In the 1980s Ali Porteous and Tim Cooper were filmmakers taking extraordinary risks. Having filmed the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka, they heard about a suspected genocide in Central Uganda and hooked up with an NRA liaison cell in London. They reached Uganda and crossed governmental lines in early 1985. They spent six weeks in Luwero, constantly moving. Getting images out to the world became a bigger challenge. They entrusted footage to NRA, and crossed back into government territory disguised as missionaries.

They were editing footage at Channel 4’s HQ when a Ugandan minister unexpectedly arrived, bearing a suitcase full of cash and a simple request: “Don’t show the film.”

The bribe declined, but the official’s instincts were sound. Coming on top of Pike’s account in The Observer, their coverage provided Western governments with their first sustained glimpse of the “Marxist bandit” M7 and his movement. M7 came across well, serious, articulate. It was enough to convince many Western policymakers a transfer of allegiance might be in order.

On the cusp of major deployment, NRA still needed more weapons. Before travelling abroad to muster diplomatic support, M7 divided his forces into two. Taking with him a contingent of sick and elderly civilian stragglers, Fred Rwigyema trekked west toward the Ruwenzori mountains, the NRA rump remained in Luwero.

Obote’s army interpreted this, the NRA was about to collapse. What followed instead was a two-pronged assault by both NRA forces, operating 250 miles apart, stretched government forces to its limits.

The mood in the UPC coalition and its military ranks was becoming mutinous, as the campaign turned against them. Acholi soldiers had become convinced they were taking all the casualties while their Langi colleagues remained non-combatant.

Yet Another Military Coup

Tito Okello,

Unknown photographer – Fair use: Provides identification, no alternative, low resolution

In July 1985, three days after Fort Portal had fallen to Rwigyema’s NRA forces, Uganda woke to another military coup, this one staged by Tito Okello and Bazilio Olara-Okello, two Acholi generals. Obote 2 was over, having fled first to Kenya then to Zambia. New President Tito Okello made the customary gesture releasing political prisoners his predecessor had jailed with truckloads of inmates driven to Kampala City Suare and dumped.

In the coup’s wake Okello, who’d formed a marriage of convenience with the Democratic Party, set up a military council and offered M7 a seat at the table if the NRA suspended its campaign.

Kenya President Moi offered to host peace talks in Nairobi. Sensing overall victory was close, M7 was in no hurry to negotiate, making more diplomatic demands ahead of any peace talks, while at the same time, conquering more territory in Western and Central Uganda. By August 1985, Kampala was a divided city, with five separate militias making up a UNLA fractious junta controlling five different hills.

After the surrender of famished UNLA troops in barracks at Masaka and Mbarara, all that remained was a multipronged assault on Kampala, leaving roads east and north open towards Kenya and Sudan. The Okellos boarding helicopters and flying to Gulu signalled the end.

More change At the Top

27th January 1986, the NRA leadership met in the Kabaka’s former palace in Lubiri to discuss and agree the way ahead. Agreeing to a National Resistance Council (NRC) in the absence of an elected parliament, they appointed M7 president. With previous politicians failing to control the military, the new government sought to put the military, if not in control of politicians, then at least in a central role. 40% of the NRC seats would go to the NRA fighters in almost every department; defence, police, civil service, foreign service. A ragged victory parade drove through the centre of Kampala with M7 accompanied in the lead jeep by Fred Rwigyema – the first to be presented during the subsequent medal ceremony.

At the fall of Kampala, NRA was 16,000 in strength, of which roughly 4,000 being Banyarwanda, many appointed to senior key positions in the majority of ministries. With hindsight, perhaps the Bush War was too successful for the good of modern Uganda or the Great Lakes region. For M7 and his cadres emerged convinced they could both wage, and win, a virtuous war. The impact victory had on M7’s young Banyarwanda acolytes, was more profound. They emerged believing they could achieve the near-impossible, convinced they were immune to the limitations that overwhelmed lesser mortals.

