“So how are things in Russia today?”

The taxi driver was a burly, working-class man in his 50s; I imagined a brickie now too old for the game. He thought briefly and mumbled a reply in which I caught the words spokoynyy and khorosho: “Things are quiet, it’s fine.” We were driving from the coach station to my lodgings for that first night, a hostel off Nevsky, the Oxford Street of St. Petersburg. That was indeed how the “capital of the north” looked — quiet and fine. They’d had a lot of tourists over the summer, he added, but not like me. Chinese, Indians. All gone now. It was early September, and the trees in the parks and avenues were still in full leaf.

Then he asked me if I had any small English coins to sell him — I thought I had misunderstood, but numismatics, it turned out, are a big deal in Putin’s Russia. No, I said, sorry. I didn’t try any more questions. I had little confidence in my very basic and now very rusty Russian; I needed to ease myself back into the language a bit first.

The hostel was not far, a “corpus” block inside a huge commercial complex. I spent half-an-hour trying to find the damned place — building 45 out of over 50, a drab block surrounded by, of all things, Central Asian vendors of women’s underwear. The hostel, to my relief, gave me a bottom bunk – I’m getting a bit old for tackling ladders at three in the morning on a loo run. It had been a long day, entailing a panic in Tallinn when I couldn’t find the coach station, anxiety when I thought I had booked the wrong coach, and a hairy three-hour wait at a border crossing I had not planned to use, during which I nearly had the euro third of my funds confiscated for breach of EU sanctions. I put my feet up, unscrewed a vodka and cranberry and drew the curtain on the world.

Back in Russia, for the first time in over 30 years. The last time, it was the early 1990s, when I crossed the length of it on the train from Beijing, using the “other” Transsiberian route. Then, we had passed through a land visibly on its knees, wracked by poverty and chaos, engulfed in humiliation and almost without uniformed authority. Quite a journey. And six years before that I had spent a springtime in Kiev, in the bleak, threadbare twilight of the Soviet Union. Hence the rudimentary Russian.

I had been planning this return trip for some years, but was thwarted by the Covid pandemic and immediately after that the war in Ukraine. The childish attempts to “cancel” Russia, by excluding it from football competitions, banning its concert violinists and censoring its news services, made me still more determined to somehow get there. This year, I decided I had waited long enough. Disregarding an HM government warning, I embarked on the ordeal of entering Russia overland, detailed in earlier pieces. These final segments focus on what I found.

Rather than bore you with a blow-by-blow account, I’m going to skip quickly over the what-I-did-on-my-holidays bit. I wasn’t really there as a sightseeing tourist. I wanted to know what Russia was really like, and what Russians today think about their government and their country, because these questions have been largely ignored in the western media. I wanted to talk to people, hopefully in English, but failing that, in broken Russian.

The actual details of the stay are pretty mundane anyway. The plan was spend a week in St. Petersburg and another week in Moscow, and leave via Kaliningrad if possible. I completed the first two “missions,” but not the third as I ran out of money (and nerve). In addition to stays in the two big cities, which, I was told, were “not the real Russia,” I went on day trips to three provincial towns. They were Vyborg, the capital of Russian Karelia, a now completely Russified and rather lovely old town set among the swampy forests near the Finnish border; Tosno, south of St. Petersburg, a nondescript industrial town with no obvious attractions, and Zelenograd, a place just outside Moscow that turned out to be not typically provincial at all, but a formerly forbidden city where the USSR had tried and failed to build a computer industry to rival America’s. I also walked about Ivangorod and passed through Kingisepp by the Baltic border. I did some of the sights — the Kremlin, the Winter Palace and loads of those lovely golden-domed Orthodox churches, but that’s not really what I had come for. I’d come for politics. So, let’s start with the sanctions, which were intended to cripple the Russian economy so badly the people would obligingly overthrow the government.

