The English constitution is often described as ‘unwritten,’ yet it has proved more durable than almost any codified rival. Its resilience does not stem from philosophical elegance or the vision of a single generation of lawgivers. Rather, it is the cumulative product of centuries of contested practice—an evolving settlement repeatedly tested, broken, and repaired in the heat of real political conflict.

Inherited Constraints and Hard Lessons

From the fifth century onwards, waves of armed elites—Anglo-Saxons, Danes, Normans—seized power in England. Each discovered that the country already possessed institutions such as shire courts, uniform taxation, and written land records that could not simply be swept away. Conquest was possible; wholesale replacement of the administrative order was not. Successful rulers learned to work through the existing machinery rather than against it, while unsuccessful ones were forcibly reminded of its limits.

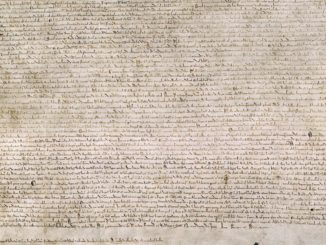

Magna Carta (1225), the Petition of Right (1628), the Bill of Rights (1689), and the great Reform Acts were never granted out of enlightenment. They were concessions extracted when one side had pushed too far and the other possessed both the means and the will to resist.

Judge-Made Law Over Academic Codes

While continental Europe embraced university-trained jurists who treated the prince as legibus solutus, England entrusted legal development to royal justices on circuit. Precedent, practicality, and the need to carry the shires mattered more than logical symmetry. Habeas corpus, trial by jury, and the principle that taxation requires consent emerged from adversarial encounters rather than abstract treatises.

Godfrey Kneller, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

• “The end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom… where there is no law, there is no freedom.” — John Locke, Second Treatise of Government (1689)

The Virtue of Incremental Reform

Continental constitutions have often been drafted in revolutionary moments and imposed wholesale. The English model grew incrementally—each major extension of liberty a specific bargain struck to defuse a specific crisis. Remedies were made ‘almost as fast as their diseases,’ grounded not in abstract theory but in the tested maxims of experience.

Joshua Reynolds, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

• “The House of Commons is the great security of English liberty… because it is chosen by the people, and feels with the people.” — Edmund Burke, Speech on the Duration of Parliaments (1780)

Exporting English Arrangements

Wherever English law and parliamentary institutions were carried by settlers with strong traditions of local self-government—North America, Australia, New Zealand, Canada—they took deep root and evolved into stable liberal democracies. In contrast, attempts to impose codified systems on colonies lacking such traditions often produced fragile republics and long periods of authoritarian rule. Even the admired American Constitution succeeded only because its drafters consciously grafted English common-law rights and habits of local jury government onto a new federal frame.

Antoine Claudet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

• “The English have exported their laws and their liberty to the ends of the earth… wherever an Englishman plants his foot, he carries with him the spirit of freedom.” — Thomas Babington Macaulay, History of England (1848)

A Warning from History

The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 remains a classic warning. When Parliament and Crown bypassed common-law courts with punitive poll taxes enforced by special commissions, ordinary freeholders saw it as alien tyranny. The result was the largest popular uprising before the Civil War. Though crushed, the poll tax was abandoned and the statute quietly allowed to lapse—another stress test passed.

Today, trial by jury is again under pressure, administrative penalties multiply, and voices call for ‘modernisation’ along inquisitorial lines. Each step is sold as efficiency. Yet the English constitution has no one-way ratchet. Abandon its principles, and liberty itself is at risk.

Thomas Erskine May, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

• “The moment you abandon the great principles of English law… you will find yourselves slaves.” — Lord Chancellor Erskine, House of Lords speech (1817)

Conclusion

English liberty was never designed in a seminar room. It was forged over a thousand years in the stubborn refusal to be governed without consent. Think on this long history—and be careful who you vote for.

But, what do you think?

© Roger Mellie 2025