Previously, my colleague Fred Brownbill wrote of US Navy SEAL Marine Commander Brian Bourgeois, commanding officer of SEAL Team 8, who was killed in the first week of December 2021 while fast-roping from a helicopter during a training exercise at Norfolk, Virginia.

A friend of Mr Brownbill who served under Marine Commander Bourgeois paid the following tribute,

“He was a hell of a good guy. He was one of my LTs in Iraq. No job too hard, he exemplified “Message to Garcia.” It was a privilege to have known and worked with him. He represented the best of all uniformed service members and was highly regarded as one of our best SEALs.”

After expressing our condolences to the commander’s wife and five children and nodding in respectful agreement towards Mr Brownbill’s fitting tribute, we might ask what was that message about?

In 1899, Elbert Hubbard wrote the essay Message to Garcia as a worthy tale of derring-do executed with the individual initiative and meticulous attention to detail required to deliver battle orders to an ally of the Americans, General Calixto García.

As the events described took place during the Spanish-American war in mountainous inland Cuba, it is perhaps difficult for an audience this side of the Atlantic to grasp. Is there a story closer to home that might provide the same inspiration?

No doubt there will be many. May I humbly present that of Lieutenant David James, MBE, DSC, RNVR?

***

David Pelham James was born on Christmas Day 1919. An old Etonian and the son of RAF pioneer Sir Archibald William Henry James MC, he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve at the outbreak of World War II having left Oxford’s Balliol College during his second year in order to enlist.

Royal Navy monitor HMS Marshal Ney underway during trials,

Royal Navy official photographer – Public domain

By June 1940, he was a midshipman on HMS Drake. The end of the following year found him on motor gunboat duty, being the second in command of MGB No.63. On the 28th February 1943, during an operation in the low country literals that saw him earn a DSC, he was sunk on MGB 79. Rescued by a German trawler, the survivors were taken ashore to the Hook of Holland, made prisoners of war and sent to the Marlag prisoner of war camp in northern Germany.

Liberated naval and merchant seaman POWs at Marlag,

Gordon (Sgt), No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit – Public domain

Marlag is an abbreviation of marinelarger, meaning naval camp, this one being at Westertimke, on a branch line halfway between Bremen and Hamburg. During the war other notable inmates were to include, Captain Micky Burn of No. 2 Commando captured during the St Nazaire raid, Lieutenants Donald Cameron RNR and Godfrey Place RN taken prisoner during the X-craft attack on the Tirpitz and official war artist Lieutenant John Worsley RN.

In the camp, James converted to Catholicism and planned his escape. With the wash block being helpfully outside the perimeter and the guards being lax, it was possible for members of the bath party to escape out of a shower room window which James did on December 8th 1943.

Disguised and with accompanying forged documents, his rouse was as a shell shocked Danish electrician making his way to Bremen for a medical appointment. This disguise served him well, arriving in the city by local train where, in the crush at the toilets, he abandoned that disguise and adopted a second one hidden beneath his Danish electrician’s greatcoat.

Wary that POWs and their guards often travelled on the branch line to Bremen (meaning his disguise proper might be recognised), he took the precaution of waiting until a change of trains before assuming his preferred alter ego.

As the toilet cubicle door opened, James emerged in his own Royal Navy uniform, customised with a single flash to appear to be a Bulgarian naval attache. Accompanying forged documents ordered German forces to offer him every co-operation as he travelled the Reich inspecting ports for ‘technical reasons’, all signed off by an invented official at the German Foreign Office.

The attache’s name? Bagerov, pronounced an easy to remember ‘bugger off’.

The documents had been forged in the camp, the uniform altered by a civvy street master tailor called John Wells. The Bulgarian Navy had been chosen as they only had three ships and no one from the Wehrmacht was likely to have seen their officers.

Németország, Hamburg, főpályaudvar, vonatok,

Lőrincze Judit – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

From Bremen, this time on the mainline, he travelled back on himself continuing all the way to Hamburg and from there to Stettin but struggled to find the port area let alone any neutral shipping capable and willing to take him across the Baltic to neutral Sweden.

