Here is a Cabin Announcement. Please fasten your seatbelts, our Time Machine is about to land at Stavanger, Norway in Late July 1997.

I have again made extensive use of my journal when preparing this article so please bear in mind my description is now nearly 25 years old. Some things may still be similar but others will certainly have changed. I have included digitised copies of several prints from my film photos of the time but again ask you to recognise their quality has been degraded by processing and uploading them for display on GP.

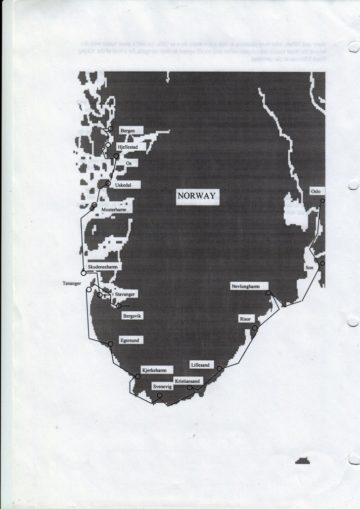

Here again is the planning map for the Norwegian leg of the cruise and we are now about half way up the North Sea coast from Lindesnaes to Bergen.

STAVANGER

The main Yacht Haven in Stavanger is right in the centre of town. This is very convenient for shopping and seeing the sights but rather noisy – as we found out that night when the local youth were having a rave-up in a nearby disco and many residents and visitors were promenading on the quay.

Stavanger is notable for having the largest collection in Europe of wooden houses from the mid-nineteenth century. In the centre of this area there is an old canning factory that has now been converted into Norway’s only Sardine Museum!

Despite it’s rather everyday sort of subject it was in fact pretty interesting with displays of dryers, smokers, can-making machinery and trays in which the cans were placed and hand-packed. Apparently that method is still used (in 1997) since no machine has yet been invented that can do the job better than the human eye and hand.

On an upper floor were the Directors’ and other offices now containing Poster Art used in late 19th/early 20th century marketing and can-wrappers. Down below we found the inevitable tins of sardines for sale and Alchemi’s stores were soon supplemented with several varieties of King Oscar’s best.

I add as a modern note that yesterday, for old times sake, I bought some of the same from my local supermarket, even though I preferred the cans and wrappers from 120 years ago – I think the recipes used to flavour the oil are the same though.

On the quay by the yacht haven there is a large fish stall and for the next couple of days we enjoyed marvellously fresh and tasty prawns, crab and monkfish.

The centre of modern Stavanger is laid out like the spokes of a wheel with two concentric rims lined with shops selling, among other things, beautifully patterned Norwegian Sweaters.

For the first time since leaving Kiel we saw another British Yacht arrive in harbour. John and his crew had sailed from Lossiemouth and were planning to go down the coast up which we had just come. John offered the services of one of his young crewmen to climb Alchemi’s mast to look for the source of a countersunk bolt that had mysteriously appeared on deck. By the time he visited a day or two later I had already done the job myself. I found no explanation for the bolt but did discover and replace a loose shackle securing the staysail to the top of its furling gear.

Another visitor on Saturday was an elderly American Gentleman from a cruise ship that had docked overnight. He recognised Alchemi as a Crealock built by Pacific Seacraft and turned out to have been the owner of Hull Number 34 built by the company in 1981. That was one of their very first 37 foot boats produced before the 34 footer had even been designed. He couldn’t stay long but we enjoyed his visit and enthusiasm.

SKUDENESHAMN AND MOSTERHAMN

Fearing Saturday night discos might be even noisier than Friday ones we left in the afternoon for a glorious sail in a stiff breeze to Skudeneshamn on the southern shore of Karmo Island.

The harbour approach required considerable caution with many rocks awash on both sides and a final entrance whose width was reminiscent of the Blindleia. Once inside we thought at first we’d need to find room near a Najad moored against a concrete wall.

Before doing so we were approached by a local in a small motorboat who advised us to go farther up the channel and after following his directions we found ourselves in one of the smallest and best protected harbours we had visited.

Shortly after we were settled Jan and May Fjermedal visited. They were the Norwegian owners of Fivreld (Butterfly), the Najad we had passed on the way in. They had just returned from the far northern Lofoten Islands (during the best summer in living memory) and planned to cross the Atlantic next year after sailing down the coasts of France, Spain and Portugal to the Canary Islands.

The next section of our voyage found us motor sailing into winds of 25 knots or more in moderately rough seas before being able to turn into the Bomlafjorden and once again sail over relatively calm water in a moderate breeze to Mosterhamn.

