Dan Davison from Rochford, England, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Operation Barras – September 2000

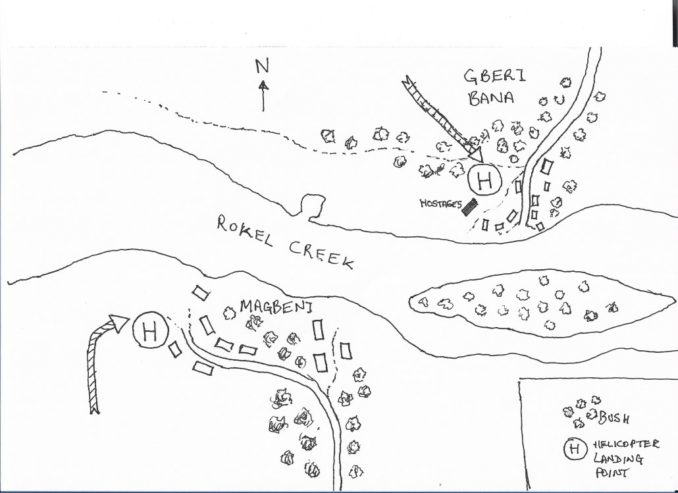

Despite the British military presence in the country, Sierra Leone’s civil war rumbled on. The country would remain important to Britain because of its huge resources of diamonds. The West Side Boys were a militia group who were initially loyal to the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) the rebel organisation opposing the army. The British had used this organisation in at least one operation, directed by military officers, in exchange for weapons and medical supplies. However, the West Side Boys refused to become part of the reconstituted Sierra Leone army and began to operate in the area of Magbeni and Gberi Bana, two abandoned villages on each side of Rokel Creek.

On a typical, West-African day on the 25th August 2000, when the bush was shimmering in the late morning heat, a patrol of eleven men from the 1st Royal Irish Regiment and an official interpreter from the Sierra Leone army left the base, codenamed Waterloo. They were visiting Jordanian peacekeepers attached to UNAMSIL and based at Masiaka. Over lunch the Jordanians told the Royal Irish that the West Side Boys had decided to begin disarming and the Major decided to visit Magbeni to find out for himself. On the way back to the Waterloo base the patrol diverted off the main track to Rokel Creek and near Magbeni, a large force of West Side Boys appeared out of the bush and surrounded the patrol, using an anti-aircraft gun mounted on a Bedford truck to block the patrol’s route. The Major dismounted from his vehicle, then resisted an attempt to grab his rifle and was beaten. He and the rest of the patrol were then forced into canoes at the bank of Rokel Creek and transported to Gberi Bana, a village on the other side of the river, just upstream from the point of the initial confrontation.

With the agreement of the Sierra Leone President, the British started negotiations to free the Royal Irish hostages. The dialogues were conducted by the commander of I R Irish, with a small team that included hostage negotiators from the Metropolitan Police. They were not allowed any closer than the village of Magbeni and were met by the self-proclaimed “Brigadier” Foday Kallay who was leader of the West Side Boys.

On 29th August the British negotiators demanded proof that the captives were still alive and two British officer hostages were brought to the meeting, the Major and the company commander. During the meeting when the officers shook hands with the negotiators, the Captain surreptitiously passed on a note when they shook hands, which contained a map of the layout of the village and where the men were being held.

On 31st August eleven of the hostages were released in exchange for a satellite telephone and medical supplies. The Royal Irish Major had decided to allow the youngest men to be released first but changed this to the married men and those released included the Sergeant Major, two corporals and two rangers. The remainder were told they would not be released until all of the West Side Boys’ demands were met. The released soldiers were flown to the RFA Sir Percival, anchored off the coast, for a medical check-up and debriefing.

The West Side Boys’ official spokesman was “Colonel Cambodia” who used the satellite phone to contact the BBC with a lengthy list of demands, which included the release of all prisoners held by the Sierra Leone government and re-negotiation of the peace accord. During the lengthy and rambling list of demands, “Colonel Cambodia” drained the sat phone’s batteries, but not before specialists from the Royal Corps of Signals had located its exact position.