At the visible level, in the Russian “high street,” their impact has been close to zero. “It’s all just bullshit,” a clothes vendor who had lived for years in Texas told me. “Look around. McDonald’s has gone, but Burger King is still there, everywhere.” And so it proved: every big station had a Burger King. Other names like Starbucks had simply been revamped, in this case, to Stars. McDonald’s had not, which means Russia is finally rid of the world’s biggest offal vendor (and that’s a win in my book). In central Moscow, I found a few luxury fashion stores shuttered for “technical” reasons, one I think being Prada. But that was the only visible evidence of the sanctions. The shops were full, the supermarkets stocked Oreos, Nescafe and wine from half a dozen EU countries, and people went about their business much as they do anywhere else in Europe. I suppose all this sanctions-busting was being done through Turkey or Central Asia or simple import substitution. I saw no evidence of any kind of material shortage over those 12 days. The idea of Russians queuing for petrol is, in the heartlands at least, simply a lie.

Quiet and fine things may have been, but there were a few signs that the country is at war. If you used the Metro or went down any major avenue, you would soon see a big in-your-face army recruitment poster, offering a £50,000 upfront payment for enlistees. That sum would buy you a comfortable provincial flat outright. You also see a good few soldiers at bus and railway stations, probably on leave but still in uniform, and a few — I saw three in two weeks — with new artificial limbs. Overall, though, there was little sense of being in a war. The conflict seemed a very long way away, compartmentalised on the fringes of national life as the much less bloody Northern Ireland struggle was in Britain. You had the sense that Russia could keep up this fight for decades without much effort.

It took a week for these superficial impressions to be superseded by a more nuanced understanding of what was going on. The sanctions were having invisible effects as well, such as a shortage of components in railway and aviation maintenance, forcing the Russians to use substitute suppliers or simply do the job themselves. Tourism had of course been badly hit, but not as badly as you might imagine, as much of the slack had been taken up by visitors from outside the West. Nevertheless, talking to staff in hotels, I sensed frustration. And at an individual level, many Russians are disgruntled about their loss of access to Facebook, Youtube, Whatsapp and Instagram, though VPNs are very widely used to get round that. (I saw all of those apps being used in buses and trains (by discreet over-the-shoulder spying)). Also noticeably missing from Russian life now are Hollywood films and originals of western shows. Mama Mia was still on stage, but localised using Russian actors. TV had only a handful of imported shows.

Perhaps the most important loss for the ambitious young is access to western job markets. Many Russians worked abroad and they still want to. I was questioned by a building maintenance guy in his early 20s who wanted to make his fortune in London. (It’s not quite impossible for Russians to go to the West now; it’s just much more difficult, with applications for the Schengen visa taking months to process.).

So overall, the economy is still just about ticking over, despite the best efforts of the most powerful group of nations on earth. But life has undoubtedly got harder since 2022. Though Russia is largely self-sufficient in basics, the 40% drop in the value of the ruble has inevitably had some effect. Wages have declined, and inflation is quite high, though it is hard to say how much of that is due to the global surge in prices after Covid.

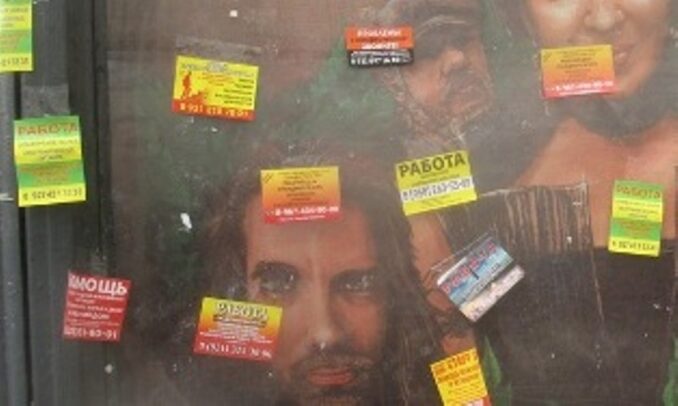

The problem I did not expect to find is the chronic labour shortage, affecting all of the economy. I’ve never seen the like. You saw stickers on almost every lamppost and billboard in Moscow and St. Petersburg, with a number and the words “rabota” (job), and “trebuetsya” or “pomoshch,” both meaning “help needed.” (Rabota, by the way, is the Slavic word giving us “robot,” work (machine)), via Czech.