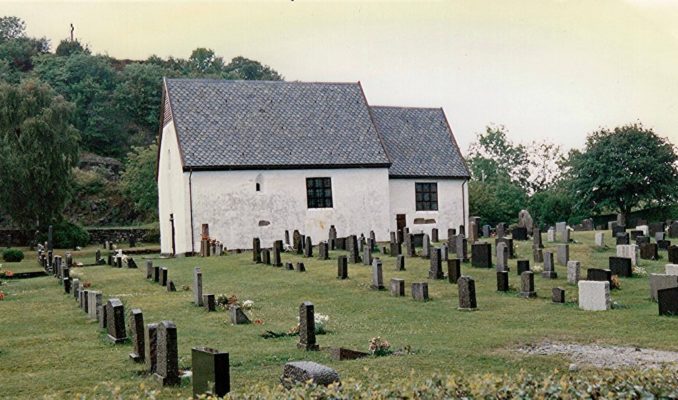

This is another small village with a good harbour notable for its possession of the oldest stone church in Norway.

MORE FJORDS

Leaving Mosterhamn we entered wide fjords in picture postcard Norway. Across perfectly calm water 1,500 feet deep we could see mountain tops nearly 4,000 feet high intermittently covered in cloud with snow on their tops and waterfalls tumbling down their steep sides.

All berths in the small marina at Uskedal were already occupied and we had to moor to a concrete quay with our trusty ladder as a fender-board. Here, I was alarmed to find the depth sounder recorded a highly variable depth over a short measurement period but satisfied myself we would remain afloat with a makehift sounding lead constructed from a bit of rope and my Swedish mooring hook.

There is a narrow stretch of water on the approach to Lukksund that winds its way between high and fir-clad hills on the mainland and the island of Tysnes on the other side. Until recently the island had been accessible only by ferry but there is now a road bridge and power cable spanning the sound. Both lay far overhead as we passed beneath without difficulty.

Once through the sound it was only a short distance across the fjord to the small town of Os. This is only about 20 miles from Bergen by road but about 40 by sea and is really just a dormitory town for the city. There has been much recent construction and we found it rather soulless in comparison with the communities through which we had previously passed.

Water near the so-called marina was very shallow so we moored against tyres on the ferry boat quay with the ladder again in use as a fender-board but struggling to hold position because of wake from passing small craft.

There was a notice on the quay, in Norwegian of course, and a man standing beside it. Here I made a complete fool of myself by asking in carefully enunciated English –

“Ex-cuse me do you know if there is a ferry due overnight?”

To which enquiry I received the reply –

” I dunno mate, I don’t read Norwegian”

The man turned out to be a Pilot for the Port Authority in Southampton invited to stay in Norway by the captain of one of the high-sided Car Transporter ships that regularly deliver Volvos for sale in the UK!

HJELLESTAD

Wednesday was another fine day and with the help of a 15 – 20 knot easterly breeze and calm water we sped through yet more magnificent scenery to the small town of Hjellestad.

There was a proper marina here with floating pontoons and the following morning the water was exceptionally clear. That had a somewhat alarming consequence that led to my next practical lesson in yacht maintenance.

I could see the sacrificial anode at the rear of the propeller was missing altogether. In this design they are conical pyramids of lead, perhaps a couple of inches in diameter and a bit less in height, secured to the end of the propeller shaft by three bolts having an Allen key recess at their end.

As I realised later, the engine is a major component in a yacht’s electrical ground system and is connected directly to the batteries by especially low-resistance cables to make starting easier. Even though there are many interfaces with small air gaps there is thus a direct path between the batteries and the propeller at the end of its shaft. An anode wrapped around the shaft or bolted to the propeller is gradually eroded away by electrolytic action – it is of course placed there deliberately so the erosion occurs in an easily (?) replaced component rather than an expensive piece of machinery.

In designs with an anode bolted to the propeller there is a relatively narrow ligament between the outer edge of the bolt holes and the outside circumference of the pyramid. When that ligament has been eroded away on one bolt hole it won’t be long before the other two suffer as well and soon the rest of the anode is free to go its own way even if it’s only partly worn. The speed at which that happens depends on many different variables but Alchemi’s anode had last been replaced before she left Falmouth several months earlier.

Replacing the anode is a doddle when the yacht is out of the water but here I was with Alchemi in a marina in Norway with no facilities to organise that and a time-table to keep for the planned crew-change in Bergen. What to do?

On with the dry suit again and duck underwater to see the anode is indeed missing but the three bolts are still in place. Many dives later the three bolts had been retrieved without losing either them or the Allen Key. That was more by luck than judgement because it once dropped from my grasp but fell and stayed on top of two propeller blades that happened to be horizontal at the time – whew!

The most difficult part of fitting a new anode was getting the first bolt’s thread engaged, thus securing the anode loosely, without dropping it, the bolt or the key. That required the use of both hands.

