With all the fuss surrounding the marking of the centenary of the End of War to end all Wars, one name was sadly missing from most reports. Step forward one Fortunio Matania. Who he? Draw closer to the screen, gentle Puffins, set yourselves down, and listen to the story of probably the most famous & popular illustrator of the Great War. Mr Matania was, without doubt a genius in his field. It seems somewhat incongruous that he should now be effectively unknown. Perhaps that is at least in part because the art establishment considered him to be “merely” an illustrator, & as such not a proper artist. It may also have something to do with the fact that Matania was born Italian, proudly retained his Italian passport, was an official War Artist in the first World War & internee in the Second.

© DJM, Going Postal 2020

Yet such was his talent that throughout the 1914-18 conflict his work was featured in every edition of “The War Illustrated ” (the essential magazine read for every household) which brought the narrative of the conflict back to the home fires. Some of his pictures seem now to be from an earlier age – as indeed they are – highlighting events from over one hundred years ago. In the Spring of 1915, Matania made the first of his visits to the Front, arriving just after the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. One of his first trips was to the battlefield where he observed the tragic reality of soldiers bodies alongside everyday litter & refuse. Recounting the experience years later in an interview, he described how he was led by a guide, but had to dive for cover to avoid shellfire where he continued to sketch – this was the basis for his oil painting “Neuve Chapelle 1915” which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1918. To further aid him in recreating the scenes he had witnessed, he dug a trench in the garden of his home back in Potters Bar, & engaged models, dressed in British & German uniforms to pose for him in attitudes of combat, much to the consternation of neighbours & passers by. Matania was also supplied with weaponry by the War Office, including a machine gun, four revolvers & ammunition. Over 20 years later he was summoned to Marylebone Court under the Dangerous Firearms Act of 1937, when it was discovered he was still in possession of the cache….

We must remember that although we look at the illustrations as art, at the time the pictures were indeed, with their accompanying text, “merely” illustrations. Their purpose was to show the conflict to the general public, a conflict so far outside any previous experience that it was difficult for the protagonists to rationalise, let alone those who had no direct experience of it. The pictures & text were the lens through which the general population formed their impressions of the war. They are pictures which try to be factual, but like war coverage of any conflict before or since, they have a secondary propaganda value. They invariably show the Allies to be brave & magnanimous in victory, glorious in defeat, & always kind to animals, young children & old people. The dastardly & beastly Hun was shown in a less kind light.

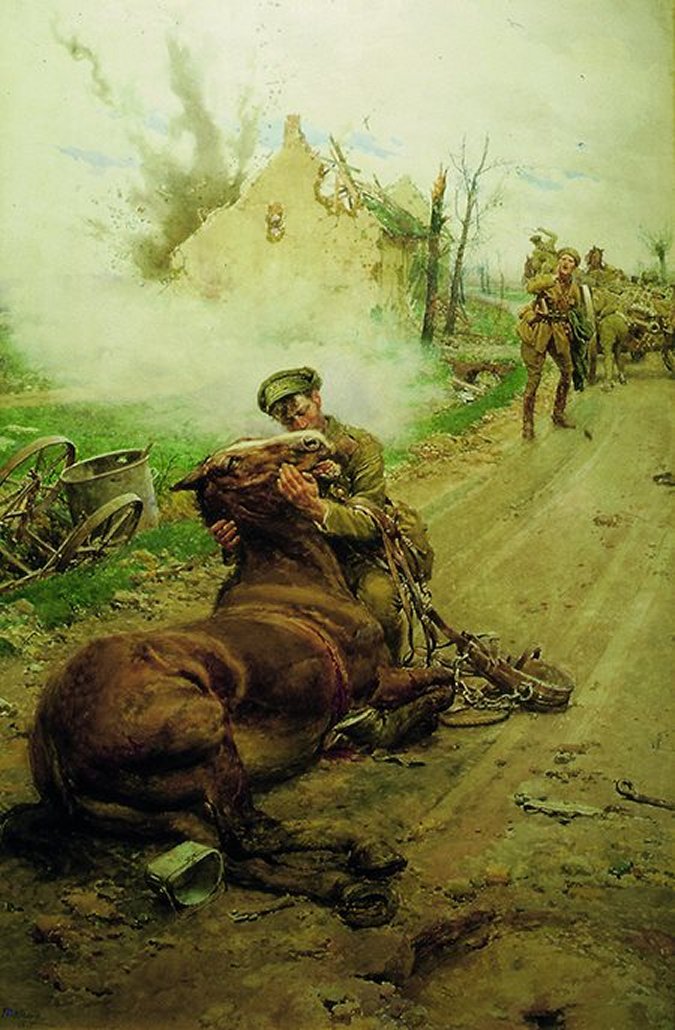

As a young child I was taken – somewhat unwillingly – most Sunday afternoons to visit my maternal Grandmother. She always struck me as a terrifyingly old lady, always dressed in black, who seem to regard my visits as somewhat of an inconvenience & imposition. Looking back, she would have been in her late 60s then, an extremely severe woman, old before her time, having lost her first husband & four other family members in WW1. Her chair – no one else would dare sit in it – in the afternoon sitting room, faced a wall decorated (OT will be pleased to note) with an unremarkable flock wallpaper on which hung the Matania print of June 1916 entitled “Goodbye Old Man” which depicted an incident on the road to a battery position in Southern Flanders. The illustration itself was (I now realise) put out in an effort to distract (AKA gaining control of the narrative) the British general public both from the truly horrific casualty lists that were being regularly released & to dampen hopes that, this time, it really would all be over by Christmas. In the picture – an unapologetic paean to the bond between man & beast – a soldier is saying a reluctant and sorrowful goodbye to his fatally wounded companion as a fellow soldier nearby urges him to leave. This print – and tens of thousand others like it – was used as a fundraising tool & hung in homes throughout the land, sometimes it was the only connection with The Great War that many families could bear to have on daily display after the cessation of hostilities..

Fortunino Matania 1916. Watercolor. Blue Cross Animal Hospital, Victoria, London. (Public Domain)

RIP Jeanetta May Pike

© DJM 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player