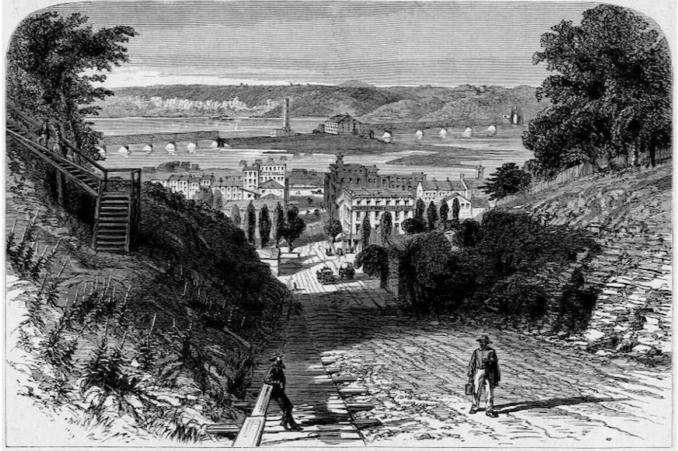

Dubuque, Iowa

Bridges on the Mississippi, at Dubuque,

D. Appleton & Company – Public domain

The first thing you learn about the Middle West is the bigness of it. You could, for example, sink without trace the whole of Switzerland in Lake Michigan.

The Illinois River at Peoria is wider than the Danube at Budapest. Some parts of it are so flat that a railway once laid 100 miles of track without having to level off an inch of soil.

That is one way of looking at the bigness of it. Another way is to go a day’s journey through it.

I arrived in Chicago from the South with only one thought — to relax for an hour or two between trains before pushing off North-West, into Iowa. Then I remembered that somewhere in these parts lived an old friend whom I hadn’t seen since the war years in Italy.

I traced her through Telephone Information.

And so there I was in a public call box in a railway waiting room speaking to someone whom I judged to be well over 100 miles away. As I saw it, this was only to be a “hail-and-farewell” affair.

After the preliminaries the conversation settled down into what was practically a monologue. Something like this:

“Now look here. This is what you do. You take the South Shore Electric to South Bend. That’s only 60 miles. You’ll do it in two hours. I’ll meet you there in the car. We’ll be home in time for dinner. You can stay overnight and either my husband or I can run you back in plenty of time to catch the train into Chi.”

So much for my rest period between trains. Instead, there was I racing east through the cold, clear morning with a hard frost riming the windows. And there was my hostess dropping everything and driving casually 50 miles south to meet me.

That was not the end of it. Somewhere between Sturgis, Michigan, and South Bend, Indiana, she recalled that a college group in North Manchester was rehearsing a play of mine that night. And so there we were, after a delicious, thought-provoking supper of steak and salad and French-fried potatoes washed down with a good Californian claret, rushing off 120 miles into the night (in a car that was only happy when it was touching 70) over a broad, arrow-straight highway. By that time I was past all protest.

“You’ll love it. And so will the kids. They’ll be tickled to death.” And as an afterthought, “We’ll have dessert when we get back.”

And I did. And they were. And we did have our dessert when we got back. The national dessert — a bowl of strawberry and vanilla ice cream. And in my honour tea “made the English way.”

While time obligingly stood still, and my host, whose father came from Nottingham and who learned to play cricket in Boston, Mass., discussed with the true enthusiasm of the amateur a new theory of organic gardening pioneered by an Englishman in Derbyshire.

And so a day which had begun over a breakfast of smoked farmhouse ham in a dining car rocketing through still-sleeping Illinois ended with ice cream and tea in Michigan.

I suppose it is this very bigness of the Middle West which makes the Middle-Westerner think largely in superlatives.

There are apparently no villages in the Middle-West — at least if there are I never saw one. Half a dozen houses, a church and a filling station is designated a town. Anything bigger becomes automatically a city. And road-signs, placed strategically just before and just after you pass through, boast proudly the name, population (at last census), and altitude of this latest “city.”

To the stranger they may all look exactly alike. All seem to have length without breadth.

The same straggling main street fringed by the same hotch-potch of clapboard and stucco and neon. The same service stations with the attendants in the same uniforms.

In each you see an identical set of people: the same teenagers going off to school in sweaters and blue jeans; the same farmers in plaid wind-breaker jackets and fur caps with ear-muffs; the same housewives, bulky and purposeful.

Yet on closer examination you will find that each thriving community has something peculiar and particular to boast about. It may only be the biggest saw-mill in the county. But for all that, it is the biggest. It is the beginning of bigger and better things.

You understand, too, why the “skyscraper” was invented in Chicago. Some people, I know, find this typical Middle-West love of the superlative for its own sake irritating.

Many Americans find it acutely embarrassing (although one of them, Sinclair Lewis, became famous on the strength of it. And I suppose it is again typical of the Middle West that the town which he satirises so drastically — Sauk Centre, Minnesota — now cherishes above all things the original manuscript version of “Main Street “).

To the visitor from an old-established country like Britain there is something brave and exciting about this brash mushrooming world. It is so easy to poke fun at the man who calls his one-room shop a “department store” and the boy who tacks a sign “television consultant ” on the shed at the bottom of the garden.

In the Middle West it is still possible to dream dreams. And the man in the shop is remembering Gordon Selfridge and Marshall Field. And the boy in the shed is thinking of Henry Ford. All of whom were from the small-town Middle West.