The West Side Boys were particularly dangerous and unpredictable due to their heavy use of cannabis and cocaine and the released Royal Irish soldiers told their de-briefers that there had been mock executions carried out on the captives. The captors would often forget their previous demands due to their excessive drug use, which also made them dangerously unpredictable. Further demands from the West Side Boys included immunity from prosecution and that they be allowed to attend university courses in Britain.

Around the time that the five soldiers were released, two negotiators from the SAS joined the negotiating team. One of them attended several meetings with the West Side Boys, posing as a Royal Irish major in order to provide reconnaissance and gather intelligence in case an assault was required. Shortly after the patrol’s capture Surgeon Lieutenant Jon Carty RN, the medical officer on board HMS Argyll which was also off the coast, was brought ashore to assess the soldiers, should they be freed, or to provide immediate care in the event of an assault resulting in casualties. Argyll also served as a temporary base for two Army Air Corps Lynx attack helicopters from No. 657 Squadron which had been flown to Sierra Leone to support any direct action.

Planning for a military option to end the hostage situation progressed, it became clear that, given the number of West Side Boys and their separation between two locations (Gberi Bana as well as the village of Magbeni; see below), the operation could not be conducted by Special Forces alone. Therefore, the headquarters of 1st Battalion the Parachute Regiment (1 PARA) was ordered to assemble an enhanced company group, which would support Special Forces if such an operation was launched. The battalion’s commanding officer selected A Company, led by Major Matthew Lowe, which had been on exercise in Jamaica at the time of the initial British deployment to Sierra Leone. Several members of A Company were new recruits who had only completed basic training two weeks prior. Lowe decided that replacing them with more experienced soldiers would risk undermining the cohesion and morale of the company, but several specialist units from elsewhere in 1 PARA such as a Pathfinder section were attached to A Company to bring the company group up to the required strength, including a signals group, snipers, heavy machine gun sections, and a mortar section. The additional firepower was included to maximise the options available to the planners, given that the West Side Boys had a numerical advantage and that additional resources would not be immediately available should the operation run into difficulties.

* * *

On the 29th August 2000, Guy Jarvis was at his parents’ home for his summer leave. It was early in the afternoon and Jarvis was visiting his father, who had been admitted to the Samuel Johnson Community Hospital because he was having difficulty in swallowing food and liquids. He was shocked at just how ill and emaciated his father appeared, as the cancer consumed him. He knew that it had spread to his liver and stomach and both he and his father were aware that he was dying. His mother seemed to be either indifferent or uncomprehending to her husband’s fate and had remained at home.

“How long will you be in here for, Dad?”

His father shrugged. Guy knew that talking was painful, “Till the time comes. It won’t be long now.”

“Oh for God’s sake, Dad.”

“Guy, I’ve always been honest with you. Be honest with yourself. We all have to die someday. At least I have a very good idea when my day will come.”

The man who seemed to have aged overnight, grabbed Guy’s hand with a fierce grip, “I have never told you how immensely proud of you I am. Despite the things you have seen and have been forced to do in order to survive, you have never allowed them to corrode your soul. I know that deep down you are a quiet, kindly and sensitive person, and I can leave this world, knowing that I have left behind one of the most remarkable young men I have ever met. God has been kind to you, Guy. Allow him to be kind to you in the future.

“Goodbye, Guy. My time is near. I don’t think we will meet again on this earth. I will always love you…”

As Jarvis walked across the car park to his car, he suddenly couldn’t see clearly and he angrily rubbed the tears out of his eyes. He leaned against his car and looked up at the sunlight dappling through the trees and then his mobile phone went off…

* * *

As soon as they arrived at South Cerney their mobile phones were taken off them. The cover story was that they were mounting a “Readiness Exercise” and there were assorted members of 1 PARA, about an enhanced company strength and other units with a few members of the RN and RAF. A Company of 1 PARA had been selected to carry out an operation to support the Special Forces and the troops were briefed on their likely mission. The Major commanding the airborne element put his planning team together and much to Jarvis’ surprised he was selected because as the Captain 2IC told him:

“We’ve heard that you’re the expert on Africa, Jarvis and you know the ground.”

