March 6th, 1807.

George is off to Italy, where I am sure he will have a capital time ogling churches and whores, and buying paintings that might be by Salvator Rosa but are probably not.

I have made the Grand Tour; it is something that every young bear or man should do once, but only once. There was a bear in Florence – but I digress.

He has left me in the care of his manservant Jem Voakes, a good fellow and we are easy together. Jem is out of countenance because his lordship has not seen fit to pay him for three months, but he does not yet see the need to ‘mizzle’, as he puts it.

We went to a dogfight. I dislike these human pastimes. If I need to fight I will, but it is not an entertainment. Jem bet on the wrong dog and lost £2. He was mightily displeased.

Jem plays the flute well enough, and I indicated to him that he should strike up a tune. I danced – I cannot say that I did it well, as I am out of form and my old joints are stiff, but it was good enough for a dogfight crowd. We took requests for popular tunes, and made £8 2s 4¼d, though that last farthing was a brass one. Jem was much cheered and said I was a ‘diamond bear’.

We went to the inn and drank porter. The owner of the losing dog was there, and the poor creature was in a bad way and not long for this world. I looked at the owner, and he took my meaning and nodded. I carried the dog outside, finished him quickly and ate most of him – he was a big dog and I had to leave the foxes their portion. We bears understand simple folk better than we do the pampered nobles.

June 25th, 1807.

George has returned from his travels. I was glad to see him, but I must admit that I have enjoyed my time with Jem and his cronies more than watching him mollock with doxies and catamites in his chambers while I pen his essays on Aristotle and Plato. He has published his poems under the title of Hours of Idleness, and I must admit that it is a fitting title. The book contains many of the ‘Fugitive Pieces’ that he circulated among his friends, but he has omitted some of the more salacious odes and put in some new works. I cannot but think that those he removed were better and truer than the dull stuff he added.

The reviewers have not been kind, and he is downcast. We went for a ramble to Grantchester and both got royally drunk on the strong ale they serve at the Green Man. As we staggered back to Cambridge I happened on a badger, which I ate to George’s amusement. I offered him some, but humans are oddly squeamish about such things. Notwithstanding that, he is happier now and inclined to accept his misfortunes philosophically, though I think he will have a sore head in the morning.

Octr. 16th, 1806.

George has a new friend by the name of John Hobhouse, whom he refers to as ‘Hobby’. To his other cronies he describes their relations as ‘pure’. I have reason to think otherwise, but let it pass.

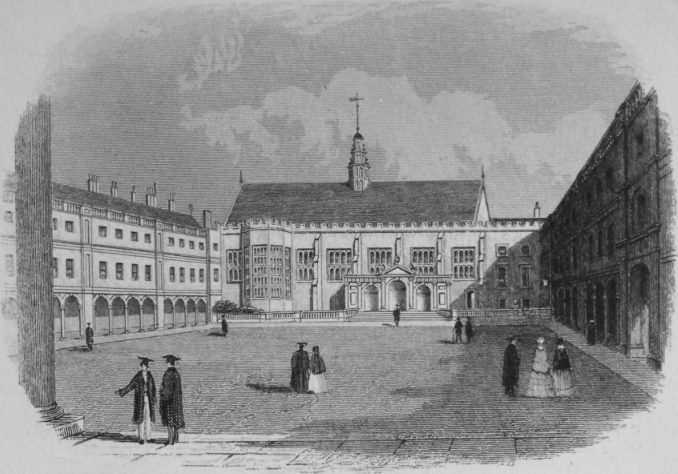

Meanwhile my time is more than occupied by writing essays on Homer and Hesiod, Sallust and Suetonius. To this end I have often visited the library attached to the college, a noble building designed by Sir Christopher Wren. I had some trepidation about gaining entry to this hallowed place, but I found that all that was necessary was to wear George’s academic gown. The aged and purblind don who presides over the library is so eager to ensure that all entrants are properly attired that he is quite oblivious of their species, and I can wander among the deliciously musty bookcases to my heart’s content.

