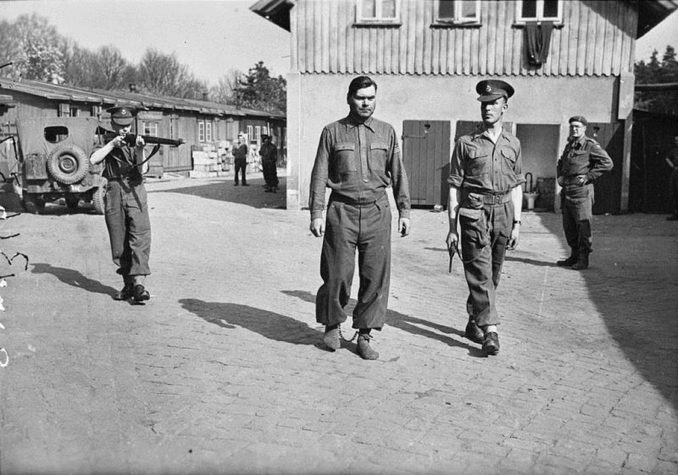

Malindine E G (Capt) No 5 Army Film and Photographic Unit, British Army, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A fellow poster suggested that I should write a piece about the art of…er…writing since it has become, rather later in life than I would have liked, my profession. Flattering as this suggestion is – and there is nothing a writer likes than to be able to waffle on endlessly about themselves – I really wanted to link it to something a bit more pertinent to the GP ethos and which everyone may, hopefully find interesting and thought-provoking.

Let’s take a good look at the photo at the top of this piece. Many of you will probably be familiar with the image as it is one that has been reproduced many times in histories and documentaries of the Second World War. It shows Josef Kramer, the erstwhile Kommandant of Belsen-Bergen concentration camp shortly after its liberation by the British army in April 1945. Putting aside, for the moment, that this is probably one of a number of staged propaganda pictures my eye was immediately drawn not to Kramer but to the figure on the left of the picture – the soldier holding up his rifle as if he was about to fire. My imagination immediately whirred into action. Who was this? Why has he got his rifle at the shoulder when the officer is suitably armed and Kramer is in leg irons? It is a simple, impenetrable, question which only served to prick the curiosity of this writer even further. Thus began the weeks of research and development of a vital part of the story which would lead to turning the novel on its head, moving motives from one leading character to another and providing a convincing psychological background to the events that would engulf and destroy both the guilty and innocent in the years post 1945.

The British army entered Belsen-Bergen in April 1945 and I had two of my main characters be part of that first contingent and experience what has been documented as one of the most grisly scenes of the war. Bearing in mind that some of these soldiers would already have experienced the D-Day landings and skirmishes with the Germans in the previous nine months they would already be suffering from fatigue and what is now termed PTSD. Indeed, I had one of the characters witness the cold-blooded murder of a female collaborator by her estranged Maquis husband.

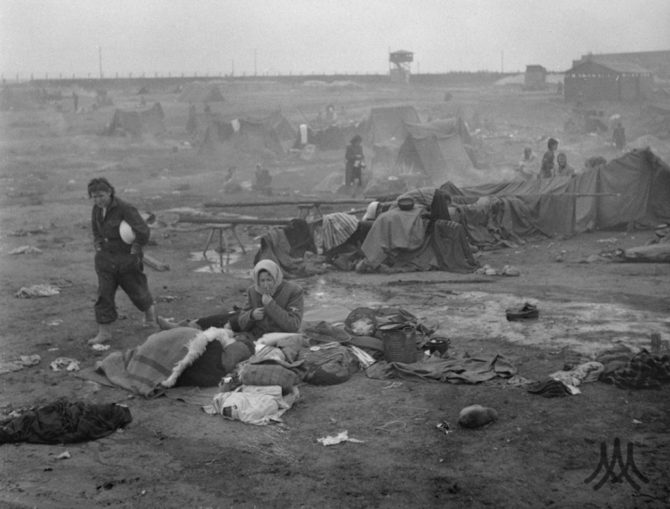

Public Domain

Such events tend to get lost in the wide-ranging overview of global events but as a writer I am more interested in the particular, that single incident which can enlighten us as to the real, filthy, distortion of humanity in extremis.

