Following some confusion regarding a caption mentioning both Southsea and Southampton, your humble reviewer of old photographs realised that the 1949 picture in my grandparents’ family album was of a flying boat called Southsea coming in to land at Southampton.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

The flying boat, or seaplane, is a significant and interesting part of British maritime and aviation history, particularly in Southampton. Several firms constructed marine aircraft in the area in the early part of the 20th century with the region also being host to both Navy and Air Force bases on Southampton Water. Civilian flying boat services operated in Southampton from 1919 to 1958, with five different locations used as terminals. During World War II, operations were shifted to Poole and Hamworthy but eventually returned to Southampton.

In 1949 the Southampton Flying Boat Terminal pictured was a significant hub for international seaplane travel and an important transit point for passengers travelling to and from the British Empire. These flying boats, operated by Imperial Airways (later BOAC), were renowned for their luxury and comfort.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

The terminal first came into operation in 1919, on the Royal Pier, providing services to Bournemouth, Portsmouth, and the Isle of Wight. The terminal underwent several relocations over the years, with five different locations used in total. International services began in September 1919 and were run to La Harve by Supermarine. These departed from Woolston on the neighbouring River Itchen.

By 1923, the British Marine Air Navigation Company was operating a service to Cherbourg. In 1924, this company became Imperial Airways, which continued to operate flying boat services until 1929. By 1949 the terminal was located as pictured at Berth 50 between Southampton’s Western and Eastern Docks and, as we shall see, offered destinations much further afield.

Southampton Piers

The Southampton Royal Pier, originally known as Victoria Pier, is a historical landmark with a rich history dating back to the 1830s. The pier was initially designed by Edward L Stephens to provide a docking place for steamers and was inaugurated by Princess Victoria.

Due to damage caused by gribble worms, the pier had to be reconstructed in 1838. In the late 19th century, it was expanded and renovated to function as a pleasure pier. However, during World War I, its tramway services were suspended, and it suffered further damage.

In the 1950s, the pier underwent another transformation to accommodate RoRo ferries. However, in 1979 the pier was closed and has since fallen into a state of disrepair. Despite calls for renovation or reconstruction, no significant progress has been made. Today, the pier’s former gatehouse hosts a restaurant, adding a touch of modernity to the historical site.

After World War Two flying boat passenger services re-started with BOAC flying from Poole but then in April 1948 they relocated to Southampton. Following nationalisation on 1st January 1948 the docks were owned by British Rail with a rail-connected marine air terminal in place. The terminal contained office space, customs and immigration facilities for the bureaucrats as well as a bar and restaurant for the passengers.

Judging from old photos and their captions, passenger trains such as the ‘Ile de France’ boat train, consisting of Pullman coaches, connected with the flying boats.

© Google Maps 2023, Google licence

In the modern day, the old terminal has been partly filled in to become a car park. To the left is a marina and terminal for small passenger ferries. The other side of the marina retains its charm and probably looks as it did in the 1950s.

To the right of the old Berth 50, sits Dry Dock Number Six formerly occupied by the Hardland and Wolf company, better known for their shipyard in Belfast.

A small amount of maritime station rail is still in place next to the stub of what’s left of Dry Dock 6. You can have a look here.

To the right of that is the modern Ocean Cruise Terminal at Dock 46 beyond which is the old Queen Elizabeth II cruise terminal, now used for the import and export of cars. The QEII terminal is still rail-connected are sees ‘cartics’ (articulated car-carrying freight trains) arriving from and departing to the regions.