“Sir, I’ve only been to Sierra Leone once before.”

“Well that’s once more than me and I believe that you were in Rwanda previously, so guess what? You’re on board whether you want to be or not.”

On 3rd September, the planning team was flown by an RAF jet to Dakar in Senegal to continue planning and study intelligence about the area and the state of the hostages. Covert SF teams were operating in the area, and as the West Side Boys were based in two locations on either side of Rokel Creek, there were insufficient numbers of SF to assault the two locations at the same time. It would take around fourteen hours to mount the mission from the UK, giving the West Side Boys time to kill the hostages, and there was already open speculation in the media that a rescue attempt would be made. The remainder of the company group was flown into Dakar to cut the response time.

Political authority to mount the mission was delegated to the British High Commissioner in Freetown and the operation would be mounted under the command of Brigadier Richards, the military commander in Sierra Leone. By this time the British forces had a good intelligence picture of what was happening on the ground, thanks to SF observations that had been inserted into the area by SBS assault boats. Part of this recon phase was to identify landing sites for the transport helicopters.

1 PARA was tasked with an assault on the village of Magbeni, south of Rokel Creek, to prevent enemy forces from interfering with the hostage rescue, disrupt the West Side Boys and recover the Royal Irish vehicles. Meanwhile the SAS would attack Gberi Bana in order to release the hostages. In the final planning phase, several methods of inserting the assault forces were scoped, including an overland assault by vehicles or by boat insertion. The former was ruled out because it could allow the West Side Boys to react and give them enough time to kill the hostages. The latter was discounted because there were insufficient boats and strong currents and sandbanks in Rokel Creek. It was decided that the force would be inserted by three RAF Chinook helicopters from No 7 SF Squadron and the airframes were already in theatre after Op PALLISER. The transport helicopters would be supported by two Lynx attack helicopters based on board RFA Sir Percivale.

By the 5th September the British media was openly speculating that a rescue mission would be mounted imminently and the arrival of 1 PARA in Sierra Leone as a “contingency” allowed the elements of D Squadron 22 SAS to enter the country unnoticed. A forward operating base was established at “Hastings,” a camp that was around thirty miles south of Freetown.

© Blown Periphery, Going Postal

As Jarvis walked off the rear ramp of the Chinook at Hastings he noticed that in an open area, a series of ISO containers, tents and makeshift huts had been set up. It was a full-size replica of Magbeni village where the troops could practice the techniques for the assault and layout of the area. Jarvis had a feeling of unreality that he, a lowly corporal was part of the planning team with the grownups. The members of 1 PARA went through the assault phase of the operation, while the SAS troops in another part of the camp went through their scheme of manoeuvre. Jarvis soon noticed a problem, which he raised with the Major.

“Sir, we don’t have enough time to acclimatise and some of the boys are showing signs of heat exhaustion. I think we’re carrying too much kit.”

He fully expected to be told to wind his neck in, but the major contemplated the observation. He called for the leader of the SAS team over and they discussed the problem.

“The boys are carrying a lot of ammunition and even with light fighting order, they’re knackered.”

In the end it was agreed that the Paras would go in with just ammunition, first field dressings and two water bottles per man. They also discussed whether body armour should be omitted, but they finally decided that the risk was too great and the body armour would be worn. The operation was planned for early morning, before the temperature became too high, but there would still be limited light.

On 6th September the Director of Special Forces flew into Freetown with his headquarters staff, which included a team from the RAF’s Tactical Communications Wing (TCW). There was a COBRA meeting in London on the same day and the opinion was that the West Side Boys had given up any pretence of serious negotiations, as their demands were becoming more ludicrous, such as forming an entirely new Sierra Leone government. The covert SF observation teams reported that they had seen no sight of the Royal Irish hostages for around four days so the assault was ordered for the 9th September.

