© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2021

Two Rascals

I looked down on a thunderstorm. The distant lights of late evening Manhattan were being complimented. Clouds beneath me luminesced with staccato lightning flashes above a rain-lashed Long Island. 1988 had ended badly. On Wednesday, December 21st a terrorist attack on PanAm flight 103 murdered 270, 11 of whom were in their homes in the quiet Scottish borders town of Lockerbie where the bombed plane crashed. On the other side of the Atlantic, myself and the Dollar wobbled. Travellers were nervous. The airline industry suffered. For the duration, I was becalmed in the United States. Months later, the trade winds had gathered their strength again. I would return to England. Three decades ago, half a British Airways flight a week connected New York’s JFK airport with Manchester. After a seven-hour journey across the Atlantic, it paused at Ringway before hopping on to London Gatwick.

That night the world’s favourite airline, accompanied by thunder cloud turbulence, treated me to an outstanding beef supper alongside a memorable red wine. After the last drop, I relaxed. Still shaken by the previous winter’s tragic events, others remained nervously at home. The Lockheed Tristar (remember them?) was less than a quarter full. I had three seats to myself. Stretching out, my toes touched the aisle. The window touched my head. I folded my still boyish arms behind my neck for a pillow. From this vantage point, I could spy the lone passenger sat behind. And she could spy me. Eyes met. At least one heart beat a little faster.

An elfin face, about the same age as my 26-year-old self, nestled beneath swept-back brunette hair. A young Audrey Hepburn? Better than that. Our ship that passed in the night, the impossible to forget, multi-talented Parisienne Mme Véronique Lindenburg who had been visiting an aunt in New York City.

She asked which sports I played, complimented me on my looks, and puzzled over why I‘d spoilt an attractive combination of dark hair and blue eyes with that transatlantic concoction known as ‘Hairglow’? I was young, it was the eighties. She announced herself an actress. Unprompted, she added that pornography is art. She had my attention.

And she was a pop star. As Berenice, Véronique had a hit single four years previously. Titled an easy to translate Transylvanie, the lyrics told of a parallel but younger self imagined from beneath the grey skies of Paris to a Carpathian paradise. Interesting.

Myself and the French chanteuse got along like an Île de la Cité cathedral roof on fire. But. As if Camus short story conscripts in the Algerian desert, les deux became more intimate then parted. She must give me her number for my next visit to Paris. I hesitated. An iota of a second of a pause means nothing to the brutish Anglo-Saxon male but to the cultured daughter of a Paris Conservatoire professor it alarms to the possibility of a wife or even an unspeakable ‘English pastime’. A special moment had been guillotined.

Four years previous to Transylanvie, Véronique starred in Les Turlupins, titled The Rascals for English speaking audiences. Tired of being groped beneath the table by a frivolous coming of age teenager called Bernard, Véronique playing ‘cousin’ excuses herself from the family meal and takes Bernard and another cousin outside to draw the attention of the frustrated youth to the other girl. Difficult to do on an aeroplane. Plan B (pronounced ‘Buh’ in French) called. As if Sherednadze, or more appropriately Candide on an interminable ocean voyage lashed to a ‘for want of anything else’ monk by a vindictive Voltaire, Mme Lindenberg must distract with an absorbing story. And what a story it was.

The Irascibles

On May 22nd 1950 The New York Times published a front-page open letter from 18 abstract artists addressed to Roland L Redmond, President of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Arts, decrying that establishment’s exhibition American Painting Today – 1950 and refusing to submit their works. In the resulting hoo-ha, the group was labelled ‘The Irascibles’ with a Life magazine Nena Leen photograph of fifteen of their members becoming an icon of what we now know as the New York School. The only woman present, standing on a table at the back behind and to the left of Jackson Pollock, was Hedda Sterne, my companion’s New York aunt.

A photograph of 15 of the so-called Irascibles,

Nina Leen – Fair usage via Wikipedia.org

Born in Bucharest on August 4th 1910 as Hedwig Lindenberg, Hedda’s was a comfortable and cultured childhood as part of a wealthy pharmaceuticals dynasty. Her mother wrote poetry. Her father was a languages teacher. Her brother and only sibling was Véronique’s father, Edouard. Two years her senior, he was a gifted musician. Hedda was educated by, and became a member of, Bucharest’s thriving pre-war avant-garde community. In 1922 she married businessman Fritz Stern, continuing her art studies in Paris and Vienna and specialising in collage.

As dark clouds gathered over Europe, and having witnessed the Bucharest pogrom of January 1941, the Steins left for the United States. Firstly Fritz, followed by his wife in October of the same year. Edouard stayed behind, giving clandestine music lessons to ‘banned’ students, and didn’t leave Romania until after the war. Moving to Paris, he became a conductor and professor at the city’s prestigious Conservatoire. Establishing herself in the New York art scene, Hedda changed her name to Sterne (with an ‘e’) and was part of the groundbreaking and critically well-received 1943 Peggy Guggenheim surrealist Exhibition by 31 Women.

