Railway Construction

Initially, the railway construction schedule allowed reasonable working conditions to be imposed on the POWs who, at that time, formed the majority of the skilled workforce. This combined with the fact that the work was being done during the dry season of 1942-43 meant that few deaths occurred during the first eight months of the construction period.

Deaths: July 1942 to February 1943

Americans: 0, Australians: 27, Dutch: 136, British: 2

In March 1943 when the Japanese High Command ordered a more rapid completion of the railway, soon to be known as “The Speedo”, working conditions became much worse. Bigger work quotas, longer working hours and increasing brutality were the norm. The inadequate diet, which had just about been sustaining the prisoners no longer proved sufficient and their physical condition began to deteriorate. But still the death rate remained moderately low:

Deaths: March 1943 to May 1943

Americans: 4, Australians: 148, Dutch: 418, British: 430

The arrival of the wet season of 1943 saw the real tragedy of the Thailand-Burma railway construction because disease thrived in the tropical heat and the effect on men already weakened by meagre, unsuitable rations and brutal work was devastating. They fell victim to illnesses that would not usually prove fatal if reasonable accommodation, adequate food and medicines and time to recuperate had been provided by the Japanese.

The two sections of the line finally met near Konkoita towards the end of October 1943 and the completed line was operational by December 1943.

Deaths: June 1943 to October 1943

Americans: 88, Australians: 1,630, Dutch: 1,303, British: 4,283

By early 1944 almost all Allied POWs had been evacuated from the jungle camps to base camps and hospitals around Kanchanaburi. The fit survivors of the ill-fated ‘F’ and ‘H’ Forces were quickly transported back to Singapore whilst their desperately sick comrades remained in two hospital camps in Kanchanaburi. Of this group, a further 550 were to die from the effects of their terrible ordeal on the railway.

Throughout 1944 the Japanese shipped many of the fittest POWs to Japan – to work in mines, shipyards, factories and foundries. As always, the Japanese refused to identify the ships carrying these prisoners and many of the men died when the ships they were being transported on were sunk by Allied submarines or planes. For most of those who remained in Thailand conditions did improve compared to the railway construction period. Better food, less work and a much-reduced threat of disease meant that the death rate dropped dramatically and men regained a degree of reasonable health.

From February 1944 to August 1945 the number of deaths was;

Americans 5, Australians 113, British 440, Dutch 451.

Approximately 200 were killed during Allied bombing raids along the railway.

The End Of WWII

From time to time work parties were assembled and taken back to the railway to cut firewood, repair damage or prepare defensive positions for the expected Allied attack against Thailand. Conditions for these groups would soon deteriorate to become as bad as those experienced during the initial construction of the railway. In May 1945, 1,000 men were taken from Nakhon Pathom Camp, to build a road from Prachup Khirikan to Mergui. 235 died during the construction.

Many of the Asian labourers were evacuated to base camps around Kanchanaburi but unlike the Allied prisoners of war very little was done for them and many thousands more died before the end of the war – 5,000 in one camp alone.

To many prisoners the end of the war did not come as a great surprise. Numerous groups within the railway workforce had been following the progress of world events by getting information from secret hand-made radios they’d constructed using parts stolen from the Japanese. The local population was another source of news. Information was passed to the POWs in the form of notes dropped close to work parties or hidden in baskets of supplies delivered to camps. Words would be whispered as people passed one another or old newspapers being used to wrap supplies.

What was surprising and of great relief was the sudden, unexpected Japanese surrender following the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bomings. This was not just an end to years of purgatory but also a narrow escape from certain death. Japanese High Command had issued orders that all captives were to be killed in the event of Allied landings in the areas where POWs were held. This order was carried out in the Philippines and in Borneo but not in Thailand or Burma even though some Japanese camp commanders forced the POWs to dig large grave pits in readiness for their forthcoming execution.

After the War

For the POWs in Thailand it was to be several weeks after the Japanese surrender before real freedom came. Due to the suddenness of the Japanese surrender it took time for the Allies to move men and equipment into the areas where prisoners were held. During this period food and medical supplies were parachuted into many of the camps.

When the defeat of Japan became inevitable plans were developed to recover and repatriate POWs from the many camps throughout Asia. This task was entrusted to a group formed in early 1945 – RAPWI (Repatriation of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees).

At the time of the Japanese surrender there were tens of thousands of Asians still forcibly employed on operating and maintaining the railway. It was quickly realised by the Allied officers still encamped in Kanchanaburi that unless they took over control of the railway, many of the labourers would abandon their workstations and force the closure of the entire network.

This closure would jeopardise the recovery not just of the several hundred POWs still on the railway but also the feeding and eventual recovery of more than 50,000 Asians so with the assistance of American and British undercover organisations already in place in Thailand the repatriation went ahead quickly and smoothly. By the end of September 1945 more than 50,000 American, Australian and British former POWs were on their way home.

Unfortunately, because of the political situation that emerged in the Netherlands East

Indies after the surrender of the Japanese, 30,000 Dutch former POWs and civilians remained in camps until as late as 1947. Many of those freed from camps in Java were transported to Thailand to join their husbands or fathers.

Search For The Dead

As the newly-released POWs were being repatriated through Bangkok or Singapore they were debriefed and any death records they held were collected. Early in September 1945 members of the Australian, British and Dutch Army Graves Services assembled in Bangkok and took over the records collected and collated by the ex-POW Headquarters. Thirteen former POWs volunteered to remain in Thailand to assist with the search for the thousands of graves scattered along the length of the railway and the work camps.