Looking at the picture at the top of this piece and the one immediately above I fashioned a story about that single moment. The unknown soldier with the rifle I now named the fictional Reg Manley and he had already experienced the horrors of the camp. Here’s the section from the novel that covers this scene:

And the stink rolled out from the huts as dense as a suffocating London smog, hanging thick and liquid as if trying to smother the onset of the German spring. A continuous cloud of dust swirled backwards and forwards wreathing the creatures in a ghostly aura as they wandered aimlessly between the huts. Beyond the wire, the season was beginning to flower with fresh yellowed gorse and greening trees that surrounded the camp but in these barbed enclosures everything was dead and dying, the flattened remains of grass, the churned mud, the sticks of humans.

Reg stopped at one woman who sat on her haunches. She had a full head of hair so he suspected she couldn’t have been here that long.

She reached out with her hand: “Wohin ist er gegangen, mein geliebter Sohn?”

Reg bent over her. “What, love?” He looked into her face and saw a dark despair reflected in her eyes.

“Warum habt ihr getötet meinen Sohn?” Her voice trailed off in a wail, her head slumping into the rags around her chest.

He turned to Daffin. “How’s your German? What’s she saying?”

“She’s asking you why you killed her son. I think she believes you’re a German soldier, sarge.” Daffin looked at Reg who had taken a step back.

“Bloody hell! Put her straight Daphne. I don’t want anyone to think I’m a fucking kraut.”

Daffin spoke to the woman, placing his hand on her shoulder.

She looked up and peered at the soldiers around her, a look of understanding finally coming to her face. She took hold of Daffin’s hand, gracefully lifting it from her shoulder and kissed it, holding it lovingly against her cheek, rocking back and forth on her haunches. Reg knelt beside her and took up her other hand, holding the delicately framed fingers carefully, frightened that they might break. She moved her face from hand to hand, alternatively kissing his and then Daffin’s. Reg could see her tears roll over the back of his hand and at that moment something broke inside of him. The touch of a woman had always eased his heart and even here, perhaps especially here, amongst all this death and decay, he felt utterly overwhelmed.

A stir of feet behind him made Reg look around. The colonel, pistol out and pushing and shoving the camp commandant whose ankles were now shackled with a chain, was shouting at the prisoner: “You fucking bastard! What is this? What is all this? What have you been doing here, you bastard scum?”

Reg watched as the commandant shuffled by. Just ahead he could see a photographer ready to take a picture and everything just blew over him; the French woman shot by her husband, the endless killing, the rotting cloud of humanity in this hell, those tears still wet on the back of his hand. He raised his rifle to his shoulder, eased the spring and pulled up a bullet into the breech. It was all so quick that Daffin fully expected his sergeant was going to shoot the camp commandant there and then. Reg simultaneously heard the click of the camera and the colonel barking at him:

“Stand back that man!”

The procession had stopped and Reg sensed everyone was looking at him, everyone except the prisoner who stood stock still, facing away.

“Lower that rifle, sergeant! That’s an order.” The colonel still pointed the pistol at the shackled man. “We’ll deal with this bastard in due course. For the moment I need him to tell me what’s been going on here.”

And Reg heard George say; “It’s OK, Reg. Leave it eh?” A hand on his shaking arm, firmly pressing down. “Let’s see what we can do for these poor devils. Perhaps we can save one or two.”

Later Reg was to say that if he had already seen inside the barn before that moment he wouldn’t have hesitated to pull the trigger. George said he would have given Reg a medal if he had.

[Daffin, one of the soldiers in this piece is nicknamed “Daphne”, primarily because he is university educated and becomes the butt of a number of jokes – which he takes in good part].

It is difficult for those of who have never served in the armed forces to begin to imagine the stress that those who defended these shores in the First and Second World War and those who continue to serve Her Majesty in countries far removed from our comparatively peaceful isle. The case of Marine A, refused bail just before Christmas, is, I would argue, both a failure of imagination on the part of the judiciary and a serious weakness of an Establishment that is deeply immured in political correctness. That it sees fit to serve the enemy by prosecuting its own and allows money-grubbing outfits such as Public Interest Lawyers and Leigh Day to suck at the public teat in order to prosecute soldiers who may well have experienced what my fictional characters did is a scandal that should have been cleared out from the legal Augean stables years ago.

To those both serving within the armed forces of this country today or who are now retired, I dedicate this piece.

Thank you.

Roger’s book:

© Roger Ackroyd 2022 (republished from 2017)