There was little sleep the following day and night as the troops were given their detailed, final briefings. Jarvis was invited by the major to brief the assault force, as he had some experience of African troops both in Rwanda and earlier that year at Freetown. He nervously took the stage.

“Don’t kid yourselves that all African troops are crap. Some are, but remember that they know the land and we’re classed as the oppressors. They can fight hard and then suddenly give up, melt away. The worst ones are those that have been taking drugs. Casualties don’t’ matter to them and they will fight with a zeal that you wouldn’t believe. They are the most dangerous. Some of them will be children. They will kill you as soon as blink, so show them no mercy in the firefight.”

It would be the job of Jarvis and the Pathfinders to secure the landing zone for the Chinook, in order to evacuate the Magbeni assault team of the Paras. That afternoon of the 9th September the three Chinooks arrived and suddenly everything seemed so real. For many of the Paras, this would be their first time of going into action. Some talked too loudly and laughed too much at a stupid comment or joke. Some fell into quiet introspection while others were discreetly sick around the back of the buildings.

Jarvis had his familiar friends sitting on his shoulders, the insidious one telling him that he was going into a maelstrom of fire, the one who detailed how it would feel to die alone in the African bush. He called that thought Peter Lorrie. The other he called Jack Hawkins, the one who instructed him how to face the fear, waiting in the wings. How life was one big act and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances, and one man in his time plays many parts. As Jarvis settled into his sleeping bag for what could be his last sleep he watched the brilliant stars above in the purple eternity and thought that he was merely a speck of dust in the endless universe. Sleep was not his friend that night.

They were woken before the sun painted its golden hue on the eastern horizon above the Kangari Hills. Coughing and hawking some ate breakfast while nearly everybody had a mug of sweet tea. The ground crews were fussing around the three Chinooks while the aircrew carried out their checks, then the rotor blades swung into life, windmilling and blowing up fine dust. The Lieutenant in charge of the eight Pathfinders made a final check of all of their equipment. As they had to clear the helicopter landing point. They would be last on and first off.

The helicopters’ engines were running on the line by the time they were organised into their chalks and filed on board. They approached from the rear with their light fighting order, each section of four up gunned with a Minime squad machine gun. The rear loadie made sure they were seated, then went forward to man the port side chain gun. The two Chinooks with the contingent from 22 SAS took off first with the Paras bringing up the rear. In the swirling dust, Guy saw the mock-up of the village they would be attacking. They were on their way to assault the real thing and suddenly Jarvis noticed that his fear had gone. He looked at his hand and the tremble had disappeared, although the mug of tea was still heavy in his stomach. He wished that he had faith to console him unlike his father, but his only salvation were his M16 and 180 rounds of 5.56mm ball ammunition. He risked a look at his fellow Pathfinders and caught one of their eyes, both smiling wanly at each other with a shy smile, like fifth formers at a school disco.

The Chinooks flew very low, following the twisting course of Rokel Creek towards the rising sun. The journey was around fifteen minutes flying time, but after ten minutes the three helicopters went into a holding hover, line astern below the tree line and just above the murky waters of the creek. This delay was to allow the SAS observation teams enough time to move into position. They would prevent the West Side Boys from moving in on the captives and killing them, before the extraction teams were in position. On receipt of a radio message, the Chinooks were on their way again and two Lynx attack helicopters cleared the landing zones with rockets and gunfire and attacked the heavy weapons that the SAS teams had identified.

As they swept in low over Magbeni, Jarvis who was seated close to the ramp, saw the corrugated roofs of the huts blown off by the Chinooks’ massive downdraft. The helicopter reared up, its tail ramp a few feet from the ground at the edge of the creek. The Pathfinders were up and started to jump out of the back of the Chinook. Across the creek, Jarvis saw the SAS fast-roping from their two Chinooks. There was gunfire from the tree line and he was out, expecting to land on solid ground. Instead he pitched forward and went up to his chest in foul-tasting swamp water. They had been warned that the landing area was wet, but not a quagmire and the Paras struggled trying to make their way to firm ground. Jarvis and his team waded to the tree line where they took cover, while the Chinook came back to pick up those still floundering in the swamp.

