‘The Shortest History of England’ by James Hawes is not too short and tops the scales at 272 pages. A bright chap, the 64-year-old writer graduated in German from Hertford College, Oxford, and studied for a PhD in Nietzsche and German Literature between 1900 and 1914 at University College, London. A published author in both fiction, non-fiction and screenplay, Hawes’ 1997 film adaption of his own best seller ‘Rancid Aluminium’ is held to be one of the worst films ever made.

Reviewers complained of a fine cast wasted (Rhys Ifans, Joseph Fiennes, Sadie Frost, Steven Berkoff, Keith Allen, Dani Bher and more) and an unintelligible storyline sinking to the level of a boring and un-funny vodka advert parody. Judging from the name and the critics’ references to voddy, it had something to do with Russian gangsters laundering dirty commodity loot through the City of London.

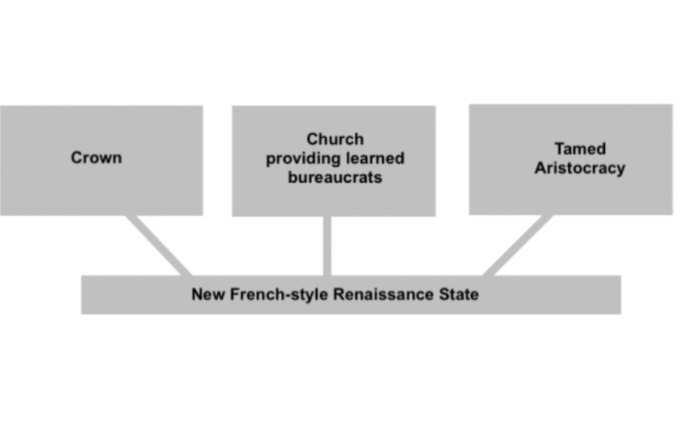

Hawes is on firmer ground with ‘The Shortest History’, which is written with clarity, is persuasive and benefits from handy maps, reproductions of old prints and one or two small black and white newspaper-type photos. Imagine a ‘Loads of Interesting Things About England’s History’ compendium made up of 1950s cuttings and put together in continuous prose by AI after being instructed to write like John Alldridge. That’s the kind of thing. Having learned his lesson the hard way in Holywood, Hawes uses pie charts, Venn diagrams, arrows and circles (not easy to do in a gangster film and in Russian) to explain difficult concepts with refreshing clarity. For example:

© Always Worth Saying 2024, Going Postal

As per convention, the author begins at 55BC with Caesar eyeing a mysterious land beyond Europe peopled by those the Greeks called Pretaniki or Bretaniki. Famous as a source of tin and copper (valuable in the production of brass and bronze), upon closer inspection the Romans discovered the coastal southeastern tip of the islands to be inhabited by Belgic Gauls. These were settled raiders from the country of Belgae, modern-day Belgium. As corroboration, recent archaeology has unearthed a distinctive Aylesford-Swarling/Atrebatic culture in the right place and dated to the correct time. Inland lived an older, longer-established population.

Although Caesar withdrew, across the following decades trade and contact grew. In 25 BC, Greek writer Strabo described Britannia – or at least its southern coast – as a virtual Roman property. In 43 AD, Emporer Claudius invaded properly, but for the purpose of taxation he was only interested in the tribes advanced enough to use coins. Here Hawes introduces a divide which continues in importance throughout the book and, therefore, throughout the history of our country.

The coin-bearing peoples lived in the more prosperous part of a divided land. The divide being a Jurrasic split along the rivers Humber and Trent which continued as a diagonal to the Severn. Even today, we think of this as the North/South divide. South of the Jurrasic geological line are young sandstones, clays and chalk. Above it lie older shales and igneous rocks. The result is summarised by Hawes as: ‘Geology, geography and climate conspire timelessly in favour of the South-East’. In one of his helpful graphics, the author shows:

Better soil geology + better climate for agriculture + better links to the continent = South-East of Britain is richest.

