Introduction

On Saturday 10 June, 1944, while heading north towards Normandy to help counter the Allied D-Day invasion, German troops of the Der Führer Regiment of the SS Panzer Division Das Reich, committed an unthinkable atrocity in a small village in the Haute-Vienne department in the Nouvelle Aquitaine region of France when they murdered a total of 642 men women and children. The reasons for the massacre remain unexplained to this day.

I can no longer recall exactly when and where it was that I first read about Oradour-sur-Glane but I do remember quite vividly being haunted by the picture of Doctor Desourteaux’s Peugeot 202 slowly rusting away in the main square of the village surrounded by burned out houses. I vowed that one day I would go to Oradour and see for myself the martyred village that, on the post-war orders of General De Gaulle, was to be left preserved in its ruined state as an eternal memorial to those who had died in the atrocity.

Daily life in Oradour

Prior to the massacre, Oradour was a typically peaceful Limousin village, a small town really, whose economic life was enhanced by a tram link to Limoges enabling villagers to commute to comparatively well-paid jobs in the city which is famous for its porcelain industry. According to former residents, it was a pleasant and prosperous village with numerous cafés and restaurants and three dance halls where the young people would meet. There were originally three schools in the village (infants, girls and boys) but in late 1940 a fourth school had been built to accommodate the children of refugees from Charly in Lorraine who had been evicted from their homes by the Germans. The village enjoyed a reputation as a welcoming place and as such attracted refugees in search of a safe haven, including some Jewish families.

Resistance activity in the region

Following the D-Day invasion of 6 June 1944, the Resistance had stepped up its attacks on the Germans in order to frustrate and delay their move northwards to Normandy. There was never any question that, outnumbered and outgunned as they were, they could ever stop the Germans but very much as a few wasps can ruin a barbecue, by constantly shooting at the troops and carrying out various acts of sabotage they set out to create as much confusion and delay as possible.

On 8 June, the Resistance attacked the German garrison at Tulle and very nearly succeeded in liberating the town. They were prevented only by the arrival of Das Reich who, finding that garrison soldiers who had surrendered had been killed and mutilated, arrested 120 Resistance members and proceeded to string them up from lampposts. It was only due to their running out of rope that 21 of the condemned were spared this fate and instead were transported to labour camps in Germany.

The next day and in two separate incidents, two high-ranking German officers Helmut Kämpfe and Karl Gehrlach plus the latter’s driver were captured by Resistance fighters. Kämpfe and the driver were both killed but Gehrlach managed to escape, reporting back to his superiors in Limoges that he had first been taken to Oradour-sur-Glane before being taken elsewhere to be shot.

Around this time the Resistance had also blown up a railway bridge at St Junien only 10km from Oradour killing two German soldiers in the attack and it has been suggested that these events combined may have been the reason why Das Reich decided to teach the Resistance a lesson. This however is speculation.

The events unfold

14:00 Saturday 10 June, 1944

Shortly before 14:00, while the unsuspecting villagers were still enjoying their midday meal, an SS convoy of cars, half-tracks and lorries drove into the Champ de Foire (fairground or main square) in the centre of Oradour and troops were immediately deployed to seal of the roads leading out of the village. According to locals who survived the slaughter, few Germans had been seen in this area of Vichy France since the outbreak of the War so hardly anyone was unduly alarmed.

The mission commander Sturmbannführer (Major) Adolf Diekmann summoned the mayor Jean Desourteaux, a retired doctor, and informed him that an identity parade was to be called. The mayor sent out the town crier who, accompanied by an SS trooper, banged his drum and told everyone to gather in the Champ de Foire with their identity papers. No exceptions would be permitted. It was at this stage that a few young men decided to drift away across the fields thereby saving their lives. Others who feared being conscripted into the feared STO or Service de Travail Obligatoire, a forced labour organisation, hid themselves as best they could. Around 20 people managed to avoid being taken and eventually escaped from the village after nightfall.

The Germans set up a number of machine guns on tripods to cover the square which was standard SS procedure for handling large gatherings of people in the open air. It was when the SS began to clear the Lorraine refugees’ school (Saturday was a school day in 1944) that one pupil, seven-year-old Roger Godfrin had a miraculous escape. While his teacher was talking to a soldier he ducked into another room, climbed out through a window and started to run across the fields. When a German soldier saw and shot at him, young Roger feigned death even while being kicked in the kidneys. After seeing another would be escaper shot and killed, Roger got to his feet and ran towards the River Glane accompanied by a dog called Bobby. Unfortunately they were spotted by troops in a half-track who fired at them. Roger was unscathed and managed to cross the river to safety but the dog was killed. Afterwards Roger said that it was the shooting of the dog that upset him most about the events of the day even though he had lost his entire family in the massacre.