Heavy rounds thumped and cracked overhead all around them as a heavy machine gun opened up on the helicopter. One of the Lynx strafed the position from which the enemy fire was coming and the machine gun fell silent. The rest of the Paras disembarked on the firmer ground but as the Chinook soared away, a stray mortar round injured the Major and seven of his headquarters staff. The Chinook that had been earmarked to pick up the Royal Irish landed in the track through the village of Magbeni and the casualties were loaded on board, before crossing the creek to Gberi Bana to pick up the hostages. Jarvis began moving from hut to hut, clearing them with long bursts. The training kicked in and he felt no emotion as the West Side Boys were mowed down, many still in their beds. They quickly fanned out through the village, clearing the huts and discovering the enemy’s weapons store and the Royal Irish’s vehicles.

On the north side of the creek the SF troopers immediately came under fire as they fast-roped from the Chinooks. It was during this first contact that a trooper was shot, the round entering his side, leaving him severely injured. He was dragged back to the helicopter for the medical team to work on him while he was flown back to the Sir Percivale. Despite the best efforts of the in-transit medical team and the surgical team on the ship, the trooper died of his wounds, the only British fatality of the operation.

The SAS cleared the village, heavily engaging any resistance from the West Side Boys. They located the British hostages who were shouting: BRITISH ARMY, BRITISH ARMY. The interpreter was more difficult to find, but he was rescued from an open pit that had been used by the West Side Boys as a latrine. He had been badly beaten during his captivity and had to be carried to the helicopter. Less than twenty minutes after the rescue team landed, the hostages were evacuated to the ship, leaving the Paras to secure Magbeni. The operation also freed 22 Sierra Leonean civilians who had been held captive by the West Side Boys. The men were used as servants and put through crude military training by the West Side Boys, possibly with the intention of forcing them to fight in the future, while the women were used as sex slaves. Planners had been concerned that West Side Boys might try to conceal themselves among the civilians and so the civilians were also restrained and taken to the Jordanian peacekeepers’ base to be identified.

There was a sense of unreality among the Paras after the helicopters left and they went into all-round defence to hold the village. They deployed claymore mines and mortars to defend the tracks from the bush into the now ruined collection of huts, a couple of which were burning fiercely. For the first time, Jarvis relaxed and pulled off his helmet. A round had creased the Kevlar outer skin and the material cover was split, the Kevlar beneath it open like fibrous wool. It had been a lucky escape and he never even felt it. The sweat had run through the mud on his face like some ghastly theatrical make up under the limelight. Words were unnecessary. They had come through the other side. The adrenalin was no longer coursing through their bodies and if the truth were known, all Jarvis wanted to do was sleep.

Two Chinooks returned at 11:00 to under sling the Royal Irish’s vehicles and keep the bean counters in Whitehall happy. At around 14:00 Jarvis climbed onto the Chinook, one of the last to leave Magbeni. They were flown back to Hastings to enjoy a meal and two cans each of warm beer that had been on the RFA off Freetown. Jarvis sat in the shade and cleaned his rifle, musing on the day’s events. They would be flown out to Senegal the following day, then back to Britain for a debrief and a well-earned period of leave.

Jarvis had no way of knowing that he had just taken part in one of the classic military operations, involving all three services and the Special Forces. Operation BARRAS would be studied in command and staff colleges around the world, a classic example of military intervention and hostage rescue. A lowly Corporal Jarvis fell asleep to the exuberant whoops of the Paras, savouring their two cans of Carlsberg lager. Guy Jarvis would later find out that his father had died in the hospital at about the same time he was stepping off the helicopter, into the swamp. He would console himself that perhaps his father had been with him, looking after him in spirit.

Now available on Amazon:

And from Matador:

War Crimes for the Political Elite

© Blown Periphery 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file