Moving on to Lübeck, his fortune improved – briefly. Timing an uninterrupted stride to coincide with the turned back of a dock sentry’s predictable beat, he was able to climb the gangplank of a Swedish coaster. Refused passage as the vessel would be coaling the next day and crawling with German stevedores, and missing a departing adjacent vessel by seconds, James was forced to leave the dock area but in doing so was stopped by the sentry. Lacking a specific pass for that port, he was taken to the River Police building (der Wasser-Schutz Polizei). There, as proof you should never underestimate your enemy, a ruddy-faced overweight bureaucrat spotted a mistake on the would-be Bulgarian attache’s fake documents.

The Chief of Police for Cologne (whose name the POWs had spotted in a German newspaper) and whose forged hand had added ‘Identity checked by telephone from Berlin’ to Bagerov’s papers, should have signed himself ‘Polizei Prasident’ not ‘Poluzei Kommissaf’.

During the previous few day’s wheeze, German officials bought James’ rail tickets, hung his RN cap on waiting room hat stands next to Nazi headgear and brought him beer. He ate for free in German worker’s canteens, chatted to home on leave officers from the Akrika Korps and shared a compartment with the Hitler Youth – all in his Royal Navy uniform. While wandering Stettin, a German civilian stopped him, told him he wasn’t safe because of the air raids and paid for his ticket to Lübeck.

Sent back to Marlag and following his punishment, James re-doubled the effort to escape. In between times, the rouse of nipping out of the shower window and not being reported missing for a whole week until the next roll-call had been kiboshed by Jerry who began counting them all in and counting them all out on every wash trip.

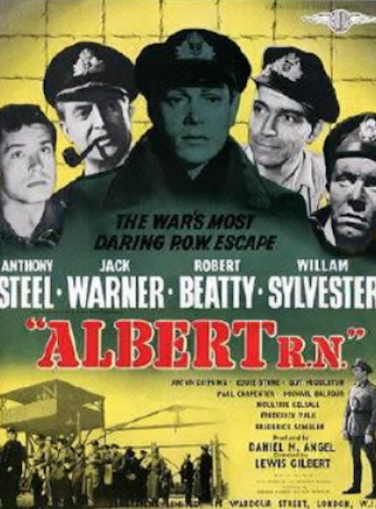

A cunning plan was hatched, one that was immortalised in a 1953 film Albert R.N. starring Jack Hawkins.

Albert R.N.

Fair use via Wiki Commons

Albert was a disassemblable colleague, crafted with the help of war artist Worsley, that could be smuggled into the showers in bits, assembled and, from an obergruppen tallyman’s distance, appear to make up the numbers in a headcount. In late 1944, James escaped again, this time disguised as a Swedish merchant seaman.

The plan went well until, while sticking to his cover in a bar, a German addressed him in Swedish explaining he’d lived in Sweden for many years before the war. Fortunately, James could speak the language fluently. Aged 17, he’d sailed around the world on a 4-masted Eriksson windjammer called the Viking.

Following a successful escape, James presented himself to a British Military attache in Stockholm. A communication dated 8th March 1944 from our Embassy to the Admiralty, summarised his escapade and concluded,

“He is a resourceful young man, however, and well worth the £200 he looks like costing us for his passage.”

Back in England and with the war still raging, given James’ experience and knowledge of escape, forgery, disguise, the ports of the Baltic and his fluency in German and Swedish, the Senior Service sent him to …. Antarctica.

As part of Operation Tabarin, meant to shore up Britain’s claim to the Falkland Islands and parts of the Antarctic continent, he wintered in Graham Land and proceeded to Hope Bay at 63o 23′ South, working as a surveyor. A 1,390ft conical mountain called James Nunatak is named after him. A nunaket being an outcrop of rock from an ice field or glacier.

Stone hut of the swedish Antarctic Expedition at Hope Bay,

Samuel August Duse – Public domain

At the end of the war, his adventure continued as he became an advisor to the 1948 film Scott of the Antarctic and starred as a body double in some long-distance shots. He wrote a book about the experience entitled Scott of the Antarctic: The Film and Its Production. The following year he published That Frozen Land: The Story of a Year in the Antarctic.

