doric arch somewhere about it? Perhaps one containing stonework dredged from the Lea?

© Always Worth Saying 2025