I’d again like to begin by thanking all those who encouraged me to continue this series in their comments on Part 7. Whilst always welcome there is no longer any need to say so from my point of view as there are clearly enough who are sufficiently interested for me to keep going – at least for the time being. I would though like to thank Roger Ackroyd, Sharpie 301, Tom Pudding and all others who added stories of their own seafaring exploits.

In reply to DJM I say, no, I never did sail into Charlestown in Cornwall though I visited by land with my son and his family a few years ago. We all went in to the Shipwreck Treasure Museum. We shan’t be going back though because the young woman selling tickets thought my daughter-in-law’s request for one of ours to be priced at the Old- Age Concession Rate was for her own entry! I’ve never heard the end of that incident, always told in an indignant voice at full volume.

I also thank Gotham …. (Joker?) for his description of how he released an anchor from the seabed because that gives me an opportunity to relate a non-chronological Yarn from 2007.

AN OUT OF SEQUENCE YARN

A stuck anchor is a common problem that can sometimes be dealt with by means of this device or something similar as described in these tips. In one case, when none of these worked for me, a fellow cruiser with a good pair of lungs capable of free-diving to significant depths managed to extract my anchor from below a flat form of coral with thick plates parallel to the seabed! Some yachties who are also Scuba enthusiasts always have a means of trying to deal with the problem though underwater visibility sometimes creates difficulties.

My own worst experience was when trying to leave the port of Merak in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra. My anchor became trapped by what I finally discovered was a monster one that had been lost or discarded and left on the seabed. I had to hoist them both a few inches at a time with a rest period between stages to let the windlass motor cool down (a 60-70 amp current at 12.5 volts creates a lot of heat in the coils). When I finally got them as high as they could go but still dangling several feet below Alchemi’s bow I could see part of the problem was that the two were locked together by a loop of my chain still under great tension.

I wondered whether I’d have to ask for help but my Indonesian was practically non existent beyond knowing that Orang Outan means “Man of the Woods” and Nasi Goreng and Beef Rendang are tasty local dishes. Eventually, I was able to solve the problem by attaching a halyard to the monster and using a winch to hoist it high enough to slacken and disengage the chain. I just returned the monster to the deep and hoped no one else would have the same experience. I think its unlikely any-one did because only very few yachts cross the North Indian Ocean by that route, past Krakatoa and via the Chagos Archipelago before reaching the Seychelles and Madagascar. Most go by the conventional route from Langkawai via Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

MAIDEN VOYAGE

Ownership of the Yacht Sales and Charter business that held the agency from Pacific Seacraft changed during the period between my initial enquiries and taking delivery of Alchemi.

The original owner was an enthusiastic sailor with his own yacht who had cruised extensively around the Cornish Coast for many years. In my early discussions with him I had half-jokingly asked – “If I buy a yacht from you, will you Pilot a maiden Voyage to the Scilly Isles?” – to which he replied “OK, you’re on”. I reminded him of that after I had taken delivery of the yacht and he, my youngest son and I, undertook the voyage at the end of June 1996.

This was significant for me because the Scilly Isles are a notoriously difficult sailing area of low-lying islands, rocks, shallows and fast currents upon which there have been many shipwrecks. I wouldn’t have attempted to sail there on my own at that stage of my development as a mariner.

AN HISTORICAL SHIPWRECK

Perhaps the most notorious wrecks were those of ships in the Naval Fleet commanded by Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell, returning home after a successful campaign at the siege of Toulon in 1707. There were 21 ships and two other Admirals in the fleet that experienced bad weather for many days before reaching the area. Four of the largest were lost with the number of men who died being estimated at somewhere between 1,400 and 2,000 including Shovell on board his flagship “Association”.

There was no GPS in those days of course and the charts of the area were unreliable because cartographers didn’t have accurate surveys from which to work. On top of that visibility had been poor and the seas rough making it difficult or impossible to take accurate sights by sextant. Navigators in the fleet had to estimate where they were by “Dead Reckoning”.

That is a pretty approximate process in the best of circumstances and in this case it was later found to have been made even more inaccurate because most of the compasses in the fleet had not been calibrated for a long time.

A consequence of all this was many differences of opinion amongst the Navigators about the position of the fleet. One Captain correctly judged they were not far off the island of St Agnes but Sir Cloudesley and the other two admirals concluded they were about 100 miles south and 50 miles east of that, near Ile d’Ouessant at the end of the Brittany Peninsula (known as Ushant by the English). The fleet was accordingly ordered to continue sailing east-by-north and soon after ran onto the numerous rocks on the south-western side of the Scilly Isles.