***

Having had a good war, he returned to England and began a life more ordinary. Marrying in May 1950, his bride was Jaquetta Mary Theresa Digby, 9 years his junior and daughter of Edward Kenelm Digby, 11th Baron Digby. Simultaneously he became one of the Churchills, his wife’s sister being Pamela Churchill Harriman, first wife of Randolph Churchill, a subsequent spouse of W. Averell Harriman and eventually Bill Clinton’s US Ambassador to France.

During the following eight and a half years of their marriage, Jaquetta presented the now author and publishing executive with six children – four boys, two girls.

His written works also included Wavy Navy, Some Who Served, co-authored with James Lennox Kerr, a fellow naval reservist mentioned in despatches at Omaha beach. ‘Wavy’ references the wavy gold braid on naval reservists cuffs which distinguishes them from regular Royal Navy officers and no doubt helps to baffle the likes of the Afrika Korps and Hitler Youth.

Outward Bound opened with a foreword by the Duke of Edinburgh. In Praise of Fox Hunting was a series for The Field. Added to these was his own wartime biography entitled Prisoner’s Progress.

James was the official biographer of Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, VC, KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCIE, VD, PC, FRSGS (known as Roberts of Kandahar) whose life, never mind yours and mine, made Leuitenant James’ seem rather dull. Born in Cawnpore, India, the Field Marshall died touring trenches during the First World War – aged 82.

In 1959, James became Conservative Member of Parliament for Brighton Kempton.

Partway through his Parliamentary term, he was stalked and ambushed on a February morning at Victoria Station’s ticket barrier after arriving in town on the 08:54 from Haywards Heath. The assailant? TV presenter Eamonn Andrews armed with the big red This is Your Life book.

During the programme, James was re-acquainted with Captain Uno Morn of the Viking, Able Seaman John Baker of stricken MGB 79, Paul Shadrich the Lübeck policeman who recaptured him and tailor John Wells who, in the interim, had become Lord Mayor of Westminster.

Also in that series of This is Your Life; Max Bygraves (fitter in the RAF), Charlie Drake (RAF), Cocco the Clown (conscripted to both the Red and White armies during the Russian Revolution), Dora Bryan (ENSA) and Acker Bilk (National Serviceman, Suez Canal Zone). Different times.

Interested in the existence of the Loch Ness Monster, in 1962 David James MP co-founded the Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau with Sir Peter Scott, naturalist and son of Sir Robert Falcon Scott of the Antarctic.

In the 1964 general election, Brighton Kemptown was lost to Labour after a record seven recounts there being only seven votes between the parties.

During the same year, the large family were pictured in The Field. Oddly boxed within an article about shooting migrating gazelle in the 17-mile gap between Fort Leelli and Moranyyuang, a kilted Mr James stood with his wife before his ivy-clad Wivelsfield Green Sussex home behind an unnamed rat-catcher (standing) and a golden Labrador (recumbent). Alongside were his six children; Patsy, aged eleven, Kenny, one and a half, Christopher, six, Michael, eight, Dianna (astride a pony called Delphi), ten, and Peter, twelve.

At the time, their proud father was a trustee of the National Maritime Museum, a council member of the Fauna Preservation Society, Outward Bound Trust and British Field Sports Society.

In 1970 he returned to parliament, this time elected as MP for North Dorset which he represented until standing down at the 1979 election. Also in 1979, he changed his surname to Guthrie-James to mark the connection between Clan Guthrie and his family home of Torosay Castle on the Isle of Mull.

After a brief retirement, he died on 15th December 1986. His widow, the Hon. Mrs James, passed in 2019, aged 91.

Eamonn Andrews shall have the last word,

“David James, this book salutes a vivid figure of the present era whose zestful spirit recalls the gay adventures of the past and sets a bright example to those whose future lies in the New Elizabethan Age.”

David Guthrie-James in 1959,

Walter Bird – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

References & Further Reading

Eric Williams, Great Escape Stories

Fred Brownbill, Navy SEAL death a true tragedy

© AlwaysWorthSaying 202^2

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file