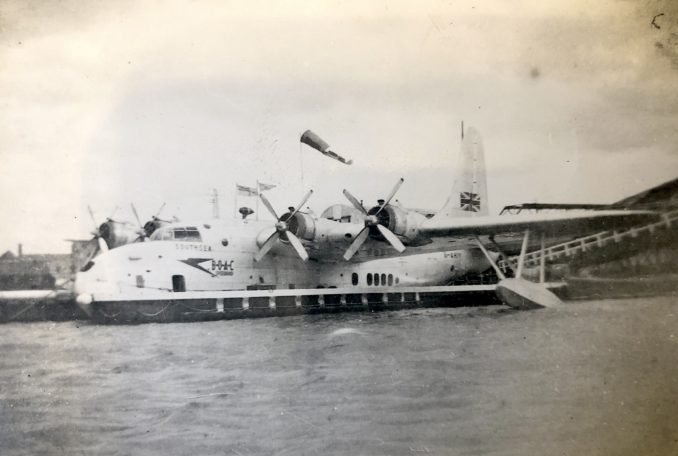

G-AHIY

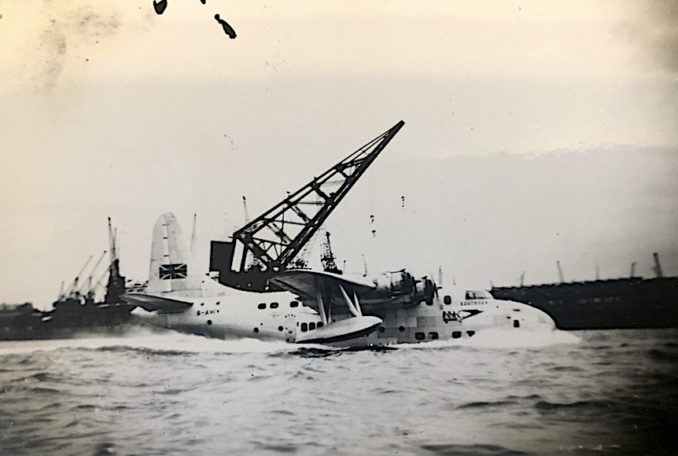

Back at the Southampton Flying Boat Terminal, the registration mark towards the tail of the aircraft is usefully readable. ‘G-AHIY’ tells of a Short S45 Solent Mk 2, the last Mk2 built at Rochester on the Medway in 1948 as manufacturers Short Brothers moved production to their more famous Belfast factory.

The Solent II was introduced by BOAC and could carry 34 passengers and seven crew. It was powered by four Bristol Hercules 637 14-cylinder radial engines, each developing 1,690 hp. Maximum speed was 273mph. A cruise speed of 244 mph gave the Solent II a range of 1,800 miles.

Astonishingly at the time of the photograph, the Solent IIs provided a three-day-a-week service along the Nile to Johannesburg. The journey took four days with no night flying and overnight stopovers in Sicily, Luxor, Kampala and ‘Jungle Junction’ on the Zambesi River near Victoria Falls.

Shortlived, the last BOAC Solent-operated service on the route departed from Berth 50 at Southampton on 10 November 1950, bringing the company’s flying-boat operations to an end. Aquila Airways took up the mantle and continued to fly the aircraft until 1958 when the company gave in to the inevitable with the jetplane doing to flying boats what the gribble worm does to old wooden piers. Simultaneously, the last trains ran from the maritime station.

Further afield, the Solents fared a little better. The gloriously named Tasman Empire Airways Limited (TEAL) operated four Solent IVs and one Solent II between 1949 and 1960 on their scheduled routes between Sydney, Fiji, Auckland and Wellington. The last TEAL Solent service was flown between Fiji and Tahiti on 14 September 1960 by ZK-AMO, RMA Aranui, which is now preserved.

About THAT crane

As for the crane in the background, this is another notable piece of engineering; the Southampton Southern Railway Floating Crane No.1. which worked in the docks for over sixty years.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

Its pontoon was built by the Furness shipyard, Stockton, and launched in August 1923. The crane itself was built and added to the pontoon in 1924 by Cowans Sheldon of Carlisle, my grandparents’ home town. Upon completion, it was towed to Southampton and commissioned into use on November 11th 1924. Number One was used to move large parts of ships under repair while alongside Southampton’s floating dock.

During the Second World War, the crane was transferred to the Clyde for ‘Special Duties’, returning to Southampton in 1946. The crane had three separate hoisting gears, the main one having a capacity of 150 tons, on two hooks, at a maximum radius of 106 feet. The crane was not self-propelling but had capstans on the pontoon for hauling itself into position.

In 1962, the steam-driven machinery was replaced by diesel-operated equipment. In 1985 the crane was dismantled and replaced by the 200-ton crane ‘Canute’.

A subsequent Cowans Sheldon order saw a similar crane built for the Port of London. No strangers to big crances, as early as 1908 another 150-ton capacity floating crane had been dispatched from Carlisle to the Kawasaki Dockyard in Japan.

In the modern day

Harland and Wolf and Short Brothers (now part of Kanas-based Spirit AeroSytems) continue in Belfast, although diminished compared to the 1950s.

Southampton Docks thrive. According to the blurb, the port has various berths with different depths and berthing distances, suitable for diverse maritime operations. In 2005, the port handled 38.8 million tons of cargo, but the plan was to handle almost 52 million tons of cargo per year in the 2020s and over 62 million tons by the 2030s. The port also has a reserve of 324 hectares for future expansion.

Elsewhere, Cowans Sheldon of Carlisle is a retail park with a big (Indian-owned) B&M Store on it. Oh well.

Acknowledgements and further reading

Disused Stations, Southampton Flying Boat Terminal

To The Victoria Falls, Flying Boats

© Always Worth Saying 2023