Introduction

From January 1943, with the commencement of American daylight bombing of German targets complementing the existing night time raids by the British Air Force, Luftwaffe superiority in the skies over Germany and its occupied territories was being challenged by the Allies. Although it should have been obvious at the time that Germany could not hope to win the war, desperate new solutions were sought in the form of ‘revenge weapons’ and while some, such as the V1 and V2 rockets and the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter were technically very advanced, many other promising projects were destined never to be fully developed due to shortages of materials, skilled manpower and above all, time.

During his time at Fieseler, Erich Bachem had considered the possibility of a vertical take off jet-powered interceptor and this, known as the Fieseler Fi-166 I, was basically a twin Jumo 004 jet-engined aircraft attached to a V2 type rocket then being developed at Peenemünde by Werner von Braun and his team. After launch the rocket would separate from the aircraft and parachute to the ground to be re-used while the fighter would continue to its target, engage the enemy bombers and land back at its home airfield. This proposal was however deemed by the German air ministry to be impractical. Undeterred, Bachem then produced an alternative design for a large, two-seat interceptor with its own rocket motor, the Fieseler Fi-166 II, that did away with the need for an external A5 rocket booster but this too was rejected on grounds of impracticality.

What was needed was a cheap interceptor aircraft that could be built from readily available materials by semi-skilled and unskilled workers in small, poorly equipped workshops.

The Bachem BP-20/ Ba-349 ‘Natter’

Bachem had seen for himself formations of American bombers heading at 23-25,000 ft altitude to attack German industrial centres and had realised that the best way to counteract this threat would be to use heavily armed, rocket powered, vertical take off interceptors that could climb to attack them in the space of one to two minutes from launch. Bachem discussed his ideas with Luftwaffe ace Adolf Galland who promised to raise them with the Armaments Minister but despite this his requests for funding were again refused.

Bachem’s amended proposal was that his interceptor would be launched by ground staff and guided close to and above the attacking bombers by autopilot. When in position, the pilot would take control, select a target, jettison the plexiglass nose cone and aim and launch a salvo of unguided air-to-air rockets. In the case of the Föhn rockets a single hit would be sure to down a bomber. After making the attack the pilot would then dive to around 10,000 feet when he would deploy a braking parachute that would automatically eject him from the cockpit and while he descended by personal parachute, the rear part of the aircraft would also parachute down so that it and the precious rocket motor could be re-used. The cockpit and nose cone would simply fall away and be sacrificed. This proposal had the advantage of doing away with the need to make a gliding descent which, as had been seen with the Me-163, left the aircraft very vulnerable to allied fighter attack.

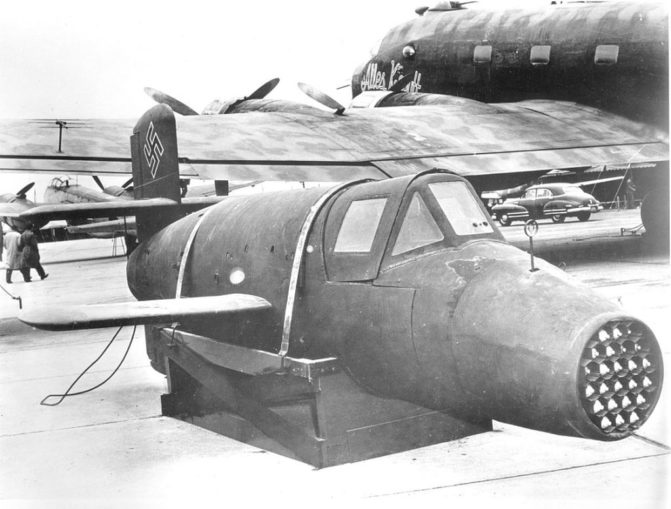

Armaments considered for the interceptor included a photo-electric cell initiated Borsig SG 119 49 barrel mortar; 33 R4M 50mm rockets; 24 Henschel Föhn 73mm rockets and two 30mm MK108 cannon with 30 rounds per gun.