Decr. 19th, 1806.

I am concerned about George. Last night he lost £60 and a gold ring at faro. He has been playing deeper and deeper to recoup his losses, but he has never had either skill or luck at the tables. When he arrived in Cambridge with an income of £500 a year, it seemed that this was more than sufficient for a young nobleman to live handsomely, but he has squandered it in dissolute living. Two wine merchants and three tailors have already refused to extend any further credit to him, and I have noticed that the trollops he brings to his rooms are coarser than before. This morning he lit the fire with his bootmaker’s bill, which was not a small one as he has special boots made to conceal the deformity of his right foot.

So far his charm has carried him through, but I am fearful of what the future may bring.

April 20th, 1808.

George’s final examinations are rapidly approaching. He has done no work whatever, and has merely spent the time roistering with his friends and sundry loose women and looser boys. It is clear that he is in no state to attend these crucial trials, and that I shall have to impersonate him. My experience at the library suggests that I shall be able to carry it off.

Jem will ensure that he is plied with sufficient drink on the eve of each paper to prevent him from rising before noon, and will lock the door of his rooms to prevent him from wandering about during the hours set for each paper. What he does during the evening is of no importance, though the other students will be spending long and anxious candlelit hours revising their knowledge. I have no need of this: I have not wasted the last three years. (Well, not much of them – George and Jem and I have had many a roaring time, of which I have fond memories.)

May 4th, 1808.

The examinations have begun. I was much amused by the ease with which I was able to take my lord Byron’s desk, merely by donning the required garb. It is true that the dons have not seen much of him during his residence at Trinity.

Nevertheless, it is a punishing time. There are two papers of three hours every day. My paw aches from having to grasp a quill designed for human hands for so long, and my mental powers are on the verge of exhaustion. Today I had to write a Latin version of Gray’s Elegy in hexameter metre, and I flatter myself that I did not give a bad account of it, though my rustic Latin is a long way down the stream of time from the pure source of Virgil:

Vespertina notat finem campana diei,

pigra armenta boant, tarde tenduntque per agros;

passibus erga domum lassis se vertit arator,

et totas terras tenebrisque mihique relinquit.

I will not trouble you with the rest of my attempt. I must admit that I would rather dance in chains for a fortnight than undergo this protracted inquisition, but I feel kindly towards George, who may be an idle fellow but has treated me well, and I will do my best to help him.

May 10th, 1808.

I was delighted to see that one of the questions was on Tacitus’ account of the defeat of Boudicca (or Boadicea if you will, but that name is from a corrupt medieval manuscript), a topic perhaps not unexpected in an examination set by an English university. Some years ago I danced in the Bullring in Birmingham, and between performances Fred and I rambled around the outer reaches of this sooty town. No one knows where the final battle took place, except that it was a long way from the homeland of Boudicca’s tribe, the Iceni, in Norfolk. Our wanderings took us south to Stirchley, a humble village near King’s Norton whose main street, straight as an arrow, gives a clear indication that the Romans were here, and indeed it was the main road between Letocetum (now Well) and Salinae (now Droitwich).

The road runs at a slight elevation above the banks of the Rea, a small but ill-tempered river which, when swollen by rain, often floods an extensive area of the valley, which at other times is a treacherous marsh. A bare two miles to the north, in the even more miserable village of Metchley, lie the remains of a Roman military encampment. We observed (or it would be fairer to say that I observed, as Fred is no historian) that there is another road that runs parallel to the Roman one behind the crest of the low hills to the east of the valley, and along which a whole legion could pass unobserved from below, then suddenly descend into the valley and annihilate an ill-armed band whose war chariots were bogged down in the marsh, as Tacitus suggests.

This is only a fancy of mine, but it is a topic to win the attention of an examiner, and I hope it has had that effect.

May 20th, 1808.