A diary of the subsequent search was written by one of these dedicated men, a British Army Padre, Henry Babb. This diary makes moving reading as Chaplain Babb described the search in great detail, his memories of his own captivity and the behaviour of the now quiescent and obedient Japanese.

This search commenced at Thanbyuzayat on 24th September 1945 and concluded at Nakhon Pathom on 10th October with the recording of 10,549 graves, in 144 cemeteries on or near the railway. The search party failed to locate only 52 of the graves they were searching for.

One sad legacy of the railway is that not one single Asian labourer was buried in an identifiable grave, and that only three may ever have been exhumed and reburied and then only as unknowns.

The Human Cost

One of the few Geneva Conventions that the Japanese actually decided to obey was the obligation placed on combatant nations during a time of war to maintain records of enemy captives. The prisoners themselves were involved in this record keeping and would often bury copies of their records in newly-dug graves hoping they’d eventually be retrieved and become important documents. After the war both Japanese and POW records were used to compile accurate figures of total deaths.

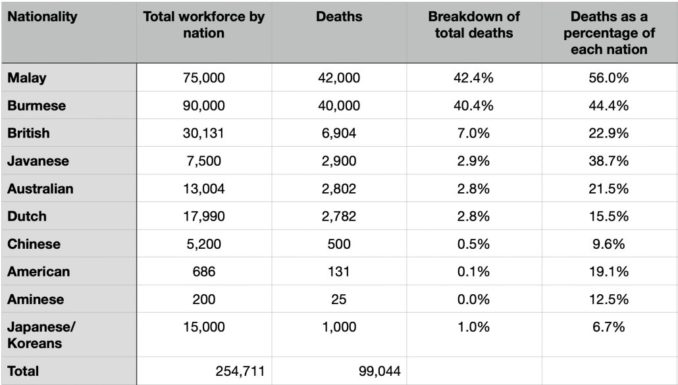

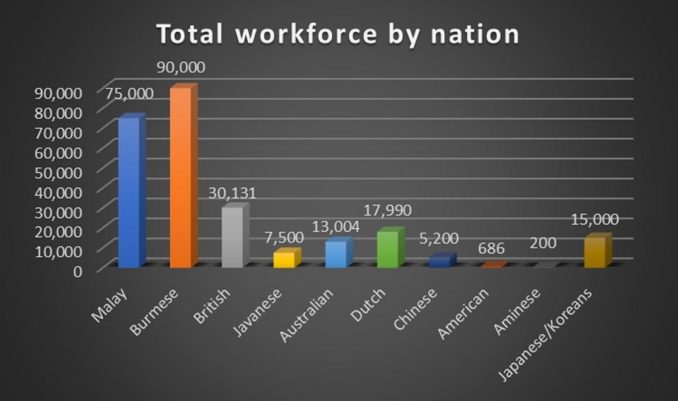

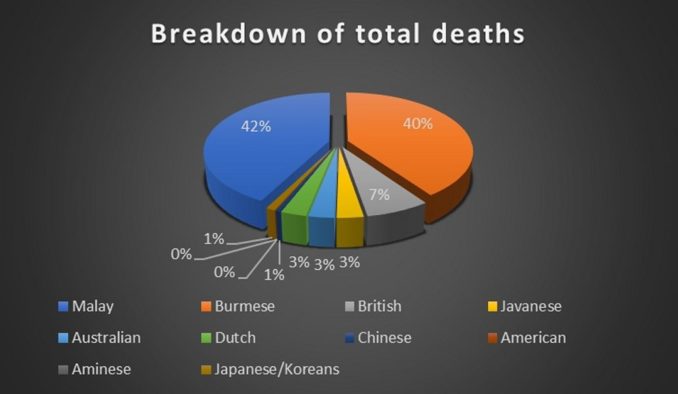

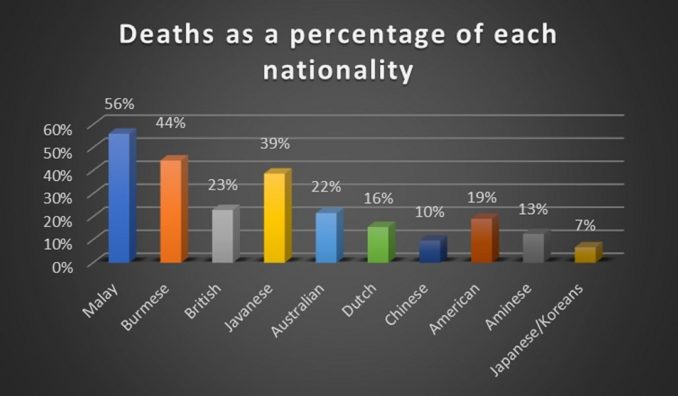

No such conventions existed for the Asian labourers and because many of the records which the Japanese did make concerning the Asians who worked on the railway, were destroyed it is not possible to precisely calculate the numbers who were employed nor their death toll. However, from what records do exist it is possible to compile approximate figures.

War Criminal Trials

After the Japanese surrendered in August 1945, Allied High Command asked the former POWs to report any cases of ill-treatment or brutality by their captors. Identification parades of suspected war criminals were held and those considered to have a case to answer were detained. A total of 120 Japanese and Koreans were subsequently tried for war crimes committed on the railway by the Allied governments of America, Australia, Britain and the Netherlands. Some 111 were convicted of war crimes with 32 receiving death sentences. Those not executed served time in various Allied prisons until they were transferred to Sugamo prison in Japan after the San Francisco Peace Settlement in 1951. All prisoners still incarcerated in 1956 were freed.

© SWMBO & Humbug Slocombe 2024