Undaunted by the rejection, Bachem requested a personal audience with Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS who, interested in the proposal, offered to site a concentration camp near Bachem Werke to ensure a constant supply of labour. This idea horrified Bachem who also refused to countenance the idea of producing an aircraft with a concrete nose designed to ram a bomber in a suicide attack. Pilot safety was one of Bachem’s priorities. He argued that he needed some skilled and semi-skilled labour to build the wooden aircraft and Himmler agreed to mobilise disabled skilled men to achieve this. The project was to be controlled by SS Obergruppenführer Hans Kammler who was also in charge of the V2 rocket development programme.

The project now known as the Ba-349 was given the name of ‘Natter’ (Adder) by its designer and was initiated in August 1944. Wind tunnel tests of scale models were carried out in September 1944 that showed the aircraft to be stable at speeds of up to Mach 1.0. The construction was very simple and here Bachem drew upon his experience of designing lightweight, high-performance gliders. The fuselage was a glued and nailed wooden monocoque covered in a plywood skin. The wings had no control surfaces, these being incorporated into the cruciform tail. The pilot was protected by armoured bulkheads and a bulletproof windscreen.

The first prototype Nattern were towed to 18,000 feet by a Heinkel 111 and released for glide testing which confirmed the aircraft’s excellent handling at speeds from 125 to 425 mph.

Launch and flight testing

As the proposed power plant, the Walter HWK 109-509A2 was not available, the HWK 109-509A1 as used in the Messerschmitt Me-163 had to be used and this at 3,500 lb thrust at maximum power was insufficient on its own. To overcome this, four Schmidding SG34 solid fuel boosters each producing 1,100 lbs of thrust would be fired at launch and jettisoned by means of explosive bolts when exhausted after a 10 second burn.

The Natter was to be launched vertically from a 66 ft tall metal launcher, three rails on which engaged with the tips of each wing and the ventral tail fin. At launch, the pilot would play no active part and would simply be a passenger until the aircraft reached it operational altitude in the vicinity of the enemy bombers in around 60 seconds from launch at which point he would take the controls, make his attack and escape.

The first successful unmanned launch from the experimental tower took place on 22 December 1944 using only the solid fuel boosters. In February 1945, the first Walter rocket motor was delivered and on 25 February with a dummy pilot in the cockpit, the Natter made a perfect take off under a combined total thrust of 6,500 lb. The aircraft separation also worked perfectly with the dummy pilot and the rear portion of the fuselage with its valuable motor both descending as planned by parachute. Unfortunately, residual rocket fuel comprising T-Stoff (hydrogen peroxide and water) and C-Stoff (Hydrazine hydrate and Methyl alcohol) a highly volatile mix that was known to dissolve human flesh on contact, ignited on landing and the fuselage and motor were destroyed.

Manned test flight

From January 1944, Bachem had been under increasing pressure to undertake a manned flight but he was reluctant to risk a pilot without further unmanned testing and development. Despite Bachem’s reservations and due no doubt to intense pressure from the SS, Lothar Sieber, an idealistic and daring 22 year old test pilot, climbed into Natter M23 on 1 March 1945 for the first ever manned vertical take off in a rocket-powered aircraft.

At Sieber’s insistence, the Natter’s automatic guidance was switched off and Bachem briefed him to execute a half roll should the Natter veer off course. All went well at first and the Natter launched without problem before being seen to half roll with the cockpit canopy inexplicably coming off shortly after the booster rockets separated and the aircraft disappeared into the clouds. At that point the rocket was still firing but a few moments later, the Natter reappeared diving vertically out of the clouds before hitting the ground seven kilometres from the launch site in a violent explosion that caused a five metre deep crater. Eyewitnesses fully expected to see Sieber descending from the clouds by parachute but unfortunately he had not been able to eject from the Natter and he died inside its cockpit.

The post-crash investigation

At the crash site very little of either the Natter or the pilot remained. According to Bachem,

“We found the machine completely destroyed. The pilot had made no attempt to escape. Of our comrade we found only the left hand with a piece of forearm and a left leg that was ripped off below the knee.”