A number of factors are at play. In addition to the war, which has soaked up military and industrial manpower and driven many people out of the country, and the effects of trade disruption, a government crackdown on unregistered migrants has resulted in many going back to their homelands. Contrary to a popular misconception, Russia has plenty of migrants: 5 to 10 million, mostly from the Central Asian former Soviet republics, and a large number of them illegal. You see them everywhere, though Moscow is nothing like London or Paris (and hopefully never will be). Nonetheless, Russia is and long has been the most multiracial of all the former Eastern Bloc countries.

Another factor is people simply opting out of the workforce, because pay is too low. A hotel receptionist said that it now makes more economic sense to register as a student (universities are free and you can get cheap accommodation) than take a job. Finally, there are the overarching problems and obvious long-term consequences of Russia’s very low birth-rate.

Having said all that, you do not really notice a lack of workers on the street; on the contrary, there are still plenty of people paid to pointlessly guard doors and stare at X-ray machines at Metro entrances. Nothing was cancelled or disrupted due to lack of staff during my stay.

The situation was little different in the provincial towns I visited, Tosno, Vyborg and Zelenograd. None of them had the metropolitan attractions of the two big cities, of course, but they weren’t cesspits of poverty and neglect either. They all had adequate if sometimes shabby apartment blocks, busy roads (about a quarter of cars are Chinese now, and I doubt that the western automakers vacating the market will ever get back into it), properly functioning infrastructure and fully-stocked supermarkets. Vyborg, a castle town, was lovely.

The place you perhaps do see signs of real want is the deep countryside. This has long been the case and has more to do with geography than politics. The last time I took the St. Petersburg-Moscow train, years ago, it was night, so I had not really “seen” this, the most populous part of Russia. I had visions of wooden cottages, fruitful orchards and pretty maids with baskets, with that delightful rustic palisade fencing all around to keep the bears off. In reality, what you find along almost all of the 700 km between the two cities is flat, swampy forest. I did not notice more than a handful of farms the whole way. Hamlets are divided by huge distances, and you pass through or by just two cities, Tver and Novgorod.

I knew that Siberia was a wilderness, but I had not realised that the populated north-western corner is close to being one too. Russia’s best farmland is in the south (the breadbasket of the USSR was the Ukraine and Belarus). Here, though, the pine forest extends pretty much from the Baltic coast of Poland and the Baltics deep inland to the Urals. Of course, it is not continuous; there are many open spaces and clearings, but nonetheless, wherever you are, the horizon will always be forest, and always flat and dotted with pools of stagnant water, marshland and creeks. At these northern latitudes, the winter is too long and the soil is too poor for clearance and cultivation to make sense. The result is rural isolation and poverty. Villages usually had a couple of abandoned cottages with the roof falling in. These conditions also plague Estonia and Latvia, of course, accounting for their thinness of population too, but the Baltic states look much less dilapidated, thanks to heavy infusions of EU CAP-enabled funding.

In sum, the economic situation in Russia is not great but not critical either, and, as said, I think they could go on prosecuting the war for years to come. One aspect of the sanctions was refreshing to me, even if probably not to most Russians: being out of the suffocating American cultural embrace for once, and in a purely European environment. Teremok-chain blini and mushroom soup made a much better street meal than a Big Mac.

Next up: the political stuff, including the questions of Russians really think of Putin, how free are elections, and how repressive the climate now is.

© text & images Joe Slater 2025