The problem with history is not that people fail to learn its lessons, but they learn the wrong ones. There were glaring differences between Luwero and northern Rwanda that meant policies that worked in the former in the 1980s would fail in the latter in the 1990s. But, flush with confidence, only some of M7’s “boys” were disposed to notice.

Fred, now a Maj Gen, had been named deputy commander in chief of the armed forces, second only to M7 when it came to military decision-making. Kagame, appointed major, was Dir. of Fin. and Admin. in the new Mil. Int. Department set up by Gen Mugisha Muntu.

Kagame’s true character started to rise to the surface. He would order the arrest of Ugandan businessmen simply because they had made money, honestly and legally.

Dr Peter Bayingana, who’d abandoned a medical practice in Nairobi to join NRA, was appointed Dir of Uganda’s Army Medical Services. Major Chris Bunyenyezi, Cdr of 306th Bde, became head of NRA’s training service. Frank Rugasara was in charge of the MoD budget. Patrick Karegeya was appointed Asst. Dir. at Mil. Int. focusing on counterintelligence.

Uganda’s entire administrative system was being restructured and overhauled, using resistance councils as building blocks. Uganda’s war-shattered economy needed a massive electro-shock, and M7 turned for help to the IMF and the Paris Club of donors, while also urging Asians to return and claim their weed-infested plantations and businesses. The Bush War over, but fighting was not, it hadn’t died away. NRA’s enemies had fled back north to tribal lands as well as Sudan and Zaire.

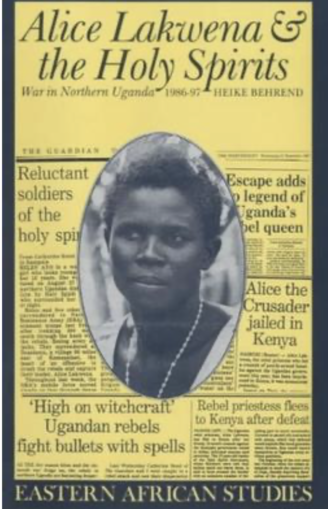

Alice Lakwena and the Holy Spirit Movement

Alice Auma Lakwena,

Unknown photographer – Fair use: Provides identification, no alternative, low resolution

Among many fractured groups, who’d supported Amin (FUNA – Former Ugandan National Army), Obote (West Nile Bank Front), Okello et al (Uganda National Rescue Front), one proved formidable. The Holy Spirit Movement led by Alice Lakwena (a spirit medium from Gulu) who’d heard voices telling her to liberate Uganda. A “Ugandan Joan of Arc”, she led her forces into battle carrying a lamb, with her troops told if they smeared themselves with shea butter, they would become bulletproof.

In charge of the campaign, Fred Rwigyema waited for the Holy Spirit Movement to get as far as Magamaga, a barracks East of Kampala, then the NRA troops simply mowed down the whole force. Her forces crushed, Alice fled to Lokichoggio refugee camp in northern Kenya (established originally to deal with refugees from Sudan/South Sudan). Here, she briefly “barked at the Moon again” insisting with two guns she could capture Uganda in three days.

She is now living in Kangemi, a satellite town just north of Nairobi, having been given a free plot of land and a house by the then MP Fred Gumo. She’s still alive (and the author last saw her eight days ago in Kangemi market). Her cousin and former choirboy Joseph Kony rebadged the Holy Spirit Movement into the Lords Resistance Army (LRA) and is currently in hiding in Kafia Mingi, a small settlement ENE of Wau in South Sudan.

However, the Banyarwanda “boys’” commitment to Uganda was not as it had been. Rolling small military campaigns began to feel like “someone else’s fight”. What had been left unsaid among them during the bush years, now needed to be explored and they began meeting after work, in secret. Ideas would only take concrete form if someone took the lead, provided the community with a focus, voice, end destination. It wasn’t Kagame.

© AW Kamau 2023