It is sometimes believed the Longitude Act of 1714 announcing a Monetary Prize for the first person to discover a simple and reliable way in which to establish longitude at sea was passed as a result of this disaster but it’s worth noting the mistake about longitude was only about one half of that in latitude.

Many people will have read Patrick O’Brian’s stories of Captain Aubrey who used the ideas of Classical Astronomers’ of the era to determine longitude. Those were based on taking observations of the Moons of Jupiter, but that was hardly a simple and suitable method for every-day use by observers on a rocking and rolling ship at sea.

Dava Sobel recounted in her book “Longitude” published in 2007 the way the challenge was eventually met by John Harrison who designed and built a series of clocks with ever-improving corrections for movement, temperature and humidity changes.

Accurate time-keeping, together with tables recording the sun’s altitude at Greenwich noon was the key because the difference in hours between shipboard Greenwich time at local noon and Greenwich noon on the same day taken from the almanac, divided by 24 hours, is the fraction of 360 degrees that determines longitude.

Harrison never did receive the full prize though. The Elites of the era must have been just as careful to maintain their wealth and privileges as ours are today.

ALCHEMI’S RECORD KEEPING

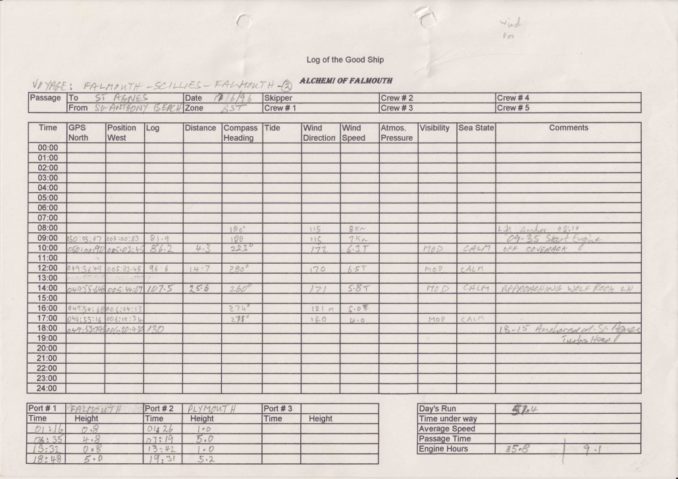

When preparing this article I found my original log sheets in a number of lever arch files at the bottom of a bookcase. I’ll illustrate the way in which I kept records of all my sailing days using the logsheet for the second day of this maiden voyage. On Sunday we merely sailed from Falmouth Marina to an anchorage off the beach at St Anthony’s Head in order to get a good start on the following day.

The format made provision for all six of Alchemi’s berths to be occupied – 2 in the forepeak, 3 in the main cabin and 1 in the quarter-berth. In practice, the largest number ever on board at the same time was 4 and that was overcrowded.

There was space to enter tidal data from an almanac at bottom left and in this case we entered the data for both Falmouth and Plymouth because that meant we could estimate depth at any secondary location on our voyage from information already to hand.

In the lower right hand corner there was space to record the day’s overall performance and engine usage.

FALMOUTH TO ST AGNES

The entries were generally made in pencil and are rather faint in this reproduction but you may be able to see they are equivalent to a narrative form that might read :-

- Hoisted anchor at 08:10 and set sail.

- Took two hours to cover 4.3 miles so switched to motoring.

- No wind all morning so still motoring as we approached Wolf Rock at 14:00

- Anchored in Turks Head Bay on St Agnes at 18:15.

Trinity House is the name of the organisation which maintains and operates all lighthouses around the UK. Their website describes how Wolf Rock Lighthouse was finally built in 1869, 80 years after it was first conceived and 75 after initial efforts were destroyed by storms. It also mentions this snippet of information:

The lighthouse achieved worldwide publicity in 1972 as the first rock lighthouse to have a helideck constructed on top of the lantern housing.