14:30 Saturday 10 June 1944

Meanwhile, villagers were still being assembled in the fairground ostensibly to have their papers checked although at no stage did this happen. Only one person was asked for his papers that day and that was Doctor Jacques Desourteaux (the owner of the Peugeot that I mentioned earlier) when he returned to Oradour in his car after visiting a patient in a nearby village. As his papers showed him to be from Oradour he was told to join the others on the Champ de Foire.

15:00 Saturday 10 June 1944

By now the gathering together of the inhabitants was complete and it is estimated that, together with men from surrounding villages who had made a special journey to Oradour in order to collect their meagre tobacco ration, there were around 650 people of all ages in the square.

At this point the women and children were separated from the men. The Germans now announced that they had information that arms were hidden in the village and that while they were conducting the search, the women and children must go to the church. As they were marched off, the children were encouraged to sing, doubtless to allay any fears they or their mothers might have. One eye-witness later described how the sound of the children’s wooden shoes on the cobbles as they walked to their deaths in the church haunted him.

15:30 Saturday 10 June 1944

According to 19-year-old Robert Hébras, one of only six people who survived the massacre, the mood among the men who were now made to line up in three rows was light and jovial. They didn’t know that the Germans were SS as their insignia was covered by their camouflage smocks and as many of them spoke French and were laughing and joking, there was no apparent cause for alarm. When they were told to turn round and face the wall however with machine guns trained on them, the villagers began to fear the worst. No one knows why they weren’t shot there but it is assumed that disposing of the corpses would have presented major problems and that incineration would be a more effective solution.

The men and boys were then divided into six uneven groups and marched off in different directions. Hébras says that he assumed they were to be locked in barns while the search for weapons took place. His group which comprised about 60 people was herded into Laudy’s barn which was used to store carts and bales of hay. The men were ordered to clear some space inside while the Germans set up a pair of machine guns in the doorway.

16:00 Saturday 10 June 1944

Suddenly, upon the sound of what Hébras took to be a grenade exploding, the machine guns started firing and the dead and wounded fell in a heap. It has been suggested that the Germans deliberately aimed low so as to injure rather than kill their victims outright as one victim who had lost a leg in the previous War shouted, ‘Ah, the bastards! They’ve cut my other leg off!’ Hébras was at the bottom of a pile of bodies and describes not knowing if he’d been wounded until a man whose head was lying on his leg was given the coup de grâce and the bullet after doing its job hit him in the leg wounding him slightly.

The Germans covered the victims, many of whom were still moaning, in brushwood and hay and set fire to it. When the flames reached Hébras, he managed to exit the barn and enter a yard where he encountered four of his friends, two of whom were also wounded. After breaking a hole through a wall the lads took refuge in another barn but were forced to leave this and hide in rabbit hutches when a soldier set light to the straw and fired incendiary bullets that set the roof on fire.

Only one woman, Madame Rouffanche came out of the church alive and she describes how at around 16:00 two young soldiers had carried a box into the church ‘from which hung strings that trailed on the ground.’ When these ‘strings’ were lit the box exploded giving off thick, black, suffocating smoke. The women and children packed into the church panicked and ran to areas where they could still breathe and the crush of bodies broke down the door of the sacristy. The Germans shot down all who sought refuge there and it was here that Mme Rouffanche’s daughter was killed by a bullet fired from outside the church. More shots were fired into the church, hand grenades were thrown in and then straw, firewood and chairs were piled on top of the bodies and set on fire. Hidden by the smoke, Mme Rouffanche hid behind the altar and then using a stool climbed out through the middle window. She was followed by another woman carrying a baby but the baby’s cries alerted the Germans and she and her child were both shot and killed. Mme Rouffanche crawled to a nearby garden where she hid until she was rescued at 17:00 the following day. The youngest child murdered in the church was only one week old.

A tram that arrived on test from Limoges was stopped and searched and its driver was shot and his body thrown into the river. The other engineer was told to return the tram to Limoges but it is odd that he did not stop a later scheduled tram from making the journey to Oradour.