I sat the last paper this afternoon, and am very happy to write that the imposture has been a complete success. Not an eyebrow has been raised as I entered and left the examination room, draped in my voluminous gown. George, who I must admit was, as usual, pretty far gone on inferior port by this time of day, embraced me tearfully and said that I was a bear beyond compare, and he would write a heroic ode to me in the style of Pindar. ‘In English, of course,’ he hastily added. I do not think the Greek ode I wrote in the examination was very good, but George could not have composed the first line.

We celebrated my achievement at a local alehouse. I had to carry George home, not for the first time. The faithful Jem helped me to put him to bed.

Now we shall have to wait a fortnight for the results to be posted.

June 2nd, 1808.

I have won a First! – or properly I should say that George has got it, and his name is on the list which was posted on the noticeboard this afternoon. Yet we know who laboured for it, and the honour is mine. Unknown to the world at large I am a Bachelor of Arts, a strange distinction for a matron, not to mention a bear.

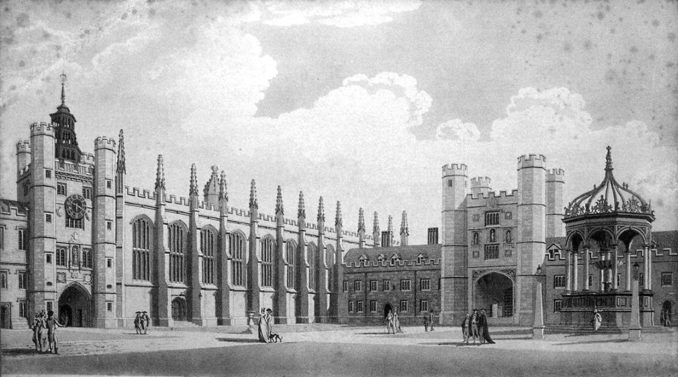

George and Jem were as delighted as I, and we danced around Great Court until my acute eye detected a proctor emerging from the gatehouse. Luckily we were in the opposite corner and were able to leave by the screens passage past the entrance to the Hall and into Nevile’s Court, and across the river to the Backs. From thence, of course, it seemed natural to continue to an inn, where we toasted our success in what the landlord described as claret. After a dinner of tolerable roast mutton we continued our celebrations until long after midnight, the hour when the college gate is locked.

There is a fairly easy climb in over a wall to the left of the gate, with a tree growing conveniently near to aid the ascent. Nevertheless, it was only with some effort that we were able to haul up an inert George, with Jem pulling from the top of the wall and me pushing from below. The street was still loud with undergraduates shouting of their success or bewailing their failure, and we were reached George’s rooms without incident.

When he was snoring stertorously in his bed, Jem said to me, ‘Daisy, there’s summat I needs to tell yer. Yer done right by George, and I done right by ’im, an’ ’e’s well settled now. But ’e ain’t paid me for more ’n a year, and I’m considerin’ movin’ on. An’ I don’t see what ’e’ll do wiv yer when ’e comes down from university, an’ that’s not long now.

‘But I got a plan. Like ’is lordship says, yer a bear o’ great brain, and I think you an’ me’s got a future together. I was thinkin’, we could set up a dancin’ school for bears, take in young cubs an’ train ’em up an’ send ’em out to earn a good livin’ like yer done yerself. I even thought o’ a name for it, The Bear Necessities. Think about it, Daisy me gal. There’s no ’urry for a while. We got to get George presentable-like in the mornin’ anyways.’

June 3rd, 1808.

After a sleepless night in my room in the tower, not aided by the consequences of the execrable wine, I have decided that Jem’s plan is a sound one. We have guided George along his stormy course for long enough. He is a published poet, for what that is worth, and it is time that he stood on his own two feet, twisted as they may be.

We leave tonight. There will be no farewells. But I shall put this journal on George’s desk, and perhaps he will understand our reasons for departure, though more likely he will not. I wish him every success.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2018

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file