A small piece of Sieber’s skull was later found in the crater.

The recovered cockpit canopy latch was found to be damaged suggesting that it had either not been correctly fastened prior to the launch or had been released by the pilot in an attempt to escape. It is possible that Sieber’s left arm and leg had been partially outside the cockpit at the time of the impact. Another theory was that the canopy fastening had failed causing the pilot’s head to be snapped back against the upper bulkhead breaking his neck and killing him instantly.

It wasn’t until a more forensic excavation of the crash site was carried out in 1998-99 that researchers discovered the remains of an SG 34 rocket booster that clearly had not separated during the Natter’s launch. This would have affected the aircraft’s stability in flight and also prevented the release of the braking parachute which was stored under a hatch covered by that particular booster.

It is most likely that during the short flight Lothar Sieber had become disorientated in the poor visibility and had pulled back on the controls while flying inverted. It is ironic that the Siemens gyroscopic control system that had been proven to be reliable and effective would probably have saved Sieber’s life had it not been de-activated at his request. This confirmed Bachem’s view that all Natter operational launches should be fully automated.

The cockpit canopy latch was redesigned and the pilot’s headrest was incorporated into the cockpit bulkhead rather than, as previously had been the case, being part of the canopy. A locking device was added to the controls to be released by the pilot when the aircraft reached its operational altitude prior to the attack run.

Natter production

According to Bachem, 38 Nattern were produced prior to the end of the war but of the 200 ordered by the SS (150) and the Luftwaffe (50), none was delivered. 14 Ba-349s were finished or almost finished by April 1945 including three that were launched from experimental wooden pole field launchers; six were burned as the Allies advanced; four were captured by the Americans in Austria and one was captured by the Red Army.

Operation Krokus launch sites

Three Natter launch pads designed to take the wooden launch poles and constructed in Hasenholz wood near the Stuttgart-Munich Autobahn were rediscovered in 1999. Comprising a circular concrete base with a square hole at its centre for the wooden pole, these launch sites can still be seen.

Eight pilots who had volunteered to fly the Natter operationally were in training at Bachem-Werke from January 1945, the intention being to launch an attack on enemy bombers on Hitler’s birthday 20 April although at that time the launch sites were not ready. The US 10th Armoured Division arrived in the region that same day heading straight for Hasenholz causing the Natter team to destroy their aircraft and withdraw to Waldsee.

The Natter today

Only one genuine Natter currently exists in an unrestored condition at the Smithsonian Institution’s Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Suitland, Maryland. Other examples are either completely modern reproductions or composites of new and original components.

It is of course sad that such a young and brave pilot should have to die so horribly in the service of his country but had that first manned flight gone to plan, the Natter might well have been rushed into operational use with potentially lethal implications for many Allied bomber crews. In 2016 a German black and white film ‘Das Problem des Schnellstfluges’ was released that recreated the events of 01 March 1945 as seen through the eyes of a 10 year old eyewitness.

After the War

In 1947/48 Erich Bachem left Germany via Denmark and Sweden to settle in Argentina where he set up a factory making guitars with interchangeable bottoms. It has been suggested that his emigration might have been due to fear of being taken to the USA to join Werner von Braun and his team as part of Operation Overcast. In 1952 Bachem returned to Germany to become technical director of his father-in-law’s factory designing mining equipment and long-distance diesel locomotives.

It was during this period in 1957 that Erich Bachem turned his mind to another completely different project that has had a significant impact on my life albeit 50 years after his death and that’s the topic that we will explore in Part 3.

Postscript:

Since writing Part 1 of this series featuring the Fieseler Storch, I have watched a YouTube documentary by Mark Felton entitled ‘Last Flight from Berlin 1945: The Reitsch/vonGreim Escape’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iIpdoM5_i_A in which he states that according to Reitsch herself, she did not pilot a Storch out of Berlin but, having turned down the offer of seats on a Junkers Ju 52 transport aircraft so that injured personnel might be evacuated, she and von Greim were flown out in an Arado Ar 96 trainer with a Luftwaffe sergeant at the controls.

© Tom Pudding 2022