17:00 Saturday 10 June 1944

With the bulk of the killing completed, the SS now turned their attention to ‘mopping up’ any survivors. An elderly bedridden man was burned to death in his bed; a group of cyclists from Limoges was shot near the smithy; bodies were found down the well near the modern Memorial Centre and people from outside the village who came to look for their children were also killed.

Sometime around now Diekmann reported in person to his commanding officer Sylvester Stadler back in Limoges. Stadler was visibly shaken by what had been done and told Diekmann that he would be court martialed as a result of his actions.

18:00 Saturday 10 June 1944

With the church now burning fiercely, the troops began looting and setting fire to the remaining houses in the village and as their homes burned, a trickle of people who had been hiding began to make their way across the fields to safety.

19:00 Saturday 10 June 1944

When the scheduled Limoges to St Junien tram arrived it was boarded by the SS who checked the passengers’ papers separating the men from the woman and taking them to the German command post where, expecting to be shot, they were released and told to go. One woman was even given a bicycle by a soldier as she lived some distance from the village. It is possible that by this time Diekmann had returned after his dressing down by Stadler with his appetite for killing diminished.

Sunday 11 June 1944

At around 11:00 the last of the SS left Oradour with their booty and local people began to make their way into the village to search for their relatives. A man who was looking for his sons near the church heard a woman crying out, ‘I am suffering too much. Carry me to the river, I want to die!’

Catching sight of her the man said, “I did not know there was a Negress living in Oradour!” It was Mme Rouffanche who was extensively smoke blackened and found to have been shot four times in the legs and once in the shoulder. She was taken to hospital in Limoges where she was to spend a year under treatment for her physical and mental wounds.

Monday 12 June to Thursday 29 June 1944

The SS returned to Oradour on Monday morning and made what could only have been a futile attempt to clear up the mess. A burial party dug two main mass grave pits and other corpses were buried individually around the village. On Tuesday, the Germans abandoned their clear-up attempt and left Oradour never to return.

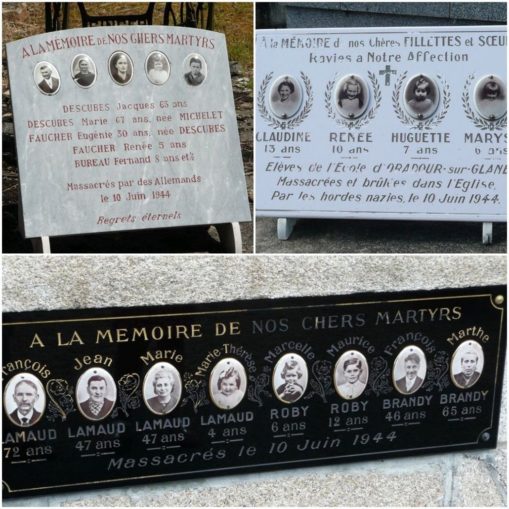

The survivors of the atrocity now had the appalling task of recovering and identifying the remains that by now were decomposing in the hot summer sun. Out of 642 victims, only 52 bodies could be identified with the remainder simply being listed as ‘officially declared missing’ in accordance with French law.

On 29 June, Adolf Diekmann left his command post shelter north of Noyers during a bombardment without wearing his helmet and was, rather conveniently one might think, hit in the head by a shell splinter. He died instantly.

With Diekmann’s death the Oradour affair was forgotten about by the German High Command and no one was ever tried or punished for their involvement in the massacre.

The Bordeaux trial, February 1953

Eight and a half years after the massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane, the French government tried all those members of the 3rd Company of the 1st Battalion of Der Führer Regiment of Das Reich 2nd SS-Panzer Division that were still alive and could be brought before the court. The Commanding Officer, General Heinrich Lammerding who had ordered the hangings at Tulle and almost certainly the massacre at Oradour could not be persuaded to attend. He sent a sworn affidavit to the court.

The trial under presiding judge Marcel Nussy-Saint-Saëns (nephew of the famous composer) was complicated for a number of reasons. Only eight German nationals were present as the 13 conscripts from Alsace (referred to as ‘malgré-nous’ or ‘against our will’) and one SS volunteer were French nationals some of whom had been minors at the time of the massacre and who, it was argued, could therefore not be held accountable for their actions. There were calls for the German and the French defendants to be tried separately.

The majority of those packed into the tiny courthouse were members of the press and back in Germany the Deutsche Zukunft (German Future) newspaper went so far as to suggest that it was unfair for the British government to reward Air Marshal ‘Bomber’ Harris, whom they held responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians in Dresden, with a peerage yet treat the deaths of 642 people in Oradour as a crime.

