My great-grandfather on my father’s mother’s side served in Afghanistan. Being hill, mountain and lake types, our local regiment, The Border Regiment, deployed to the disputed territory between that country and British India in the late 1800s.

The Great Game

During the 19th century, British interest in the region revolved around strategic concerns related to the geopolitical rivalry with Russia, immortalised as the “Great Game”. We viewed Afghanistan as a critical buffer state that could prevent Russian expansion towards India, the jewel in the crown of the Empire. To secure this frontier, Britain sought to control Afghanistan’s foreign policy and supported rulers who aligned with British interests. This led to two major military interventions: the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842), which ended in a disastrous rout, and a second conflict between 1878–1880.

Remnants of an Army,

Elizabeth Thompson – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

It was during the 1842 retreat from Kabul that only one British soldier, Dr William Brydon, survived from a force of 16,000. The others, scattered into small groups, perished during ambushes and attacks from Afghans. It is said the enemy permitted Brydon’s escape only to allow the cautionary tale to be spread when he reached safety. It is also said that upon arrival in Jalalabad and being asked of the Army, Brydon replied, ‘I am the Army.’

Following the more successful engagement between 1878–1880, Britain gained control over Afghanistan’s external affairs through the Treaty of Gandamak. Although Afghanistan remained autonomous, British involvement then, and throughout the rest of the century, reflected a desire to maintain dominance in the region and to keep Russian influence at bay.

By the 1890s, the British Army in Afghanistan was involved in securing the north-western frontier of British India and managing tensions along the Afghan border, in the context of that ongoing Anglo-Russian rivalry – although Afghanistan remained independent under Emir Abdur Rahman Khan.

The post-Second Afghan War settlement

During this period, British military activity concentrated not within the heart of the country but along the border, through the establishment and reinforcement of outposts and fortifications in the tribal areas bordering Afghanistan.

We also supported Emir Khan by supplying funds and arms to help maintain internal control and resist Russian influence. The British were also involved in the Durand Line Agreement of 1893, which defined the border with British India — an act that required military presence to enforce and monitor the new line.

Thus, while the Army was not engaged in full-scale warfare within Afghanistan during the 1890s, it played a critical role in frontier defence, intelligence gathering, and the broader imperial strategy to contain Russian expansion.

Emir Abd or-Rahman, Rawalpindi, April, 1885,

Unknown photographer – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

The Durand Line is named after Sir Mortimer Durand, the diplomat who negotiated the agreement with Emir Khan. Its primary purpose was to define the limits of British and Afghan spheres of influence and to create a clear frontier that could help manage tensions and prevent Russian encroachment into British-controlled territory.

The line stretches for about 1,640 miles and cuts through Pashtun tribal areas, dividing ethnic and cultural communities between the two sides. While we considered the Durand Line a formal and binding international border, Afghan leaders and much of the population viewed it as an artificial and imposed boundary, as it divided related tribes.

After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the Durand Line became the border between Afghanistan and the new state, but Afghanistan refuses to recognise it as a legitimate international boundary. The line remains a source of political tension and conflict to this day, symbolising the historic legacy of unresolved, and unresolvable, territorial disputes in the region.

Troublesome Waziristan

As for my great-grandfather, his India Service Medal bears the clasp Waziristan 1894–1895. This campaign was part of the ongoing efforts by the Raj to control the unruly tribal areas along the North-West Frontier of India – particularly the regions inhabited by the fierce and independent Pashtun tribes such as the Wazirs and Mahsuds.

This specific campaign arose as a response to tribal resistance against British authority and incursions into British-held territory. The Waziristan region, lying along the border with Afghanistan and about 150 miles due south of Kabul, was a strategic but volatile area. Our forces often found themselves engaged in punitive expeditions to assert the Crown’s influence.

In late 1894, tensions escalated when the Wazir tribes, particularly the Mahsuds and Darwesh Khel Wazirs, began launching raids into British-controlled territory, attacking military outposts and supply lines. These acts of defiance prompted the launching of a large-scale military expedition into Waziristan in late 1894, which continued into early 1895.

The campaign was commanded by General Sir William Lockhart, who led the Tochi Field Force, a column of several thousand troops comprising British and Indian regiments and my great-grantfather. The objectives of the campaign were to punish the rebellious tribes, destroy their strongholds, and reassert authority in the region.

The campaign involved difficult mountain warfare in harsh winter conditions, with British forces facing stiff resistance from tribal fighters well-versed in guerrilla tactics. The terrain was rugged and unfamiliar to many troops, and logistical difficulties compounded the challenges.

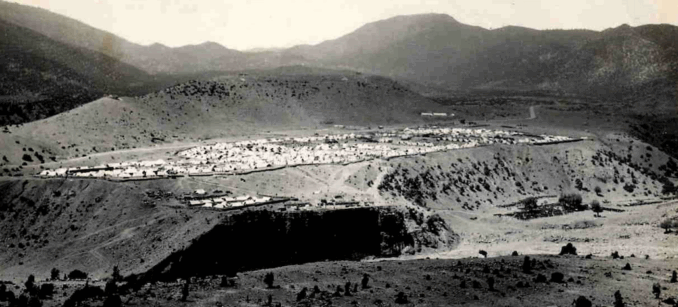

Razani Camp, August 1938, in North Waziristan, from the south east,

Brian Harrington Spier – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Nevertheless, Lockhart succeeded in reaching key tribal centres, occupying villages and confiscating livestock to break the economic backbone of the resistance. Despite the military success in terms of inflicting damage and compelling temporary submission from some tribal leaders, the campaign did not result in long-term pacification.

Beyond the movement of the great tectonic plates in the world of diplomacy, on the human level The Cumberland and Westmorland Advertiser of the 26th February 1895 reported a lucky escape:

‘As the 1st Brigade were marching from Kanigarum to Jangal the rear and baggage guards were fired into and Private T Harris, a Carlisle man, was wounded. He had a narrow escape, his mess-tin being the means of saving his life. The bullet had been fired from a height, and struck the top of the tin. One half of the bullet penetrated through and entered the man’s back, inflicting a severe though not a dangerous wound, and Harris is now doing well.’

However, as a reminder of the eternal mixed fortunes of war the piece continues, ‘Dr Sullivan, who was with the brigade, was found one morning dead in his tent. Although 15 others slept in the tent, nothing was known of his death until the morning.’

Over a century and a quarter on, one of the most popular exhibits in Carlisle Castle’s Museum of Military Life is ahelmet from the modern-day conflict in Afghanistan – with a bullet hole in it. As with Harris, the wearer survived.

Back in 1895, British forces began withdrawing from Waziristan, having declared the operation a success. However, like many such frontier expeditions, it achieved only a temporary lull in hostilities. The tribal areas remained restive (and do to this day), and British forces would return over the following decades. The 1894–1895 Waziristan campaign was a typical example of the “butcher and bolt” policy employed on the frontier — short, sharp punitive expeditions meant to punish and deter rather than occupy and administer.

In essence, the British campaign in Waziristan in 1894–1895 highlighted both the strategic importance and the intractable nature of the tribal frontier. It showcased the limitations of imperial military power in dealing with decentralised tribal societies and foreshadowed the continuous unrest that would define the region for generations.

The latest rouse of which is the anti-British madness of the secret dumping of tens of thousands of Afghans onto unsuspecting British towns.

© Always Worth Saying 2025