This, more or less, becomes the backbone of his book and runs through the chapters as if a river running between limestone moors covered with scruffy sheep and lush pasture covered in fattening cows. By 100 AD, the South-East appeared a contented, prosperous colony. Tacitus observed those to the south to be related to the Gauls. Those north (of the Trent) were Germanic, and those to the west were like the Iberians. Quoting Trevelyan;

‘It was in the fruitful plains of the South-East that the Latinized Britons were concentrated, in a peaceful and civilian land, where the site of a cohort on the march was a rarity, where Roman cities and villas were plentiful and Roman civilisation powerful in its attraction.’

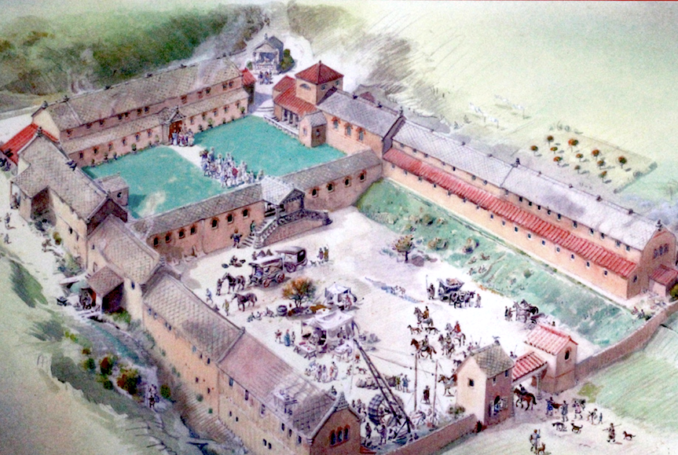

Depiction of Chedworth Roman Villa, late 4th century.,

Robyn Cox – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

At this point, another important and long-lasting faultline emerges. Just because someone rules part of the British Isles, does that mean they can or should rule all of it? Assuming that to be one of those schoolboy Latin questions expecting the answer yes, the Romans struck out from their souhern hinterland but failed. Scotland remained unconquered and had to be confined to the other side of Hadrian’s Wall. Wales and the North of England ‘were only ever ruled and taxed at spear point.’

An accompanying map shows numerous roads and Roman villas south of the Trent but fewer to its north, and then only following the main routes towards Chester and York. North of that are roads but no villas. As I type, I sit to the northwest of the cavalry fort of Petriana, less than a Roman mile north of Hadrian’s Wall. The fort protected the western part of the wall and the garrison outpost of Luguvalium (today’s Carlisle). I can confirm there isn’t, and apparently never has been, a Roman villa in sight.

In the other direction, the English Channel didn’t cut the south of Britain off from the rest of the Roman Empire, but provided a vital link, it oft being easier to travel by land than by sea. In 359 AD, 800 grain ships travelling from there relieved the starving Rhineland. But, about the same time, those routes came under threat from the Saxons.

Roman rule faltered as legions withdrew to fight other Romans. At the start of the fifth century, the Roman armies left for the final time. Amidst the vacuum, southern Britons found themselves assaulted by barbarians, Scots and Irish came from the North-West (in coracles) and Picts from the north. In the middle of the fifth century, according to Hawes, what happened next was no Anglo-Saxon invasion. Rather a plea for help from King Vortigern, of the Romano-British civilisation south of the Trent, to the Germanic Saxons of northwestern Germany and the Germanic Angles of the southern part of the Danish Peninsular.

Minstrel singing of the famous deeds of heroes,

Joseph Ratcliffe Skelton – Public domain

Elsewhere in Europe, something similar occurred. Germanics, who for the most part staffed the late Roman army, were on the move in what every German schoolboy learns of as the ‘Migrations of The Peoples.’ However, in other parts of the continent, self-sustaining war bands migrated and assimilated into the local culture.

Whereas here, a sea-road from northern Germany and southern Denmark allowed entire tribes to migrate and replace the culture they found in southern England. A state of affairs which Hawes describes as England’s ‘founding uniqueness’ and explains why, 15 centuries later, an Englishman can’t make out poetry in Welsh but can (just about) understand a German shouting at his dog.

Fascinating stuff and well worth a read. ‘The Shortest History of England’ by James Hawes is available for £8.99 in bookshops, and from Amazon at about the same price, depending on postage and packing.

© Always Worth Saying 2024