After a bad-tempered trial only two German defendants were sentenced to death and the remainder to between eight and ten years in prison. This caused outrage in Alsace where the verdicts were thought to be too harsh and in the Limousin where they were considered to be too lenient.

On 19 February, the French Assembly passed an amnesty bill for former French citizens conscripted into the German army upon which the widespread protests in Alsace ended and three days after the bill was passed the 13 conscripts were released. The two German nationals condemned to death, Lenz and Boos, were both eventually pardoned and all the defendants were released by 1958.

The aftermath

When General de Gaulle visited Oradour he decided that the ruined village should be preserved so that future generations should not forget and also that a new Oradour should arise alongside the ruins. When the convicted defendants were released on amnesty, the mayor of the new Oradour returned the Croix de Guerre that had been awarded to the village and broke off all relations with the state, a dispute that was to last for 17 years. The villagers also refused to place the ashes of the victims in the state memorial which later was to become a museum and visitor centre.

Why did the massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane take place?

The simple answer is that nobody knows. There are two theories that seem plausible. The first is that when Gehrlach and his driver were abducted, they were taken to the village of Oradour-sur-Veyres which did have active Resistance units and he simply confused the names of the two villages reporting back after his escape that he had been taken to Oradour-sur-Glane. On the evidence though it is more likely that the Germans had been taken to Peyrilhac but in their confused and frightened state they may have simply seen a signpost to Oradour-sur-Glane and thought they were in that location.

This theory doesn’t stand up to examination though as when Diekmann’s convoy approached Oradour-sur-Glane they did so from one direction only. They drove straight to the village centre and then in a casual atmosphere, as attested by eye-witnesses, deployed foot patrols to secure the roads out of the village. This would have been suicidal against determined Resistance opposition and an experienced officer like Diekmann would have first surrounded the village with an overwhelming show of force before mounting his attack.

The second explanation is that the SS, facing a perilous trip to Normandy with Resistance guerrilla ambushes likely along the way, simply wanted to carry out an atrocity against a soft target to teach the Resistance a lesson that would deter them from making such future attacks. If this was the intention it certainly worked as the column met no further resistance on its journey north but it doesn’t explain why Diekmann’s superior was so appalled by his actions when he reported back to him in Limoges that he threatened him with a court martial.

I think we simply have to accept that we will never know the true motivation for this hideous war crime. Could the real explanation be that it was simply due to an excess of zeal on the part of one fanatical Nazi officer who wanted to avenge Helmut Kämpfe’s assassination by the Resistance? It’s as likely an explanation as any.

What happened to those in command at the time?

SS Oberstgruppenführer Heinrich Lammerding had already been condemned to death in his absence for the hangings at Tulle so it is not surprising that he did not attend the 1953 Bordeaux trial. He hid for a short while in Schleswig-Holstein before returning to his home town of Düsseldorf where he lived quite openly and undisturbed as the head of a thriving business until his death in 1971.

SS Standartenführer Sylvester Stadler was (conveniently?) promoted out of Der Führer on 14 June 1944 before any investigation into Diekmann’s actions could take place. He was never tried for any war crimes and died in 1995.

SS Sturmbannführer Adolf Diekmann was killed in action shortly after the massacre.

SS Hauptsturmführer Otto Erich Kahn lived quietly under his own name in Germany and died in 1977.

SS Untersturmführer Heinz Barth lived openly under his own name in East Germany. In 1983 in a politically motivated trial he was sentenced to life imprisonment showing no regrets for his actions. In 1997 Barth was released from prison on grounds of ill health upon the reunification of Germany. He was the most senior person involved to be tried for involvement in the murders. He subsequently successfully appealed against a ruling that had denied him his war pension.

Visiting Oradour-sur-Glane

The village is situated approximately 15 miles to the west of Limoges on the D9 which is off the N140. Parking and admission to the ruins are both free but dogs other than guide dogs are not admitted. Visitors may enter the church but there is no access to any of the other buildings for reasons of health and safety. Photography is allowed everywhere but in the Memorial Centre itself. When the Centre is closed, the ruins may still be entered via gates at each end of the village.

References:

Oradour-sur-Glane, The Tragedy Hour by Hour, (2001) Hébras, Robert, Saintes, Les Chemins de la Mémoire

Website: https://www.oradour.info/index.htm (Michael Williams)

© text & images Tom Pudding 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player