I found I could make them available to do that by bracing my feet against the side of the pontoon and holding my head and trunk in position underwater against the hull of the boat at a downward facing angle of about thirty degrees. I could hold that position for about a minute before needing to surface for another breath of fresh air – attaching an air tube to my snorkel mask didn’t help because it just got in the way or filled with water.

That technique eventually allowed me to get the first bolt started and then it was relatively easy to insert the other two and tighten all three.

It is sometimes said that experience comes from bad judgement and knowledge from bad experience.

I learned the hard way that Alchemi’s anode needed to be replaced at least once every six months she was in the water and more frequently if there were stray currents from other sources – as there often are in marinas with shore-power on the pontoons.

TALL SHIPS

Trade was just as competitive in the 19th Century as the 20th and the best return was achieved by companies who could get their products to market quicker than others. Those conditions led to the development and use of Tall Ships for the transport of large and heavy loads by sea.

Although some early coal-fired ships with piston driven engines were pretty fast the displacement of sail by coal and other fossil fuels didn’t happen in a big way until after 1884.

In that year Charles Parsons shocked the Admiralty by launching a boat – Turbinea – at the most prestigious event of the year – the Spithead Review – she was much faster than anything the Navy had and easily evaded picket boats sent to arrest her. She was able to do that because Parsons new invention of the steam turbine engine was so much more effective than piston-driven ones (mainly due to fewer moving parts and because the direct conversion of latent energy in the fuel to mechanical rotation does away with the need for cranks, flywheels etc required to convert linear into rotary motion).

The use of sailing boats for the carriage of goods took a hard knock after Parsons invention was adopted widely, first for Naval Vessels and later for Commercial ones. Oil extraction from the ground and it’s use for many purposes including transport developed rapidly in the first half of the 20th Century and after WW II the use of Tall Ships for commercial purposes had practically died out altogether.

But, in 1953, a retired solicitor in London had the idea that racing them against one another with crews of young people would be a great way of introducing them to adventure and teamwork. The Portuguese Ambassador to London at the time was an enthusiastic supporter of the idea and between them they organised the first Tall Ships Race from Torquay to Lisbon in 1956. (As with the Suez and Algerian Crises, I was only dimly aware of this at the time and was in any case fully occupied by study, cycling, mountaineering and sports of various kinds.)

The first race attracted many other sponsors and participants and here’s a link to the British Pathe site that has a short but great film of the start. The event was so popular the idea was taken up enthusiastically all round the world between 1956 and 1978 when the races became annual events. Between 1973 and 2003 they were sponsored by the owners of the Cutty Sark scotch whisky brand, introduced in 1923 and named after the Scots-built Tea Clipper on display in Greenwich, that was itself built on the Clyde and named after the scots words for “Short Skirt”. This Wikipedia page lists the routes for all the races since 1978.

In 1997 the route was Aberdeen-Trondheim-Stavanger-Gothenburg but the racing only took place over particular stages with the ships sailing in company between one stage and the next. During our stay in Stavanger there had been a bit of a buzz about the anticipated arrival of the fleet after a cruising passage from Bergen . One of the evening rave-ups had been enlivened by a crowd on the quayside cheering on a young man rowing a dinghy across the town-centre harbour he’d named “The F…y Sark” that had a fully inflated sex doll perched high in the stern. The crowd thought that was great fun and since the mood was one of innocent enjoyment the incident had no air of menace or bad taste that might have existed at other times and places.

BERGEN

We therefore had an inkling of what to expect before we reached our northern destination.

Even so, the sight of so many Tall Ships in the same place at the same time was truly astonishing.

It was difficult to find a berth but we eventually rafted up on the unfashionable side of the harbour against a smaller yacht from Germany and in front of a raft of two Scottish yachts, one from Nairn and one from Shetland.

Along with hundreds of other sightseers we walked around the harbour in the evening to gaze at the Ships and their Crews. The size of the ships and their equipment made it seem everything was happening in slow motion but the basic requirements are the same as those for a small yacht. A few were leaving. One or two had tugs to pull them clear but the majority used their engines and a warp tied to bow or stern to “Spring Off” in exactly the same way we do on Alchemi.

Friday was a lazy day but in the evening we completed our transformation into regular tourists by joining an organised coach trip to a small town called Fana to see and hear a folk troupe performing traditional dances and songs. The highlight of this expedition was a side-trip to a twelfth century church in which a soprano with a beautifully modulated voice sang ancient songs of joy and sorrow.

The rest of the evening was a rather disappointing anti-climax in a specially constructed “Mock Farmhouse” where we were served Norwegian porridge made with sour cream and semolina accompanied by dry and unleavened bread!

Nevertheless, we all three reckoned we’d had a pretty successful and interesting trip from Oslo to Bergen.

To be continued …………….

© Ancient Mariner 2021