And never forgot it.

Another thing you quickly discover about the Middle West is its very “middleness.” If the Average American exists you’ll find him somewhere in the nine great states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Nebraska, and Kansas.

You’ll probably discover him in a small town with a population of 50,000 and a name like Peculiar, Missouri; What Cheer, Iowa; or Kalamazoo, Michigan.

On closer examination you would no doubt find that he had an Irish father and a German mother and is married to a girl who was born in the same small town but still talks about Sweden as the “Old Country.”

By persuasion he is a Baptist. He is a member of the Kiwanis, the Lions, and the local Rotary. His daughter is in her third year at Senior High School, and he is training his son to follow him into the family business.

Because of his emigrant background and the stories his grandparents used to tell, he is vaguely opposed to anything European. Though a great roamer — he takes his vacations either in Canada or Mexico — he had never been outside his own country before the Army called him up. He will probably retire before he is sixty and settle down in California.

His name could be Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, or Paul Hoffmann. Or he could be William Kraus, who is a cashier in the American Trust and Saving Bank here in Dubuque.

In our short acquaintance Bill Kraus taught me a lot about the Middle West. He told me, for instance, how when he was a small boy the Irish and German communities used to keep very much to themselves at opposite ends of the town. But all that is changing. Bill married a girl from the “Irish” end of town.

“We don’t talk much about the Old Country nowadays,” he explains. “I guess we’re all just plain Americans now.”

And here’s another significant trait about the Middle-Westerner. Though Bill works hard in the bank all day he isn’t ashamed to serve behind the bar most nights though he isn’t a drinking man. The reason? “We need the money.”

When you read about Americans living on the fat of the land and throwing ‘their money about like drunken sailors’ remember Bill Kraus.

Dubuque is a hard-working little town, perpetually in its shirt-sleeves, fortunate in its position on the north bank of the Mississippi, which is getting on for half a mile wide here.

It is a lumber town primarily. Its largest manufacturer occupies 21 acres of floor space; and here they make window-frames, roll-up garage doors, and plastic accessories of all kinds.

It has its local genius: a young man who thought up an idea for a toy tractor, sold the idea to a Chicago store for $100,000, and now operates a ten-million-dollar business as a toy broker.

It also has one of the best systems of local education I’ve seen, which takes care of a youngster’s schooling, free of charge, from the age of five until he’s 19. And since it’s part of the American way of life, if a boy wants what we like to call Further Education and his parents need him as a wage-earner he will cheerfully find a compromise.

A local hero, the captain of the college basket-ball team, told me, proudly, how he and a small syndicate ran the best newspaper stand in town.

Dubuque is old, too, as Middle-West towns count age: its first church — the oldest in the state, by the way — came into being one day in 1833 when an itinerant preacher forded the Mississippi from Illinois and preached the first sermon in Iowa on the other side.

And perhaps — because in those early frontier settlements the church arrived in the first covered wagon — this explains the important role which the church still plays in the life of the community.

Eighty per cent of the people of Dubuque belong to one church or another, I was told. Nearly 50 per cent come to church on Sunday. Congregations of 1,000 in some of the larger churches are commonplace.

The range of church activities open to members is quite remarkable. The Church Room seems to be buzzing with busy life every night in the week – with Church Suppers, Couple’s Nights; and Daughters’ and Dad’s Dinners.

I was asked to speak at the Men’s Club of St `Luke’s Methodist Church. I found myself talking about Britain to an audience of 60 – all solid men of business, among them the Superintendent of Schools, the principal of the High School, several doctors, a dentist, and the owner of the largest mill in the town.

The next night the hall was booked for the Women’s Society. A hundred and forty of them had already paid 50 cents (about 3s. 6d.) so that they could listen to a literary appreciation of a new novel called “The Dark Hour.”

I was warned before I left New York that I would find the Middle

West bluntly anti-British. Unless almost everyone I have met so far has been politely hiding his feelings on my account that has not been my experience.

The only anti-British sentiments I have heard — and they were made honestly and openly in my hearing — came from a large square man well on in life who might have posed for old John Bull himself.

“I’ve never had much time for the British since they threw Winston Churchill overboard after the war,” he opined. And I had to listen to a long catalogue of sins committed by the British in the name of democracy since 1945.

Much of his information was wildly inaccurate (how hard it is to explain to Americans that we don’t “own” Canada and Australia!). But he had the bit between his teeth and refused to be comforted.

Oddly enough, by blood he was as British as I am. He was born in Cornwall. And he sounded exactly like my grandfather, who could never understand what the Almighty was at when invented Frenchmen…

But in that same audience there was a young chemist who had been wounded in Normandy on D-Day, who said, “Forget the bird-brains, pal. You don’t have to come three thousand miles to tell there’ll always be an England. We know that already.”

And there was a manufacturer who has been waiting three months for a delivery of spare parts from Coventry. He could have cancelled his order and placed it in Detroit, but he was prepared to wait a little longer because he still had faith in British workmanship.

And I thought of the young man I had met in the Fourth Grade of Marshal Elementary School that afternoon: a young man nearing his eighth birthday who was brought forward, blushing furiously, to tell me how, quite unprompted, he had sat down at his desk and written a letter of sympathy to “Queen Elizabeth, Buckingham Palace, England.’

This article first appeared in the Manchester Evening News on 12 March 1952

© 2024 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2024