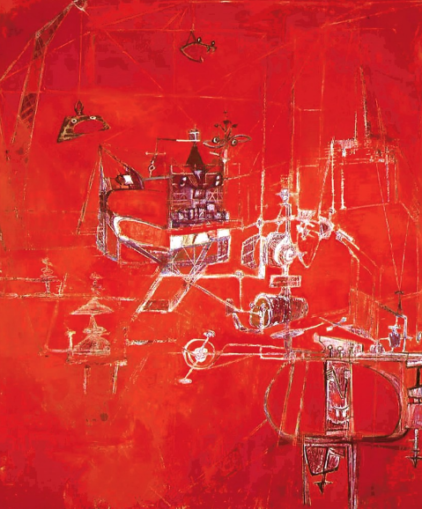

My digital painting after Hedda Sterne’s 1950 oil painting, ‘Machine 5’,

Steve Harlow – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Although Hedda disliked having a style attributed to her work and disliked being labelled as an irascible even more so (maintaining her co-signatories hated her), Sterne’s work although individualistic didn’t exist in a vacuum. The Hedda Sterne Foundation categorises her work, perhaps rather loosely, to portraiture, philosophy and meditation, gestural abstraction, the everyday surreal and automatism.

In a 2011 obituary (yes she lived to be a hundred) The Guardian noted Sterne didn’t have a ‘logo style’ but was rather an uncommitted off and on abstractionist whose work went, unlike most artists, in many directions. Her final exhibition, in 2008, was of line drawings of friends. Close to her passing, as her sight failed, she created white on white works depicting the floaters she saw behind her eyes.

Saul Steinberg

Having divorced in 1944, within months Hedda Sterne had married cartoonist and fellow Romanian refugee Saul Steinberg, a wartime illustrator for the OSS (forerunner of the CIA) and subsequently artist in residence at The New Yorker magazine, responsible for many of the sophisticated weekly cultural commentator’s iconic covers.

Steinberg was born in rural Romania in 1914. After studying at the University of Bucharest, he enrolled at the Polytechnic University of Milan in 1933 complimenting his architectural studies by drawing humorous cartoons. As anti-Semitism raised its head in fascist Italy, he left for the Dominican Republic in 1941. From there he contributed to American publications, including The New Yorker, until a United States visa was granted to him in 1942. Almost immediately he was commissioned to the OSS where his fine eye, delicate hand and acerbic wit was put to use in the Moral Operation (MO) division.

Steiner described one of his roles thus,

In May 1944, the MO group was transferred back to Algiers in view of D-Day France. The activity consisted chiefly in dissemination and organization. The first issue of Das Neue Deutschland was printed there.

The Das Neue Deutschland being disseminated was a black propaganda publication, distributed clandestinely in Germany, seeking to undermine the authority of the Nazis by suggesting the existence of an underground movement about to overthrow Hitler. After the war, Steiner continued to contribute to The New Yorker and other prestigious publications. According to wiki,

Steinberg’s long, multifaceted career encompassed works in many media and appeared in different contexts. In addition to magazine publications and gallery art, he produced advertising art, photoworks, textiles, stage sets, and murals.

SAUL-STEINBERG-1976,

alyletteri – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Saul became a wealthy man. His commission for the Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati can be seen here. And here is one of his works behind the bar of an American Export Line ocean cruiser. A darling of New York artistic society, Steiner became a notorious boulevardier. Hedda and Saul separated in 1960 but never divorced and remained friends until he predeceased her in 1999.

Under the black and white sky of Paris

Having stolen a line from Transylvanie, what of Mme Lindenberg’s journey after that passing night three decades ago?

As early as 1985, Véronique had authored Botte Rouge, a two-hander stage thriller telling the story of red booted Evelyne who receives to her studio a bourgeois woman curious for a moment of pleasure. Made into a TV movie, it starred prolific actress Magali Noel who had been previously directed by Fellini in La Dolce Vita.

In the intervening decades, Véronique advanced her career in film and television; directing, acting, narrating, editing et al.

Her 2010 score for camera short Pattes de Deux was a Chicago Film Festival nominee. Also in 2010, Véronique starred in, narrated and edited Final Girl, an exploration of the menage a quatre and an official selection at both the Tel Aviv and Mix Mexico film festivals. Likewise, comedy crime zombie film Qui de loin semblent des mouches which reprised her Berenice alter ego. Her other editing credits include the successful legal comedy-drama Lebowitz v Lebowitz shown on the France 2 network (a cross-channel BBC1) which regularly pulled 4 million viewers.

More recently, she directed Les Caprices, an adaptation of Alfred de Musset’s opéra comique Caprices de Marianne, and edited and narrated Frassoni and Bouvier’s Leo Ferre, Un Homme Libre, an homage to the Monégasque musician of the title.

As for the friendship with her aunt, in conversation with Nancy Natale and Binnie Birstein of artinthestudio, Véronique recalled first meeting Hedda Sterne when in her mid-teens after the death of her father, Eduardo. Devoted to her art, Hedda had little time for her sixteen-year-old niece but across the decades a strong relationship developed between the two during visits to New York. Eventually, they were to be each other’s only living relative and, after the great artist’s passing, Mme Lindenberg was the obvious choice for Chairperson of The Hedda Sterne Foundation.

Presently, Véronique and the Foundation are promoting yet another of the ever-popular modern artist’s retrospectives, this time Architecture of the Mind at the prestigious Van Doren Waxter gallery on New York’s 73rd Steet. The works are repetitive and remind one of the urban American automatistic built environment which so fascinated old-world migrant Sterne. Symmetrical about both axes, horizons and vanishing points emerge from canvases to disappear into or from the paintings, making a forceful impression but destined never to meet again – as if those two young ships that passed one stormy night.

Acknowledgements

artinthestudio.blogspot.com

The Guardian

Hedda Sterne Foundation

IMDb

Van Doren Waxter

wiki

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file