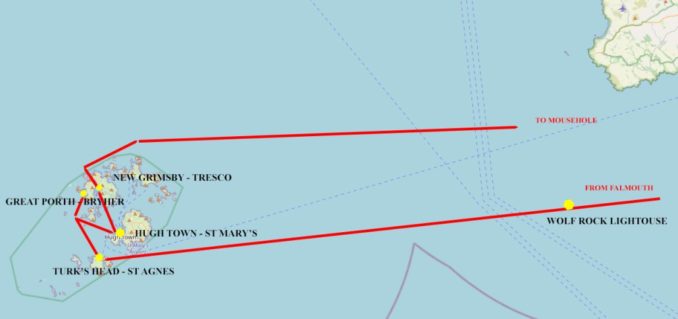

The lighthouse is located about 8 miles off Land’s end and 18 miles east of the Scilly Islands as shown on this map of our outward voyage.

Copy of Open Street Map licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 in accordance with these terms.

ST AGNES TO GREAT PORTH BAY ON BRYHER

From St Agnes we went to Great Porth Bay on Bryher which was only 10 miles away and although the winds were still very light we did manage to sail part of the way.

The notable thing about this destination is that it has a complex approach through rocks and only a small pool in which to anchor. Consequently the scope of the chain has to be much less than the recommended 5 times depth. It would be untenable in strong winds and as our Pilot told us – “Not many Yachts anchor on the West Coast of Bryher”.

GREAT PORTH BAY TO NEW GRIMSBY HARBOUR VIA HUGH TOWN

The next day saw us go first to St Mary’s to pick up a Mooring in the main harbour at Hugh Town which is well-protected by a Breakwater Wall on the western edge. Here we had to wait a few hours because our next destination was New Grimsby Harbour in the channel between Bryher and Tresco and that required passage over an area that is very shallow and can be crossed by a deep keel yacht for only a limited time on either side of high water.

Once across the shallows the depth is OK again at all states of the tide but the channel between Tresco and Bryher is narrow. In common with many other similar configurations around the world a narrow channel and a high tidal range combine to give very high currents since the depth of water is different at each end of the channel for much of the time.

That is why moorings are usually safer than anchoring when near such a configuration (provided the mooring is securely fixed to the seabed and the rope and attachment to the buoy is in good condition). They do have a disadvantage though because when the tide changes direction the boat needs to change from the upstream position in which it finds itself to its new downstream position. That results in a horrid transition period when the buoy bangs against the hull and can even cause damage if it has a tall metal pole at the top to make it easier to reach from the yacht’s deck.

We didn’t go ashore during this visit but I returned to the Scilly Isles and New Grimsby Harbour several times on later occasions and did so once or twice then. I don’t want to say too much about Tresco in this article but neither do I want to later write about shipwrecks. Suffice it to say here that there is an open air Museum on the island at which are displayed figureheads of several wrecked ships that have been recovered from the seabed and restored to their original appearance. The gentleman in this photo was my sailing companion in 1997 who joined me on the last leg of my cruise that year on passage from Bangor in Northern Ireland to Falmouth.

NEW GRIMSBY HARBOUR TO MOUSEHOLE

Our return to Falmouth is illustrated on this map.

Copy of Open Street Map licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 in accordance with these terms.

We left New Grimsby heading north and had sufficient depth in the channel until being able to turn east between the Scillies and Lands End. Thence it was not far before rounding the headland and going to Mousehole on the western side of Penzance Bay. Mousehole is a quaint Cornish village whose name the locals pronounce in their very special way that sounds like something between Muzzle and Mowzel. Its small harbour dries out at low tide but there is an anchorage outside that is usually well sheltered in mid-summer.

MOUSEHOLE TO FOWEY

We had the best sailing of the entire voyage on passage from Mousehole to Fowey with following winds between 15 and 25 knots in the afternoon.

The visitors pontoon at Fowey is very busy in summer and on this occasion so much so that we had to go alongside another yacht already moored to it and “raft-up” by tying ourselves to our neighbour with the normal breast lines to prevent outward, and spring lines to stop parallel movement, relative to the inner boat. When “rafting-up” one additionally attaches two long land-lines that are left slack to the pontoon fore and aft as an ultimate safety precaution. They are also useful if the inner boat wants to leave before the outer one.

FOWEY TO FALMOUTH

The southerly winds had dropped by the following day and we motored most of the way back to Falmouth over a calm sea.

Thus ended a successful maiden voyage during which I learned a great deal and developed sufficient knowledge of the Scillies to give me the confidence to go there without a Pilot on later occasions – though I never again anchored West of Bryher.

To be continued ……….

© Ancient Mariner 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player